The Engagement is Sasha Isssenberg’s (author of the Victory Lab which is another must-read) latest book, and it’s the authoritative book on the campaign for same-sex marriage in the USA,

An absorbing if long read that wonderfully intertwines the stories of those involved in the campaign, with the lessons and reflections on what did and didn’t work for the campaign.

It’s a great contribution to a lot of other useful writing on the campaign (I’d also recommend this) and I’d really recommend a watch of some of the online discussions that Sasha did as part of the promotion of the book, or a read of this.

As I read the book I noted down a few of the lessons that I think are applicable to all movements – most from the winning side, and one from those who opposed it.

- Set out a clear plan for victory – advocates came together on multiple times to set out their shared strategy and playbook. The book makes it clear they didn’t always agree on the approach, but nevertheless spent time developing collective plans together and understood the role that different actors were going to play.

Together they set out a ’10-10-10-20′ strategy looking at how the approaches in different States and the tactics and resources needed. I was struck by the sense of farsighted the movement had been. - If you’re not getting anywhere with political processes, build pressure from outside politics – advocates for a time focused on corporates to try to recognise the rights of their gay staff to access healthcare for their partners and other rights to grow pressure from other routes on political decision-makers.

- Build a funding infrastructure committed to the 4 ‘multis’ – multi-year, multi-state, multi-partner and multi-methodology. I hope many movement funder will read the book – it’s a reminder that if we just aim to fund a slice of what we think is needed we will probably fail.

- Learn from past issues and campaigns – advocates spent time learning from the success or failures of others movements in the US such as abortion rights activists. We need to be students of what others have done, so we can learn and apply what might work for us.

- Recognise the importance of divergent tactics – “there are many methodologies for social change and we really need them all pulled together in partnership and working to make the whole greater than the sum of the parts”. That can be uncomfortable when working in movements, but we shouldn’t forget it’s importance for our collective impact.

- Obsess about what works – advocates established the Movement Advancement Project to assess the effectiveness of what approaches were working and not – and help funders to surge behind those that were.

- Focus on messaging as well as operations – ensure you’re clear on who your audience is, and continuously develop your messaging. “no matter how many people you train and deploy to go canvassing, if you can’t figure out your message, you are dead in the water”

- Try new approaches – that helped the movement develop it’s ‘deep canvassing’ approach which focused on interactions that where seeking to change the views of voters as opposed to simply focus on identifying new and existing voters.

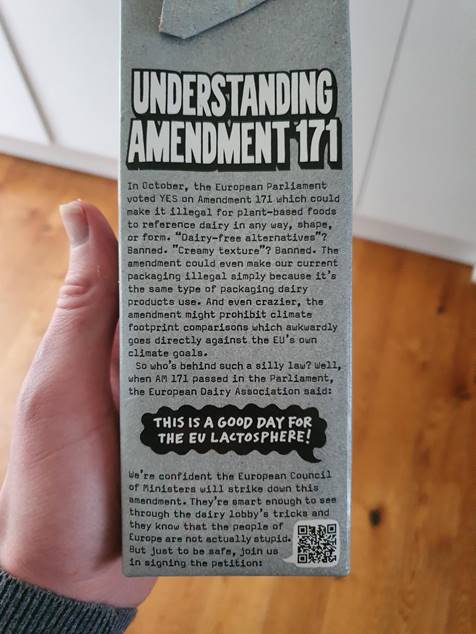

- And one lesson from the opponents – trendspotting – opponents of equal marriage had a well resourced campaign, but also benefitted from a network of individuals within their network who effectively acted as trend-spotters. Looking for up-and-coming issues ready to make the jump from niche policy interest to mass concern.

10. Ask tough questions – finally, reading the book reminded me of this excellent article on questions proponents were forced to ask themselves and honestly answer, which seem vital to any successful