Between the election, a busy period at work, and family life, blogging has slowed down towards the end of 2019 – that’s something I’ll be aiming to fix in 2020.

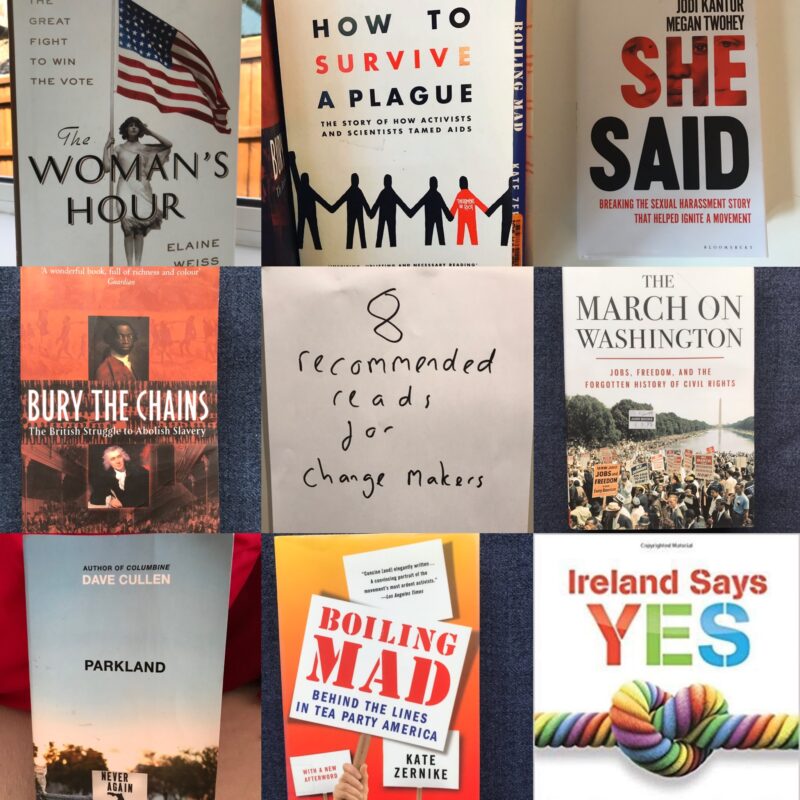

To be honest, I didn’t find 2019 to be a classic for books for changemakers, and many of the books I’ve most enjoyed have been those that have told the stories of movements in the past that have successfully won change – while acknowledging there are lots of other movements, especially from outside the US and Europe that’d I’d be keen to learn from and not reflected in the list.

I think curiosity about how change happens is a vital attribute for any campaigner and have found that looking back at the past can be one of the best ways to learn how to win in the future, and in our current turbulent political times, I’ve found that reading up on movements from across the ages has been important for remembering the principles that should be at the heart of every campaign.

So here are some of my recommendations;

Bury the Chains: The British Struggle to Abolish Slavery by Adam Hochschild (Amazon/Hive)- the classic text of the successful campaign of the abolitionists, led by William Wilberforce to end the transatlantic Slave Trade in the 1800s, but as you read it you also discover the campaign pioneered many of the tactics that we still use today, like petitions, direct mails, and boycotts. Max Lawson has written a good review of it here, but the book has too much focus on the role a small number of men played in the campaign. I’m definitely looking for texts in 2020 that correct that.

The Woman’s Hour by Elaine Weiss (Amazon)- this book explores the successful campaign to introduce women’s suffrage in the United States – and in particular, focuses on the efforts to ratify the 19th Amendment in Tennessee – the 36th state needed to become the law of the land. The book is rich in exploring the tactics used, and in particular, the important role that different actors played with the suffragette movement, and the recognition that successful movements often require leaders and organisations that take – as Weiss writes ‘rifts within protest movements appear to be an essential component of the ecosystem of change’.

Ireland Says Yes by Gráinne Healy (Amazon/Hive) – a brilliant playbook on how to win a referendum written by the leaders of the equal marriage campaign in Ireland – it’s a fascinating insider account of how the campaign identified that to win it needed to focus on the ‘moveable million’ those who were neither a hard yes or no for marriage equality, were more likely to be persuaded by people like themselves, and then pursued a strategy to deliver that, including key decisions about how the campaign messaging was going to be framed and the messengers to be used. ActBuildChange has a great summary here, but for any campaigner, looking to understand the importance of identifying a winning narrative I can’t recommend it enough.

The March on Washington: Jobs, Freedom, and the Forgotten History of Civil Rights by William P Jones (Amazon/Hive)- there is such an extensive literature on the Civil Rights Movement – I’ve had Taylor Branch’s King Era trilogy on my shelf for a few years, but I’ve chosen as it’s a really good look at one of the most pivotal days in that movement, it is, of course, the day is remembered for the I Have a Dream speech, but I found the book to also look at the critical role that many played in arranging the logistics and mobilising for the day and the level of practical detail that went into organising the day – for example having lunch packs available to all marchers and a sound system that could be heard – a reminder that movements require different leadership roles.

Boiling Mad: Inside Tea Party America by Kate Zernike (Amazon/Hive)- The rise of Tea Party may have been over a decade ago, but I’ve found the literature to be some of the most interesting in how movements grow – none more so that Kate Zernike book which looks inside the grassroots groups that mobilised following the election of Barack Obama – and while there is nothing that I’d agree with the Tea Party on the book gives an excellent account of how the movement grew so rapidly, and how much they studied there opponents to learn from them. A reminder to campaigners to understand the approach those you’re campaigning against is taking.

I’d also really recommend Theda Skocpol The Tea Party and the Remaking of Republican Conservatism – it’s a more academic look at the rise of the Tea Party, but again gives clues to how it grew so quickly, and foretells how some of the infrastructures that were built by the Tea Party helped to propel Donald Trump to the Presidency in 2016.

How to Survive a Plague: The Inside Story of How Citizens and Science Tamed AIDS by David France (Amazon/Hive)- this isn’t a quick read, at 400+ pages it’s the longest books on the list – but I found David France’s account to be utterly absorbing and very moving account of how a small group of activists took on the pharmaceutical industry, mastered the complexities of HIV and the clinical trials process to gain the respect of medical researchers.

The book brings an eyewitness account of the activism that got the US Federal Drug Agency to finally change its position, the role of Act Up (Aids Coalition to Unleash Powe ) and it’s direct and creative activism which forced action – warning it’s a book that will make you angry. There is also a critically acclaimed film of the same name which is recommended.

Parkland: Birth of a Movement by Dave Cullen (Amazon/Hive) – a very contemporary recommendation to add to the list, but one of the best books I’ve read this year, Cullen spend almost a year embedded with the leaders of March for our Lives. If the last few years have been dominated by youth activism, then this is one of the best accounts that I’ve read of how youth-led movements have driven so much action. I did a quick Twitter thread on some of the key lessons that I took from the book here.

She Said by Jodi Kantor and Megan Twohey (Amazon/Hive) – this is the insider account of how two New York Times journalists broke the story of Hollywood producer Harvey Weinstein’s decades of sexual aggression against both A-list actors and junior employees and the subsequent rise of the MeToo movement. It’s fascinating and well researched read, and a reminder for campaigners of the important and critical role that journalists can play in breaking stories that allow change to happen.

A note on the links – where possible the links to take you to the hive.co.uk – an independent online bookseller, but I’ve also linked to Amazon, I earn a small commission from Amazon for each sale using the link which I use to cover the costs of hosting this blog.