Assuming a catastrophic polling failure doesn’t happen, tomorrow Sir Keir Starmer is going to be the next Prime Minister, and Labour is going to form the next Government with a significant majority – so like lots of changemakers I’ve been thinking about what that means for engaging with the next Government, especially given it’s the first time in 14 years.

Here are a few key reflections I’ve got about how to approach that:

Access does not equal influence – it can be easy to think that being invited to be part of a conversation, roundtable or consultation means that you’ve got influence, but as I remember from a very old NCVO campaigning guide I read back when I started my campaigning work – access does not equal influence.

Indeed consultations and roundtable can often be processes designed to keep stakeholder ‘busy’. Of course, being in the room and the conversation is a great starting point, but it’s dangerous to think that just because you’re ‘in the room’.

As we approach a new government, changemakers are going to have to show what they bring to the conversation – a constituency of support (that can be mobilised), expertise, policy ideas, or something else – rather than just assume ‘being a charity’ means you’ll be invited into the room.

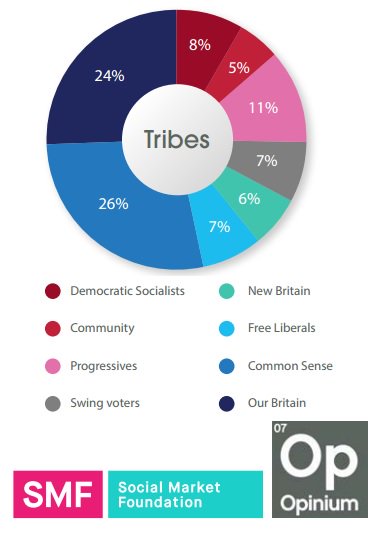

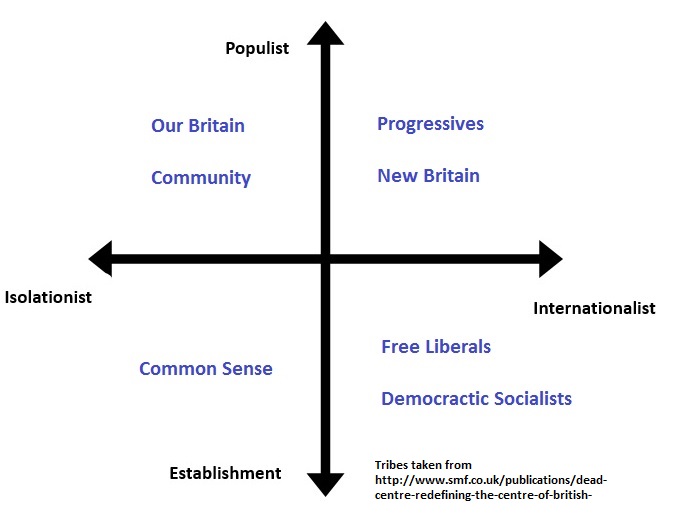

With a significant majority, it’s time to remember that like any political party, there are groups and factions within the Labour Party – as this article suggests, the challenges for Labour could come from within the party as much as from the opposition. So spend some time reading about Labour’s founding and right from the start it’s been a party that has drawn a range of different intellectual traditions together.

That continues up until today – with different factions and tribes within the Labour Party having different levels of influence and roles to play within the Parliamentary Labour Party.

It’s really worth the investment of time understanding them – and thus how decisions on how you engage with MPs who align with different parts of the Parliamentary Labour Party will inform how your approach is viewed.

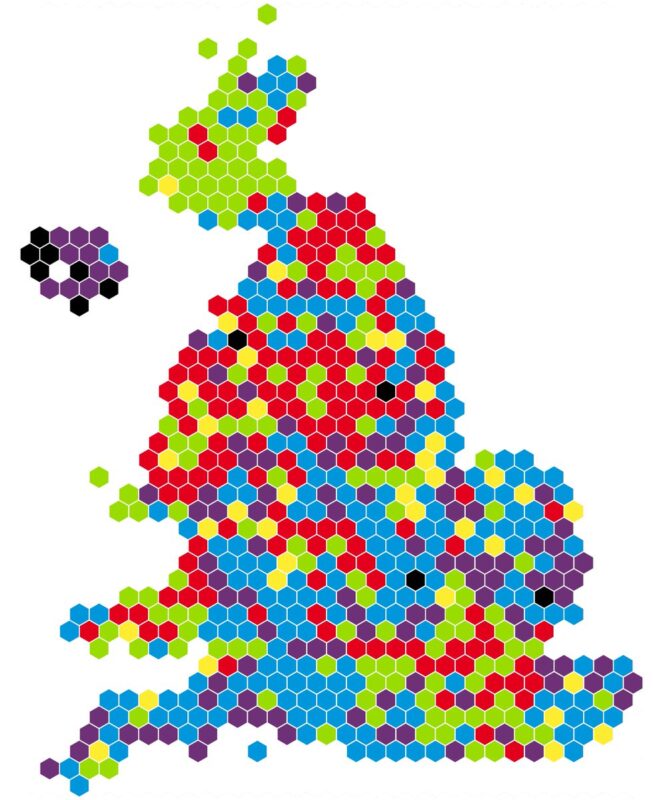

Pay attention to the post-election narratives that emerge – for the last few years countless articles have been written about the ‘Red Wall’ and how it was the key battleground for future election. What voters in the Red Wall think has shaped the political decisions of the last 5 years – and the same will happen after this election.

Narratives will emerge about what was behind the result and what it means for the decisions that a new Government can make. Some organisations are able to try to shape and influence those narratives – others aren’t, but being aware of them, and what that will mean for the political landscape of the next 5 years.

Give new MPs some space – looking back at this post from 2011 I’m reminded of this one – where Dominic Raab (whatever happened to him) complained about being overwhelmed with messages from constituents.

He was at the extreme end of what was happening, but it’s a useful reminder than for many MPs they’re going to spend the first few weeks of the new Parliament getting offices set up, working out how to navigate around Parliament literally and figuratively, and pick up casework from their predecessors – while at the same time being exhausted from 6 weeks of campaigning.

Giving them a little space before you lunch into your pitch might actually yield better results.

Keep calm and make friends – if Labour gets a significant majority, then there are likely to be a significant number of MPs without any formal roles in Parliament (for example on Select Committees) or within Government.

Many will be wanting to ‘tow the line’ until the first reshuffle happens – in the hope that they’ll be viewed favorably for promotion. That will all change after that reshuffle has happened as the ‘winners’ and ‘losers’, but even before then it’s also a great opportunity to work with new MPs who are interested in the issues you’re working on.

Don’t overlook the opposition – it’d be easy to go ‘all in on Labour’ with any influencing strategy at the moment given the likelihood of a sizeable majority, but as retiring Green MP, Caroline Lucas, reflected in this lecture last month, there is still lots a loan MP can do using the Parliamentary processes that exist.

And that will be true for the opposition parties as well – if the Lib Dems pick up seats what are the opportunities to work with them on getting issues discussed and debated, and even if the Conservatives spend the next 12 months having a argument about the direction they want to go in, are their individual MPs you can look to work with.