I’m reading a lot at the moment – so forgive me if the next few posts are based on thoughts solely derived from the last book I’ve read.

I’ve just finished Jonah Sachs ‘Unsafe Thinking’. If you recognise the name, Sachs is the author of Winning the Story Wars, which is a brilliant read on using the power of stories to engage people to take action.

But in his latest book, he explores how we can get out of the patterns of behaviour that find ourselves following a well-trodden path in our approach to solving creative campaign problems.

I’ve come away from reading it with 8 principles to push when trying to come up with next campaign approaches and tactics.

1 – Push imagination – ’never use the same tactic twice’ is the advice from Micah White, who wrote the Adbusters manifesto that helped to launch the Occupy Movement. He contends that novelty and unexpectedness keep the public and press interested in a campaign – imagine approaching a campaign planning session where you couldn’t reuse an approach that had worked for you in the past.

2 – Push your passion – research shows that the most effective thinking can come when you’re ‘in the flow’ – when you’re working on something that you’re truly passionate about. Work to solve problems that you really believe in.

3 – Push out of the ‘expert trap’ – If you’ve ever been in a situation where you’ve been coming up with you’ll be familiar with the idea of ‘paralysis of analysis’. When you’re so much of an expert you can’t see the solution. A little knowledge about something is vital, too much and you can get entrapped, unable to see signals and information that might be telling you something different. Experts don’t always know best!

4 – Push those on the edge of the room – Sometimes we can be too close to a situation to be able to assess the best options. We find ourselves frozen by the urgency of solving a problem. Those on the outside of a room – close enough to the details but with a different perspective can be helpful.

5 – Push intelligent disobedience – some of the best solutions come from those who have a hunch that is just outside the boundaries of what’s acceptable. How can you encourage others to explore these space – it’s a tightrope to walk but this discomfort can lead to reasonable risk-taking that can lead to new approaches or innovation.

6 – Push (friendly) conflict – employ a ‘red team’ who are specifically mandated to challenge a strategy to make it stronger. It’s worked as an approach in the armed forces for decades, where everyone knows the purpose of the team is to expose flaws so they can win.

7 – Push others forward – If you’re a leader and you start a meeting sharing your opinion, chances are it could be a quick meeting, as others will often decide to agree with you. Instead stand back and encourage others to share – ask them to discuss what the group doesn’t already know. It’ll bring new thinking into your planning.

8 – Push dialogue with those you disagree with – a harder approach when campaigning is so often about identifying how to, but dialogue with those who hold opposing views can help to build new understanding and challenge blind spots in our own thinking. So often our approaches are tied to our beliefs and values – some dialogue might help to shift that.

Some of these approaches feel easier to push into than others – I can see how it’s possible to push (friendly) conflict, how you can change your management approach to push others forward or pushing imagination. While others feel harder, like dialoguing with those you disagree, but as Sachs writes in the book – pushing into the discomfort is a key element of identifying the ‘unsafe’ approach is working.

Category: learning

What will campaigning be like in 2040?

In 2010, NCVO produced a useful resource asking what campaigning might look like in 2015, it’s worth a read as it accurately predicts some of the trends that we’re seeing today. I’m also a big fan of this resource from Mobilisation Lab looking at some of the trends that campaigners will face in 2018.

But what would happen if we looked way further ahead – to say 2040 – what might campaigning look like then?

I had the opportunity to spend some time with the School of International Futures (SoIF), using some of the tools and techniques they use to work with to ask what the future might be for campaigning.

One of the things I was most struck with from the session was the sense that you have to look at the margins for ideas of what might become the future, that the further reaches of literature, the arts and academia to get a glimpse at what might become a future reality.

SoIF took us through a range of exercises to get us thinking about what might be ahead in the future – here are 5 scenarios that I’ve sketched out from that conversation;

- Apptivism – we’ll see an end to campaigning informed by altruistic motives of standing up, and instead, campaign actions will be driven by more intrinsic motives – where we’ll get rewarded by companies or other groups for taking action. We already see the rise of the role of Uber, Airbnb and others who are turning their customers into activists – and with the vast amount of data they hold, presumably offering incentives, like free rides, for those who take action on their behalf. Beyond that, some have suggested that Blockchain could provide a tool to help to register participation in campaign events or activities, which could then be rewarded.

- Algorithmocracy – the power of computers will be able to crunch so much data that we’ll no longer need decisions to be made by a form of representative democracy, but instead from publically held data points – what you say on Facebook (or whatever has replaced Facebook) will define the decisions that are made. As author Eli Pariser writes in The Filter Bubble we could be looking at “a world constructed from the familiar is a world in which there’s nothing to learn, since there is invisible autopropaganda, indoctrinating us with our own ideas”. As the stories around the Cambridge Analytica have shown in the last few weeks there is a huge amount of power in who holds data and information so perhaps our future campaign targets will be companies like Facebook rather than Governments.

- Return to MySpace – a reaction against the influence of social media platforms like Twitter and Facebook means groups will head back to digital infrastructure that was previously considered obsolete is taken over again with individuals finding online tribes in different spaces – it’s a trend that’s already been observed by some as alt-right groups have taken over MySpace. but also in how more and more messenger apps like WhatsApp are being used to bring groups together.

- VR Organising – at the heart of organising approaches is about bringing people with a common interest together to build their power, but does the arrival of virtual reality mean that this will no longer have to happen in a physical location – instead you’ll be able to do it from the comfort of your front room but feel like you’re in the same room as others who you’re going to take action with.

- Gathering together – we’ll see a focus on in-person methods to bring people together, as people reject the role of technology and want deeper connection. Everyone has long suggested that death of offline approaches, but the success of big organising approaches in insurgent campaigns like Bernie Sanders suggest that people still have a thirst for coming together to secure change, and work by my friend Casper terKeile suggests that the thirst for a community to make meaning of the world is growing not decreasing.

But as I reflect more on these scenarios, I’m also struck that the fundamentals of campaigning probably won’t change – the role of campaigners will still be about building power and mobilising – so perhaps a more important conversation to have is what’s the future direction of power. Not just the visible power, but also who has invisible power and influence?

Re-energise your campaign – lesson from #BondConf session

I was really fortunate today to host a panel at the Bond Conference on how to ‘re-energise your campaign’. It was a great hour-long discussion between four inspiring campaigners, who are all leading really important campaigns with some new and different approaches.

It was one of those hours where I was trying to keep time, capture learnings and facilitate a discussion – needless to say I failed to time keep well, but a few lessons I took from the conversation;

- Build a simple structure that works for volunteer – Robyn, one of the co-directors of IC Change, which has achieved remarkable success, reminded us that we need to build structures for our campaigns that work for volunteers and not the other way around. IC Change was a built on a range of volunteer roles, some long-term, some surge roles to help at busy times, and others to utilise specialist skills or knowledge.

- Be intentional about building relationships – at the heart of IC Change is a core team of volunteers who are working together. They’re committed to spending time building real relationships with each other. In our campaigns we need to put in the time to help people get to know each other – echoes here of the work of Hahrie Han in building social ties over meals and other social activities.

- Just do something – Trica from Sum of Us shared how they often launch a campaign without having a fully agreed strategy, but they want to get a sense of how the corporate will react so put out petitions – sometimes with remarkable success rather than spend months developing the strategy. It was a theme that Robyn also picked up on that IC Change has because it volunteer-run looked to launch minimum viable proposition campaigns. There was something refreshing and exciting about just doing it!

- Find the pressure point – Sum of Us is about looking to find the most appropriate pressure point of their target, whats going to get them to move and respond to you. Then they design out the approach to take informed by that. Find the tactic that works to move your target. Keep experimenting if you’re original approach doesn’t work. Loads more about the approach of Sum of Us here.

- Build diverse and resilient coalitions – a theme across all the presentations was the importance of always looking to work with others, and while that can come with challenges working together helps campaigns to draw on each other’s strengths. For example, Rebecca from Ben + Jerry’s talked about how working with IRC meant they had access to policy knowledge and expertise. It’s about knowing what you know and what you don’t know.

- Be flexible – Larissa from Youth for Change reflected on how her campaigning had worked because they’d be flexible at adapting to where they were being successful, and look to go where people are to have the conversations. That could be a Whats App group, a Slack channel or something. Being too prescriptive can easily take valuable energy away.

- Get out and about – So Ben + Jerry’s have an advantage here as they have an Ice Cream Van, but Rebecca shared how important getting out and about to go to where people gather to have conversations about our issues. The Homecoming Tour, for example, was about going to communities and having conversations about welcoming refugees, and it was a great chance to have deeper conversations. Going offline helped to ground the campaign in realities that couldn’t be understood in a London planning meeting.

- Live your values – If as, Sum of Us is, you are asking your targets to live up to higher practices and values, you need to live those out. We had an important discussion about how we make sure that more diverse voices are heard in our campaigning. If our values don’t align with the work we’re doing we’re always going to be drawing energy away from our mission.

- Eat together – Perhaps an unintended theme throughout the presentations was the role of food at the heart of campaigning, from campaign planning over a cup of tea, to bring snacks to a meeting, to ice cream, everyone seemed to agree on the importance of food!

- Don’t forget the ‘why’ – a powerful reminder from Larissa that we all come into the work of campaigning because we want to change things, and if we’re feeling like our campaigns are lacking the energy they need, sometimes we need to go back to the ‘why’ we do this work and rediscover the passion that brought us to it.

If you joined the session at #BondConf I’d love to know what you’re reflections from the conversation was.

Where could good campaign ideas come from?

Steven Johnson asks a simple question – where do good ideas come from? Looking across the history of innovation and the development of some of the most important breakthroughs in history, his book by the same name explores what are the lessons that we can learn from them, and apply in our own work.

The themes of the book really resonated with me. As a campaigner, I’m constantly on the lookout for the latest idea and approach that will help my campaign to gain the traction needed to secure change.

A campaigners work is often about doing the most with the scarce resources that exist so any edge we can get needs to be explored.

So what are simple steps that we can take as campaigners to come up with better ideas?

1 – Go for a walk – Getting away from our desks is one of the simplest actions you can take. It draws you away from the every day tasks that you get focused on when sitting at your desk. It gives your mind space to make connections between ideas you’d previously had. Try it. I know that I often find some of the best campaign ideas I have come to me on my cycle ride to and from work – which then presents the challenge of how to remember them before I get into the office.

2 – Read a newspaper – in the days of social media we get specific and curated information in front of us, but we’re losing out by not reading a newspaper where you browse across articles on a range of subjects, some of which might peak our curiosity, even those not linked to a topic we might naturally be interested in. Johnson is also a big advocate of reading more in general, he points to the examples of innovators like Bill Gates who take a whole week out a year to read – now most of us can’t devote that much time to reading, but we can all increase the breadth of the content we’re reading.

3 – Chronicle everything – During the Enlightenment, keeping a ‘Commonplace Book’ was well common place! These book are collections for ideas, quotes, anecdotes, observations and information you come across, and help you to review them to make connections or new ideas. Johnson encourages us to create our own 21st century version of these books, a collection of quotes, ideas, thoughts but through a digital medium. More on how to create them here.

4 – Connect with others in coffee shops – Johnson is an advocate of the inhabiting spaces where you’ll find ‘liquid networks’ – groups of people working on different challenges and topics. In those space he argues that ‘different people with different perspectives coming together’. The 21st coffee house might be very different from those from a few hundred years ago, but the principle of proactively taking time to meet with, learn from and debate with those working on very different challenges from yours seems to me to be a good one. One practical way I’ve thought about doing this is looking to go along to talks and conferences on topics that aren’t immediately related to what I’m working on.

5 – Make a mistake – that might sound counter intuitive but Johnson argues that ‘being right keeps you in your place, being wrong forces you to explore’. Some of the most important innovations come about because of mistakes. For me this is about how we continue to embrace a culture that allows us to interrogate the mistakes we make, rather than looking to hide them or not make them for fear that in some way we’ll be penalised. It’s a theme I’ve explored more here.

6 – Take up a hobby – Individuals like Benjamin Franklin, the American inventor, or John Snow who is seen as the father of modern epidemiology, because of his work in tracing the source of a cholera outbreak in London, have a number of things in common, including the fact that they both had lots of hobbies. In an era when we’re told to focus our efforts on one thing, Johnson argues that having hobbies can be an invaluable way in helping our minds to make new connections, and to bring the approach we might take from on hobby into thinking about another area of our work.

7 – Have lunch together with colleagues – Psychologist, Kevin Dunbar set up cameras in a biology lab and look to study where most of the research breakthroughs came from. Now you might expect it’d be at the scientist’s desk, but it turned out to be a conference table in the middle of the room during breaks. Dunbar suggests that this was because it was the space where researchers could challenge assumptions or blend together ideas or hunches they were having. So while we might think we’re doing our best work at our desks, sometimes the questions that we need to be asking across the table from colleagues during a coffee break or lunch.

If you want to learn more about Johnson book I’d recommend this and this. He’s also done an excellent TED Talk on the themes in his book.

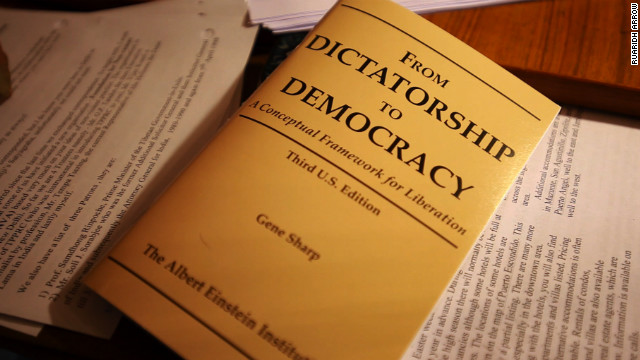

The legacy of Gene Sharp – some tools for campaigners

It was announced last week that Gene Sharp has passed away. If you’ve never come across the work of Sharp you should. He was one of the most important writers, thinkers and strategist on nonviolent resistance. Tim Gee has written this really nice reflection on his work and legacy.

The short pamphlet that he is most well known for is ‘From Dictatorship to Democracy’ which was translated into over 40 language, and part of his many writing that influenced numerous movements around the world, including those like CANVAS in Serbia who overthrew Slobodan Milošević, many of those involved in the Arab Spring movements and many many more.

But there is a richness in his work that’s applicable for any campaigner, so I wanted to share some of three tools that Sharp developed or inspired that I’ve found especially useful to consider in campaign strategy.

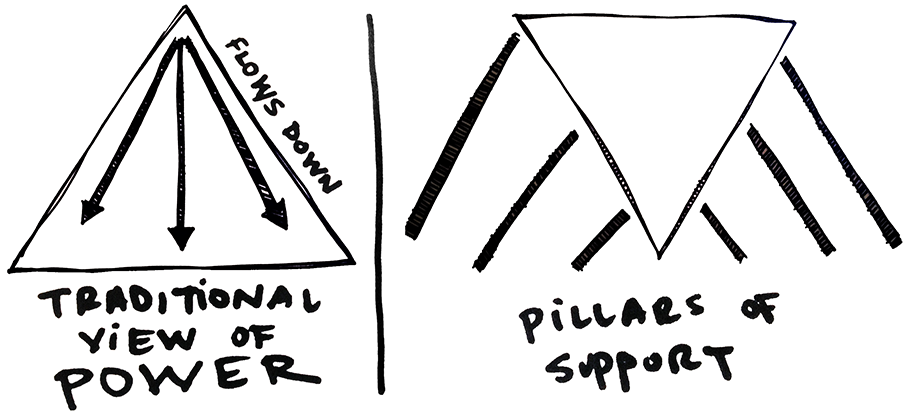

1. Pillars of Support – Traditional power is thought of as a pyramid, where power flows from the top downward, but Sharp suggested that as activists we should turn the pyramid upside down, and see that power is ultimately dependent on the cooperation and obedience of large numbers of people acting through the institutions that constitute the state. These are its pillars of support.

Those pillars can include institutions like the military and judiciary, but also media, education system and religious institutions which can support the system through their influence over culture and popular opinion. Sharp suggested that activists should focus on a target’s pillars of support, and then set about working to win over, or at least neutralize, those pillars of support so that the foundation that sustains the target begins to crumble

This is a brilliant case study of how the model can be applied to the movement for equal marriage. See more on this approach here and here. Too often I think campaigners focus on changing the position of the government, but Pillars of Support reminds me that sometimes looking beyond that can lead to impact.

2. 198 Methods of Nonviolent Action – The most comprehensive list I’ve ever come across of the “entire arsenal of nonviolent weapons” at the disposal of change makers.

Sharp listed almost 200 different approaches and classified into three broad categories: nonviolent protest and persuasion, noncooperation (social, economic, and political), and nonviolent intervention. If you’re ever looking for campaign tactic inspiration this is a great place to start.

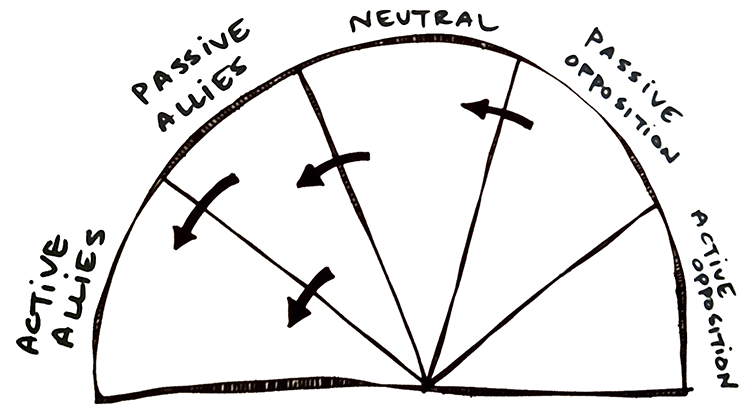

3. Spectrum of Allies – In campaign strategy we can too easily focus on those who are already supportive or those who are opponents, and so our campaigns are planned in a very binary manner. The Spectrum of Allies recognises that often many groups are in the middle, or those whose support or opposition is softer than it might appear.

The goal of the spectrum of allies is to identify different people—or specific groups of people—in each category, then design actions and tactics to move them one wedge to the left. Once you’ve identified where different groups sit then you can start to think about how you can engage them in your campaign. See more on this approach here and here.

A (comprehensive) list of training for UK based campaigners

There are lots of ways to learn how to be a great campaigner – but some people find that going along to a formal training or conference as a useful way to pick up new skills, dive into understanding strategy or make more connections.

I was asked by some colleagues at work to put together a list of training opportunities for those working in campaigning here in the UK – and came up with the list below. The comments are based on my experience attending or what others who’ve gone along have told me.

It’s as comprehensive as I can make it, but I’m sure it has got gaps in it, so please do use the comments below to suggest other training, or update on the information I’ve provided. I’ll try to keep updated.

If you’re not someone who enjoys training I’ve made some suggestions here of what else you can do, and a list of some great campaign reads here.

For full disclosure, I helped to found Campaign Bootcamp (and still serve on the board), worked at Bond when they designed the latest training content and have spoken on the NCVO Certificate in Campaigning.

Conversations for campaigners in 2018

After the last few years we’ve had, it seems foolish to make any predictions about what might happen in 2018. So as we start a new year for campaigning, I’ve decided not to make some predictions, but as I head back to work for the new yearm to make some suggestions of conversations that I hope we can have to make us more effective campaigners in the next 12 months.

1 – Are the tactics we’re using working? The end of the email your MP actions have long been predicted, with MPs repeatedly telling us that they don’ find them effective, and others using software to filter them out before they land in their inboxes. As the Social Change Agency have written recently ‘digital campaigning can feel a little stale’, while organisations like 38 Degrees are also looking to overhaul their tools that let you contact your MP. But as a few innovate out of the problem, the declining impact of these approaches impacts us all so I hope we can have a conversation about how we use digital tools to maximise their impact.

2 – Ask each other why aren’t we winning – Call me old-fashioned, but for me campaigning is about winning change. It means that I can get frustrated when I get a request to join a campaign where I can’t see how my action will contribute to the desired change. At the heart of good campaigning is a clear theory of change, which has had the assumptions challenged and stretched before a path of action is reached. With limited resources, we need robust theories of change to win, so in 2018 I hope we can go back to resources like Pathways for Change to make sure we’re asking difficult questions when we’re not winning.

3 – What does the changing media landscape mean for our campaigning? Nine of the top 20 news articles shared during the election were from non-traditional outlets, while a story on animal sentience became the most viral politics article of 2017, and was started on a small agricultural news website. More and more people are getting their news from hyper partisan sites, with content designed to be shared on social media, and with Facebook. If campaigning is about shaping a news agenda, how do we do that in what feels like an increasingly polarised and fragmented media landscape?

4 – Can we do more to share what’s working? I was really excited to see 38 Degrees publish a comprehensive study into their turnout campaigning they’d done around the General Election, and Engaging Networks have shared some useful benchmarks, and this is great by Forward Action. All examples of people sharing what’s working without needing to. But it feels like there is so much we could be doing, and in a more comprehensive way. I’m a member of the US based Analyst Institute which looks to share academic and practioner studies about what’s working, but that’s very focused on American electoral politics. So how do we encourage more of this among campaigners, including making our evaluations, including the not so good parts, more accessible and available to others?

5 – How to take GDPR seriously, but not become overwhelmed by it – As I wrote back in the summer, GDRP is coming and it’s something we do need to take seriously. Given the battering, the reputation of many charities have taken over the last few years, but I’m concerned that many of us will end up being paralysed by the regulation, some of the questions I’ve seen circulating on the ECF list indicate a nervousness about it. How do we make sure that we’re following the regulations, but also not further using this to hamper our effectiveness to campaign and mobilise our supporters who want to be engaged in our campaigns.

Help! I've got a new campaigning job, what should I do?

It’s a year since I started my role leading the Mobilisation Team at Save the Children UK, and over the last 12 months I’ve asked by others for advice about how to transition into well into a new campaigning job.

So I thought it might be useful to share a few reflections and lessons from what’s been a really exciting, varied and interesting 12 months, in the hope they might be useful for others moving into new advocacy and campaigning roles.

1 – Start by listening and then listening some more – The most useful book that I’ve found for thinking about the transition into a new role is ‘The First 90 Days’ by Michael Watkins. While the book is certainly focused on those making a transfer in the corporate world it’s a helpful primer for thinking.

And one of the things – they argue that too often new starters, especially new leaders or managers rush into a new role thinking they have all the answers, rather than actively listening to those they’re starting to working alongside or manage. The book encourages you to get comfortable with asking lots of listening conversations rather than feeling you need to contribute immediately without knowing the whole context.

2 – Plan to do your induction twice – thinking back to my first few weeks at the end of 2016, they were a bit of a whirlwind. Lots of short induction conversations, stacks of documents to read and the desire to be seen to be contributing to the organisation.

By Christmas, I was exhausted, so I found it really helpful to go back after the break with a plan to have a second round of induction meetings – creating a chance to ask some more questions, build better relationships with key colleagues and actually start to feel like I understood what was going on!

3 – What’s your ‘one or two big things’ – Sometimes the ‘one big thing’ is clearly set out for you by your new manager, but I found it really helpful to think about a small number of projects I wanted to get stuck into at the end of a phase of listening. It meant I could be focused, feel like I was contributing back to the organisation and having an impact. For example, one of the areas I wanted to focus on was increasing the variety of the campaign approaches we were using, as we’d become a little wedded to ‘email your MP actions’, the process of working with colleagues, and happily a year later we’ve done a real variety of actions which I’m really proud of the team making happen.

4 – Remember ‘culture eats strategy for breakfast’ – it’s one of those hideous management truisms that you see written on blogs like this from time to time, but it is in my experience true. So spending time understanding the culture of an organisation is so important. Obviously, you want to do a fair amount of that before you start in your new role, but so much of culture isn’t written down, so actively trying to understand it can really help to make sense of why decisions are being made. In saying this I’m not suggesting you have to completely accept the culture you encounter, sometimes things need to change, but understanding why things are approached in a particular way is an important first step.

5 – Keep outward focused – one of the first things that I found slipping out of my diary was external meetings or catch-ups with colleagues in similar roles across the sector. I soon came to appreciate that this wasn’t good move. It’s especially true in a big organisation where processes can consume lots of your time. If you’re someone who gets energy and ideas for seeing what others are doing make sure you protect that time and use it to bring new ideas to your organisation.

6 – Decide on your new habits and try to keep to them – Ahead of joining Bond back in 2014 I read Charles Duhigg book, ‘The Power of Habit’ and how new starts can be great opportunities to change your habits. For me that meant one area I thought a lot about was the management habits I wanted to employ, I took time to make sure I was clear on what I wanted them to be, and how I could go about creating habits that meant I stuck to them. I’ll be honest a few have fallen by the wayside, but many of them are now firmly embedded as habits. If you’d like to read more about leadership in campaigns, then this might be of interest.

7 – Write a ‘not to do yet’ list – I found in the first few month that it was easy to say ‘yes’ to everything, in part because I wanted to be seen to be doing a good job, but also because I had time and capacity because other projects were still taking off. It’s an easy temptation to get into, but a year later I’ve found having put together a ‘not to do yet’ list has been really helpful – for me it’s a list of projects or areas of work that I’m keen to get more involved in, but have held back from to ensure when I do I can do so confident in the capacity.

8 – Ask for feedback – One of the many things I really value about Save the Children is a culture of feedback. I’ve found it really useful to be able to get formal and informal feedback on what I’m doing, especially as I’m starting. I know it’s something that I still need to work on. And I know that some of my colleagues read this blog (hi!) so I hope they’ll be generous in providing feedback in the comments below or in-person if I’ve been inaccurate in what I’ve shared!

How to sustain the energy in your campaign

I’m off to chat to the good folk in the campaigns team at Battersea Dogs and Cats Home later today about how to keep the energy going in your campaign. It’s been a really fun question to be thinking about – not least because I can use a cute cat picture to illustrate this blog.

But as I’ve been preparing I’ve been struck that we often spend so much time and effort on planning the launch phase of our campaigns but don’t think about how to sustain the energy and momentum that we need to secure change.

As, George Lakey, said in his London lecture earlier this week, “a campaign, in contrast to a protest, is going at it over and over again, and escalating at the point of vulnerability of your target until you succeed”.

So here are 9 thoughts about sustaining the energy in your campaign;

- Think about the moments that people care about not moments you care about – too often we focus our campaigning around pushes that fit our policy calendars. There can be a rationale to that, but why not look at alternative moments that might help to get your campaign noticed in an a different light.

- Mind the moment gap – thinking about moments means that we can get caught forgetting what’s going to happen in the gaps. It’s hard to sustain the same level of output for a long period of time, but planning ahead and thinking about how well placed media work, a opinion poll or another approach.

- Ask what’s working/what’s needed – if you have allies inside your target, why not ask them what’s working or not working. What tactic could help to make the biggest different at that moment. They might make suggestions that you’ve not thought about or how to open up a new flank in your campaign.

- Share, and re-share, great content – shareable content is king, but too often we produce it without thinking about audience insight, or rush to move onto the next great idea without pushing it out enough. In a time when we’re bombarding by so much content, repackaging and reusing content is too often overlooked. The same goes for message discipline, I’m struck by how much time Shelter put into repackaging the same message in their housing campaigns.

- Never let a good crisis go to waste – it can be easy to see crisis as moments that you can’t plan for, but I’m not sure that’s true. Most crisis can be anticipated even if the exact timing can’t be pinned down. They’re great opportunities to reach new audiences or create a renewed push behind your policy ask. I thought Which? did this brilliantly around the RyanAir flight cancellations recently – they presumably know that a crisis was going to occur and had the content ready for it. What’s the equivalent for your campaign issue?

- Explore allies and alliances – bring in new people to your issue by thinking about how you can take it too new audiences. Too many campaigns try to focus on energising the same group of people to get involved over and over again, but those that are able to reach out to new groups can immediately bring in new energy.

- Claim it – Campaigns with big ambitions can sometimes lose energy and momentum, but like your teacher would have advised you when planning your revision timetable, it’s easier to eat a chocolate elephant a little at a time.

Breaking down your campaign and building in winnable milestones can really help. We’re running a campaign on the conflict in Yemen at work at the moment. It’s a big problem to solve but by focusing our campaigning on milestones, like getting the UN to list the Saudi led coalition in a key report, has helped to provide milestone win to keep supporters feeling like the actions they are taking are making a difference. - Give it away – provide campaigners with the tools and content to make their own and get out into their communities – it’s a key approach that many distributed campaigns take, allowing the energy and ideas of those closest to a community to engage in a campaign.

- Abeyance – while many campaigns are right to keep going, sometime a period of abeyance can be the best approach, a period when a campaign isn’t in public view. We perhaps sometimes forget that it took over 100 years for the campaign to end the Slave Trade to be successful.

What other ideas and lessons do you have about how campaigns can sustain the energy needed to win?

Inside a failing campaign – lessons from the Conservative 2017 election effort

Regular readers will know that I believe you can learn as much from an unsuccessful campaign and you can from a successful one.

Conservative Home editor, Mark Wallace, publishes a three part insider look at why the Conservative campaign failed at the General Election (part 1, part 2 and part 3). It’s a really great set of articles which gets under the bonnet of what did and didn’t work at an operational level – rather than too many post-elections which focus on the personality clashes between competing politicians. As an aside, I’d also recommend Mark’s writing on the referendum campaigns.

Although the articles are written with the intention of trying to change practice in the Conservative Party going forward, there are a number of lessons that I think can be applied whatever issue your working on. I’d strongly recommend that you read at least the first two articles, but here are the takeaway lessons that I’ve taken from the articles;

1 – You can’t fatten a pig on market day – the famous saying of Conservative election guru, Lynton Crosby, as a reminder that successful campaigns take months, sometimes years of meticulous planning. That it takes time to have the right staffing infrastructure in place, message testing done and materials ready to go. It really is a process you can’t rush.

2 – Get the right people on the bus – successful campaigns need the right people, with the right experience, making decisions at the heart of them. Wallace’s articles include numerous about the lack of clarity in decision making, too many people involved at the tops and the fact that many experienced staff had been let go after the 2015 election. You need to have the right skills and experience to win.

3 – Practice open loop listening – Conservative activists on the ground were repeatedly finding that the data selections that they were being given we’re missing often known Conservative voters, but despite feeding that upwards the data selection stayed the same. Those at the center of the campaigns were so sure that their models were correct the ignored what those on the ground were telling them, a classic example of closed loop learning.

4 – Data deteriorates fast – at the end of the 2015 General Election, the Conservatives had over 1.4 millions usable email addresses, but fast forward just 24 months, and the articles suggest that up to much of this data was out of date (as a reference between the 2010 election, when they had collected 500,000, and 2013 when they started planning for 2015, the list had shrunk to 300,000). A reminder that any campaigning organisation needs to be proactive at continuing to collect data.

5 – Distributed v’s Centralised – the campaign was heavily centralised, with a focus on a few core messages – remember ‘Thresea May’s Conservative Party’ and ‘Strong and Stable Leadership’. This meant there was little space in literature for candidates, who often have a much better sense of what messages would work in a community. That lead to big errors, for example literature featuring quotes from The Sun being sent to seats in and around Merseyside where their is a significant anti Sun feeling, but the same approach surely meant the Conservatives missed opportunities for picking up effective local campaign led by candidates. As a contrast, Ben Pringle has some reflections on how localised campaigns helped the Labour Party

6 – If it ain’t broke don’t change it – Following the 2015 General Election, the Conservatives had found a number of effective approaches working both in individuals constituencies, and how to make the most of working with activists. But many of those approaches were thrown out for 2017. Sure innovation and changing approaches is important, but not at the cost of the basics that have been proven to work.

7 – Message amplification – Wallace reflects on the role that a range of third party organisations and individuals were active at amplifying the messages coming from the Labour Party – the micro-PAC phenomena I’d highlighted in this post – while the same didn’t happen for the Conservatives. A good reminder that the reach of your own social channels, however large, can only get you so far, and you need to build a wider network of support. See more on this over at Political Advertising.

8 – Don’t forget to say thank you – Imagine you’ve just put your life on hold for 8 weeks to run to be a candidate, you’d expect in the days or weeks after election night that you’d get a personal thank you for those who’ve lead the campaign. That didn’t happen for most Conservative candidates, they got a generic email, sent to thousands of other helpers, and that was about it. Not good for motivation!

If you’ve read the articles, what other lessons are you taking from them?