My friend and former Tearfund colleague, Sam Barker passed away last month, after a short but brave battle with bowel cancer. You can read more about Sam in this obituary here.

For the last few weeks, and at his funeral last Friday, I’ve been carrying around with many many thoughts about Sam; about what he taught me, about how he made me, and so many others he worked with, better advocates for change.

So I wanted to write some of that down as a small tribute to one of the very best people I’ve had the chance to work alongside to change the world, in the hope, it might help others.

Dear Sam,

I still remember properly meeting you for the first time, we sat in Portcullis House as we chatted about politics, what it was really like to work for an MP, and because it was a Friday it was definitely a ‘dress down’ day in Parliament!

You’d been kind enough to reply to a post I’d written suggesting we should all start to encourage our supporters to be ringing their MPs. There I was, the impatient campaigner, as you shared for me what it was really like working for an MP and how that perhaps encouraging everyone to start phoning wasn’t a very good idea!

Since your passing I’ve spent lots of time reflecting on everything that you taught me, and the things that I wish I’d said to you, so I hope you don’t mind that I’ve captured, and shared a few of them.

In many ways, the first encounter was so in keeping with my memories of you, always be generous with your time, advice and expertise. You didn’t need to take that time to meet with me; but you didn’t want to keep the insight and experience you had, you wanted to share it with others in the hope it would help me be a better advocate.

I remember at the first Bootcamp, you added yourself to the seed list and took the time to send really insightful feedback to that cohort, who used that to help them become better campaigners. In the last few weeks, I’ve heard others share similar stories of their first meetings with you, and they all have that theme of generosity and kindness at the center of them. You taught should never to become too busy or self-absorbed not to take the time to offer thoughts and advice to others.

And I think it was that spirit, that meant you knew that change wasn’t going to happen without building a bigger tent, opening it up to welcome and include others. History is good at celebrating the figureheads of movements but isn’t always as quick as it should be at recognising the tent builders. Those who do the hard work of connecting people together, remembering that the most effective movements are the surprising coalitions. It’s so clear in the work you did across your career was about building a bigger tent in pursuit of a fair and just world.

The words of Jo Cox have come back to me on so many occasions in the last few weeks – that we have more in common. I don’t suspect we’ve ever voted for the same party at an election, you were a proud Conservative. I am, at times, an overly tribal member of the Labour Party (although perhaps less so at the moment), but those words that Jo shared “we are far more united and have far more in common with each other than things that divide us” keep coming back to me.

You taught me more than anyone else I’ve known that whatever the political tribe you choose to be part of, that it’s the job of changemakers to look to make common cause. You taught me over and over again to look beyond the political tribe; that there are individuals in all parties who are committed to addressing the big challenges – we might have different routes to get to the outcome, but we will achieve those quicker if we work together.

To wrestle with the question ‘are we really making a difference?’ – it’s so easy to get caught up in the doing, but I remember many of our conversations had that question at the heart of them, over coffee or beer, asking, pushing, probing if the work you were doing was making a difference – and if not what would be more strategic. What I really admired about you, was the way you didn’t shy away if that question came with a difficult answer and I hope you realise just how much of a difference you did make.

That this work needs to be fun – there is a picture a colleague from Tearfund shared a few weeks ago, of you at the George Osborne event as part of the IF campaign – you appear to be in your element with your George mask in hand. It’s a reminder, that in the seriousness of the work of bringing an end of poverty, ushering in a greener and fairer economy and caring for creation: we need to have fun, to laugh, and to get stuck in with whatever is happening – even if it means an early start dressing up as George Osborne! I loved that about working with you, for all the seriousness of the work, you brought fun and laughter into the center of it.

But perhaps most importantly, you taught and challenged me to bring your whole self to the work of making change. As a Christian, it can be easy to hide that away in the campaigning arena – to avoid the difficult questions that can come with it. But you challenged me by your example, it was so clearly your Christian faith that brought you to the work that you did and that faith that shone through until the end. You showed me that we can’t leave our faith at the door of the office, but need to unashamedly acknowledge that it’s the guiding force and sustainer behind the work of bringing change to a broken world.

I could write more, and I’m sorry for not saying this to you in person, but thank you for everything you taught me. Like so many others I’m really going to miss you,

Rest in Peace and Rise in Glory,

Tom

Author: mrtombaker

When is a petition, a BIG petition?

A colleague asked recently – what I’d consider a ‘big’ petition number.

Putting aside the discussion about the role of petitions in campaigning and their effectiveness, plus the reality that a big petition is so dependent on the context that it’s being used as a tactic for – if you get 1,000 people in a village of 2,000 to call on the local parish council to take action on something then I’d argue that’s a ‘big’ petition.

But given the discussion was about influencing Westminster and Whitehall, I decided to dive into the data that’s available on the Parliament Petition site. It’s a site that I’ve had misgivings about in the past, but one thing in its favor is that it does make the information really easily accessible by allowing you to download it in a format that means you can manipulate the date.

The Parliament site already sets some suggestions of what it considers to be a significant petition – if you get 10,000 people to sign you’ll get a government response, and 100,000 could mean that the petition will be considered for a debate.

So working on an assumption that anything that gets over 10,000 must at least get on the radar of the relevant Secretary of State or Minister – because presumably, the response gets put in the ministerial red box, and if it’s 100,000 they need to attend the debate, so I decided to look at every petition that had got over 10,000 signatures since the start of the current Parliament – a total of 165 petitions when Parliament went into recess for the summer (the number is now at 174).

So what did I find out?

I’ve made the whole dataset available to download here. I went through each response to code them against the government department that was asked to respond as a way of identifying who they targetted.

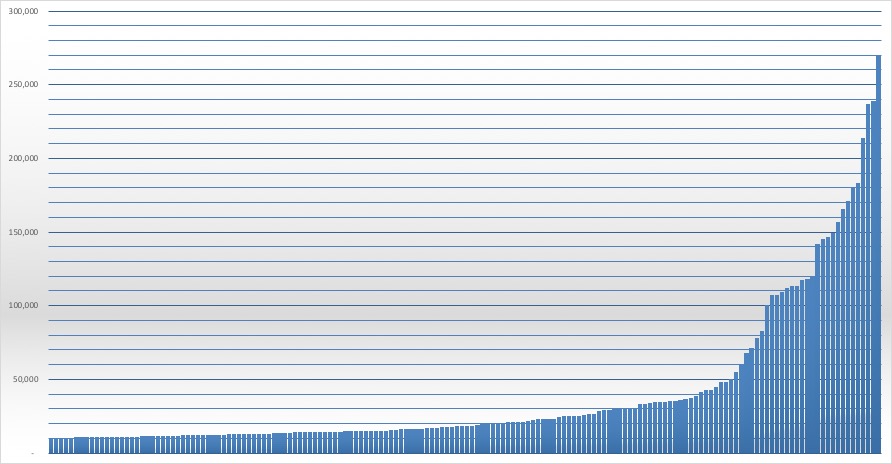

1 – There is a very long tail – even when you’re looking at just those petitions that get over 10,000 signatures, it’s very much the case that you find a few petitions with very large numbers of signatories – there are 4 current petitions with over 200,000 signatures.

It’s useful to look at the largest petitions that each department has received, as it gives an indication of what might be considered ‘big’, and for many departments – they’ll be the recipient of one very significant petition and lots which are closer to the initial 10,000 thresholds;

2 – Some departments receive lots more petitions than others – Officials at the Department of Health, Home Office and Department for the Environment have been kept busiest having to respond to the most petitions over the last 18 months, each dealing with over 25+ petitions, compared to just 1 for DFID, Northern Ireland Office, Minister for Equalities and Leader of the House (who had to respond to a petition about subsidised meals in the House of Commons). The average for a department is 6.

3 – Getting over 50,000 is a significant milestone – there are only 7 petitions in my dataset that are between 50,000 and 100,000, 22 which have gone beyond 100,000, and just 4 over 200,000 – so 20% get over 50,000. Of course, the challenge here is that officials and ministers are only obliged to respond when the petition hits 10,000 or 100,000, but if you’re looking for a sense of what’s a big petition then anything over 50,000 feels like it is.

4 – Looking for an average number? Then this really does differ by department, with the average number of signatures that get on to the radar of the relevant ministerial teams going from around 20,000 for departments like Transport or the MoD but up to closer to 75,000 for the Treasury and over 100,000 for BIS. The Department of Justice has the highest average of 115,000 but that’s based on just two petitions – one of which has got over 210,000 signatures.

If you’re looking for an average number across government then the mean average is 39,932 and the median average is just 18,189 – which shows the impact of the handful of very large petitions on the overall total.

5 – Other petition sites, of course, exist – this is just data from the Parliament site, and of course many petitions are set up with 38 Degrees or Change.org, as well as on agency-owned platforms, but a quick look at the petitions set up towards the FCO, a department I have a particular interest in for work, suggests that the numbers for actions on those platforms aren’t dissimilar to those on the Parliament site, but there are a few organisation petitions that are much more significant. (As an aside if anyone from change.org or 38 Degrees wants to provide me with a similar data set I’m happy to add this in!)

So what makes a big petition? Well with lot’s caveats, but from the data, I‘d suggest that anything over 50,000 could be considered a big petition to the government. It’s a clear milestone that most petitions don’t get over and it’s a number that can’t easily be dismissed as an ‘average’ number, but I’d be interested in what other readers think.

Summer Viewing – 5 great campaigning films on Netflix

It’s the summer holidays, so I’m going to take some time off from blogging – normal service will return in early September – but if you’re looking for some campaign inspiration here are 5 great campaigning films on Netflix.

1 – Joshua: Teenager vs Superpower – a brilliant film following Joshua Wong, one of the organisers behind the Umbrella Revolution, that saw young people in Hong Kong mobilise when the Chinese Communist Party reneged on its promise of autonomy to the territory. It’s a brilliant portrait of courage, and an insight into a movement that hasn’t got as much coverage as others in the UK.

2 – The Square – another insider look at the Tahir Square revolution in Egypt. It rightly got lots of critical acclaim when it first came out, and while it’s a few years old it’s still a fascinating look inside a movement that gripped the world’s imagination back in 2011.

3 – The Final Year – a fascinating look inside the foreign policy work of the final year of the Obama White House. While it’s easy to warch this film and reminisce about a different political time, it’s also a really interesting look at how decisions get made inside a government, and the interactions with other governments, the media and political opposition. If you’re looking for something at the opposite end, then Mitt is a look inside the failed 2012 campaign of Mitt Romney, but again gives a great inside account of how political campaigns run.

4 – 13th – one of a number of excellent documentaries available on Netflix, 13th explores the intersection of race, justice, and mass incarceration in the United States, while Nobody Speaks looks at the role of the free press, along with many others in the documentary category.

5 – Reporting Trump’s First Year – The Fourth Estate – not on Netflix, but this excellent 4 part Storyville documentary which goes inside the New York Times newsroom is worth catching while it’s still available on the BBC iPlayer. It’s a great look at how political journalism operates and some of the challenges of breaking news in an era of Twitter. If it’s not available, I’d also recommend Page One – Inside the New York Times.

What happens if you don't open any campaign emails for a year?

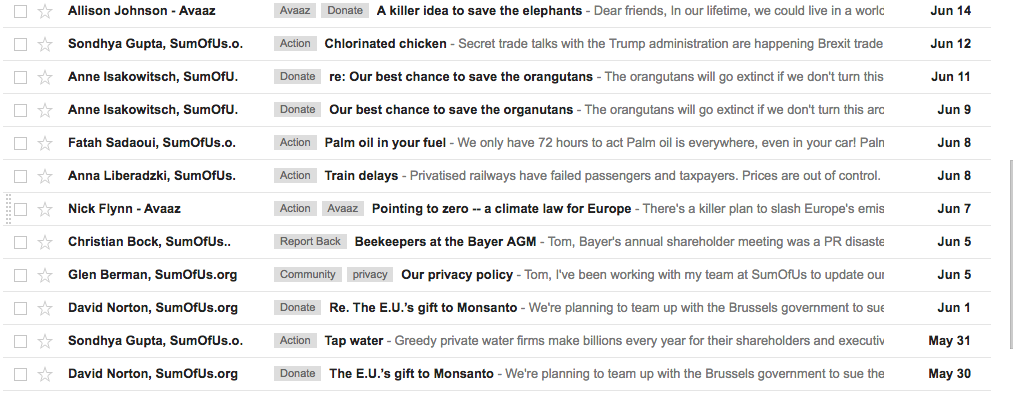

Last year I started an experiment, to sign up to a bunch of campaigning organisation, and then find out what happened if I said ‘yes’ to every request they sent to me.

So for a month, I did that for every email I got from 38 Degrees, Avaaz, Sum of Us and We Move. Over a month I signed petitions, emailed targets, donated, participated in surveys and RSVPd for events.

The plan was to continue to do this into 2018, but then an election was called, and my inbox took a backseat. In fact, I didn’t open a single email from any of the above organisations for a year, but then I got interested again.

A year later, would I still being treated like a very enthusiastic campaigner or a lapsed one, would anyone just stop sending requests to me, what might happen as a result of GDPR and would I see any effort to re-engage me?

So, in late May, I open that inbox again, to be welcomed by 431 emails – sent between 14/5/17 and 14/5/18 – so well over 1 message per day, which broke down as follows;

| # of email | Frequency | |

| Sum of Us | 179 | every 2 days |

| We Move | 58 | about once a week |

| Avaaz | 100 | every 4 days |

| 38 Degrees | 103 | every 3 days |

Digging into the results it’s really interesting to see how the different platforms – which are often lumped together as ‘campaigning first’ organisations take some very different approaches to campaigning, for example, the frequency of fundraising emails and the fact that most aren’t using community surveys to power what they focus on as a platform, to some of the more subtle testing of different templates

I was expecting to see more stewardship as I moved from an active to dormant supporter who hadn’t taken action for over a year, but only 38 Degrees got in touch to ask if I was still interested in hearing from them – all the other platforms just continued to serve up a very similar digest of emails.

I also used the arrival of GDPR at the end of May to send a request to each organisation to provide me with the information they held on, which you’re meant to provide within 28 working days, as you’ll see below that’s something some, but not all organisations have been able to provide.

Sum of Us

Sent me 170 emails which broke down as follows;

| Action | Sign a petition, etc | 69 |

| Community | Join a community event or protest | 8 |

| Donate | Give money | 69 |

| Share | Amplify via social media | 10 |

| Survey | Share my views | – |

| Report back | Feedback on activities | 14 |

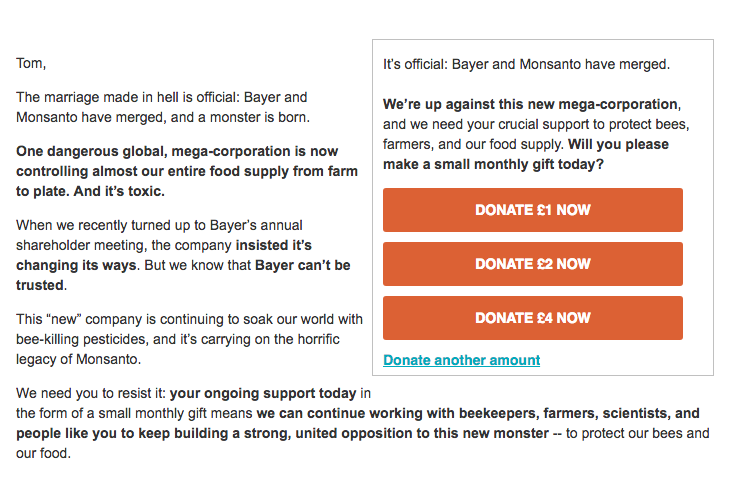

That works out as 1 email every 2 1/2 days, although sometimes Sum of Us would actually send me up to two emails every day, and as many fundraising emails (each asking me to chip in a few pounds) as action ones – something that is clearly working as according to their 2017 annual report they raised $3.8m from donations in 2016.

The only change in the types of emails I got was any of the more community focused requests stopped coming from June 2017 – for example when I was really active I was invited to webinars on data security, and probably as a result of volume of messages sent, but more Sum of Us emails ended up in my promotions Gmail inbox than any other organisation. Sum of Us responded to my information request with a big ZIP file of what information they held on me on their database.

The themes of the emails were a real mix, some campaigns like those on the Bayer and Monsanto merger, and bees coming regularly across the year, with others being far more opportunistic – an email on train privatisation at a period when railway delays were prominent in the news here in the UK – but overall looking back across a year of campaign actions from them it felt like some threads emerging.

I’d written before that I’d been impressed by the approach that Sum of Us took to fundraising and campaign innovation, and that has continued across the year I’ve been away – from actions focusing on a range of targets – for example, I really like the targeting of Liverpool FC when they accepted sponsorship from Tibet Water, and really excellent stewardship emails reporting back at the end of the year, making me feel like a valued member of the Sum of Us community (even if I was rather inactive).

Avaaz

Sent me 100 emails which broke down as follows;

| Action | Sign a petition, etc | 58 |

| Community | Join a community event or protest | 3 |

| Donate | Give money | 27 |

| Share | Amplify via social media | 1 |

| Survey | Share my views | – |

| Report back | Feedback on activities | 11 |

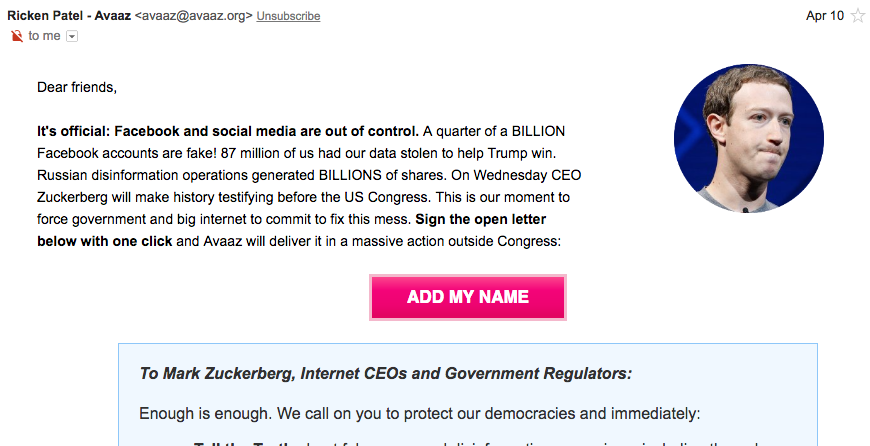

Despite sending almost two emails a week, everyone ended up in the ‘primary’ inbox in my Gmail – which matters as I’m much more likely to read those first when, but I also I found that sometime Avaaz would send me identical emails a few days apart, presumably working based on the knowledge I’d not open then!

As you’d expect with a platform which works on global issues they topics for emails – a few themes that picked up for a while, for example on Gaza, but it’s hard to say that there were campaigns that they were sustaining across the year. Having said that some of the smartest fundraising emails came from them, at a time they were being threatened by Monsanto they asked me to chip in to help support their legal fees – and stand up to.

Like Sum of Us they were also really active at writing regular report back emails – often entitled ‘what happened after you signed that petition’, perhaps an indication that people are sceptical of what indeed does happen when they sign a petition. Oh, and also loved the inclusion of gifs in some of the emails, and variety in action templates.

I’ve not had anything from Avaaz about changes to their privacy policy – and as of the time of writing they’ve not come back to me with my request on GDPR, despite regulations suggesting that they should reply within a month of receiving the request.

WeMove

Sent me 58 emails which broke down as follows;

| Action | Sign a petition, etc | 34 |

| Community | Join a community event or protest | 2 |

| Donate | Give money | 12 |

| Share | Amplify via social media | 2 |

| Survey | Share my views | 5 |

| Report back | Feedback on activities | – |

WeMove also sent me 5 emails about privacy ahead of GDPR

WeMove is less well known in the UK, but it’s a pan-European platform focusing on decisions at an EU level, and perhaps because of that I’ve heard nothing from them since GDPR came into force, and most of the emails from them in May where about opt-in.

I’d have argued these weren’t necessary as I voluntarily opted in at the start of the experiment last year – so I was surprised that they’d not opted me in on their database. WeMove as of the time of writing still hasn’t responded to my information request.

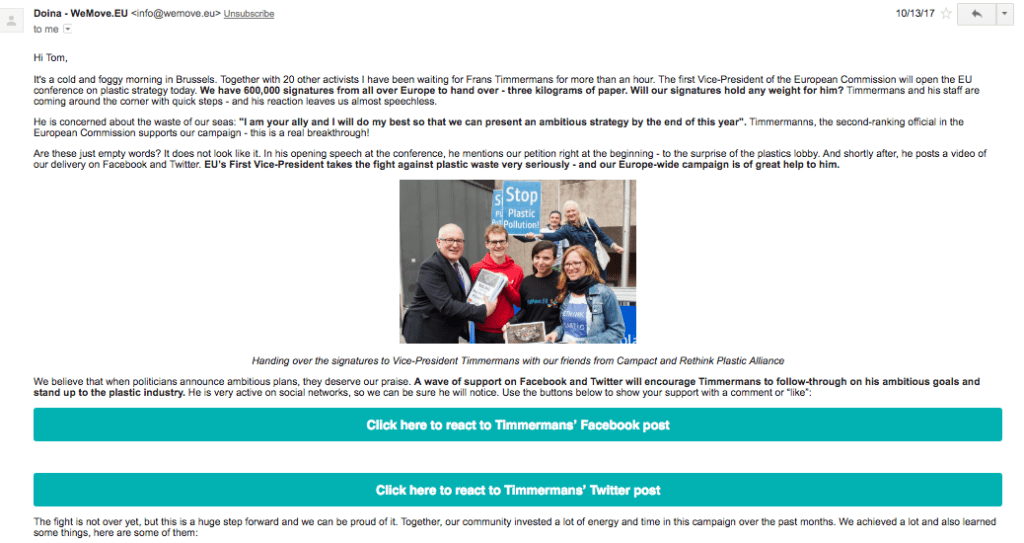

The platform early on relied on using surveys to get a sense of what their members are looking for, but that seemed to drop off in my journey from October. Their emails were generally longer in length than the other platforms, but featured a bunch of interesting innovation in approaches, for example, the email below where they asked me to react on the Facebook page of Frans Timmermans, Vice President of the EU Commission on banning single-use plastics.

The big campaign they’ve been running has been on banning glyphosates – harmful weedkillers that appear in many foods, where they’ve been successful at getting their movement to arrange an EU Citizens Initiative, which requires collecting 1 million petition signatures from at least 7 member states(s).

38 Degrees

Sent me 103 emails which broke down as follows;

| Action | Sign a petition, etc | 60 |

| Community | Join a community event or protest | 11 |

| Donate | Give money | 12 |

| Share | Amplify via social media | – |

| Survey | Share my views | 15 |

| Report back | Feedback on activities | 5 |

That works out at an email every 3 days – but I’ve actually heard almost nothing from 38 Degrees since December 2017, with the vast majority of messages in 2018 ending up in my spam folder. Something that 38 Degrees appears to be aware of as many of their messages ‘Please add 38 Degrees action@38degrees.org.uk to your contact list so that you never miss an email’ so the volume could have been much greater than that.

Unlike the other platforms, 38 Degrees still use lots of quick surveys – asking me to answer just a single question in the body of my email, presumably as a way of getting my attention to take action as opposed to a way of shaping the priorities of the platform.

They also offer longer surveys when they’re looking to get member input into their plans, especially following key external moments like the June 2017 General Election.

They were the only organisation to send me an email asking if I kept wanting to hear from them – referencing the fact that they’d not heard from me in a while, and asking me if I wanted to stay in touch, and were one of the few organisation to send me an updated version of their privacy policy and responded really quickly to my request for my information under GDPR.

Lots of the actions I was invited to take were around the key campaigns for 38 Degrees on protecting the NHS and Brexit, although there was , they’re also the only platform to use lots of personalisation in the subject lines of emails, often mentioning my constituency or MP in it – a subject of some personal frustration if I’m honest as my MP, Rosena Allin-Khan is still a practising doctor so I find the ‘can Rosena Allin-Khan MP save the NHS’ subject lines a little lacking in political smarts!

Oh, and the asked me if I wanted to buy some Christmas Cards from them – which I wasn’t expecting!

Full Spectrum Engagement – blending effective community building practices and new engagement tools

If I’m honest, I’ve been distracted by the World Cup over the last few weeks, but one paper that I really enjoyed reading while I was away on holiday, was Full Spectrum Engagement – Build Community Power to Win Campaigns.

A short paper pulled together by the team behind NetChange, New/Mode and others looking to bring together effective community building practices and new engagement tools,

It draws together threads from some of the most interesting thinking on campaigning that I’ve read over the last few years – reflecting on the work of Hahrie Han, the principles of Networked Change, the insight on New Power, the idea of Big Organising and the Engagement Organising. It’s also built on the back of a stack of research about how those we target are engaging with campaigning.

It’s based on 5 key principles;

- Show how change is possible – show a clear theory of change and how your plan – powered by their actions – leads to the goal.

- Give recognition – make supporters the stars, highlighting those who engaged and sharing their stories of progress.

- Be accessible – meet people where they are, with language and actions that draw them into deeper engagement over time.

- Build meaningful relationships – build relationships and communities, not just lists and data points.

- Share ownership -give community members as much control as you can. listen, and let them shape the campaign with you.

It’s a quick report to read that prompted me to reflect on a few lessons that I can apply in my campaigning work.

1 – Petitions still have a role in our toolkit – it’s become fashionable in some parts to be dismissive of petitions as a tactic to secure change, it’s a view that I know that I sometimes find myself endorsing. But Full Spectrum Engagement challenges those who might hold that perspective to consider the role they can play in helping to engage people. However, we need to be honest that many of those who campaign for us are increasingly wondering if anything will change from the actions that they take – the report cites some interesting research from Google about involvement in civic engagement.

2 – Don’t overlook the ‘mushy middle’ – one of the principles that I found most exciting about the approach is the role that it sees for the ‘mushy middle’. These those campaign steps that fall somewhere between online engagement but aren’t the high bar. How do we use a letter to editors or phone call to decision-makers to help make the step up the pyramid of engagement? They have a strong tradition in campaigning in North America but it feels like in the UK we’re more reluctant to embrace them – but they can be powerful tools in helping to deepen the engagement of campaigners.

3 – Enter anywhere – We spend lots of time thinking about engagement as a ladder or pyramid that you can go up (and down) but that approach limits our assumptions about where supporters will start – and while most will move up – the experience of the Bernie Sanders campaign shows that some people want to jump in higher up, and take on more responsibility, while at other times you’ll need to present compelling ask to get everyone to go deep. Think more about a matrix of engagement.

4 – Have a really clear theory of change – the report cites the examples of campaigns, like Stop Adani, that have really worked to produce sharp and easy to communicate theories of change – suggesting that they help those who support your campaign understand how we’ll collectively achieve change. I’ve often thought about a theory of change as something that’s internally focused, but have found this approach from Purpose really useful to shape my thinking about the role of creating a shared public understanding of what you’re looking to achieve.

Can you campaign complete the following sentence to explain your campaign – ‘If we mobilize (participant) to (actions), we can influence (target) to achieve (goal) in order to (impact)’

5 – Make supporters the stars – reiterating a theme that comes up across many of the works that inform the paper, it’s no longer an option not to involve supporters at the heart of your campaigning, that this needs to increasingly be about giving away control to them, finding ways to get them to involve, shape, inform, and lead. Campaigns that aren’t able to do this are likely not to succeed – and it requires us to build meaningful relationships.

6 – Seek out new metrics? – It feels like lots of reports circle back on this as a theme, recognising that so many of the metrics that we feel most comfortable to use focus on our reach rather than our impact. Building on research by the Open Gov Foundation, I know that i’m going away from reading the report thinking more about how I can develop metrics that speak to the strength of the relationships they have with decision makers – looking to think less about how much reach we can have on a really good day, and more on the depth of the our relationships week in, week out.

A summer reading list for campaigners…

I set myself a challenge at the start of the year to read a book a week – and it means I’ve got a few recommendations for those looking for a good campaigning read as they head off on holiday.

If you’re looking to dive into the lessons from successful movements of the past – I finally got around to reading ‘Bury the Chains’, which is one of the most comprehensive accounts of the abolitionist movement. It’s an absorbing read, and full of examples of how those campaigning for an end to the transatlantic slave trade use approaches and tactics that wouldn’t look out of place today.

Similarly, I really enjoyed William P Jones, March on Washington – Jobs, Freedom, and the Forgotten History of Civil Rights, for a broader look at the work that went into bringing the march together where Martin Luther King gave his ‘I Have A Dream Speech’.

If you want to understand how technology is shaping campaigning – the last 6 months have been full of stories about Facebook, data and Cambridge Analytica. So I really enjoyed ‘The People Vs Tech: How the internet is killing democracy (and how we save it)’ in which Jamie Bartlett exploration of how technology is changing democracy. It’s a quick and accessible read which isn’t full of tech-optimism, but also doesn’t leave you wanting to delete every social media account you have.

While Zeynep Tufekci’s ‘Twitter and Tear Gas: The Power and Fragility of Networked Protest’ is the best book I’ve read that explores the limits of social media when it comes to securing change. More here.

If you’re looking for some challenge on the approaches you’re taking – Then I can’t recommend ‘Where Good Ideas Come From – The Seven Patterns of Innovation’ enough. Steven Johnson has written a really interesting book drawing on the lessons from innovation across history and providing insight and tool about how to do that. I wrote more about it in a post here. I’d also add ‘Unsafe Thinking’ by Jonah Sachs to the list. More on his ideas here.

If you’re looking to be a better leader – I really enjoyed ‘The Culture Code’ by Daniel Coyle, as a primer to all the steps we can take as leaders to help team flourish, if you’re managing a team at work, or working with a team of volunteers then it’s got lots of principles you can draw from. I also found Jennifer Dulski, the former CEO of Change.org, Purposeful, a helpful read on how to be a leader in a campaigning organisation.

One of the topics I’ve been really thinking about this year is privilege in leadership, and what my role is a white straight man in helping to be a better ally. I found ‘Win Win: When Business Works for Women, It Works for Everyone’ by Joanne Lipman, a really good read for thinking about what more I can do in the office, although I prefer the books US title That’s What She Said: What Men Need to Know (and Women Need to Tell Them) about Working Together.

If you’re looking for the trend that will impact campaigning the most in the next decade– my pick of the bunch so far this year is ‘New Power: How It’s Changing The 21st Century – And Why You Need To Know’ by Jeremy Heimans and Henry Timms. It’s a book that builds on this brilliant HBR article and looks at how the nature of power is changing today, and what that means for influencers and institutions. Heimans and Timms explore how many are already harnessing New Power – if you’re looking for an accessible read with lots of practical thinking about how to succeed as a campaigner in the 21st century then it comes highly recommended.

If you’re trying to make sense of the UK today – then I’d recommend having a read of Joe Hayman’s ‘British Journey’. Hayman is a former special adviser who spent 3 months after Brexit travelling around the UK talking to people about what was behind the vote to leave. The result is a really good read on views far outside the ‘London bubble’. I’d add Ian Bremmer’s ‘Us vs Them – the failure of globalism’ if you’re looking to complement it with some more analysis of the forces driving the rise of populism.

I’m looking for recommendations for what to read over the rest of the year – so please do add thoughts to the comments below. I’m very conscious of the 12 books I’ve recommended only a quarter are by women authors, so that’s certainly something I want to address in the second half of the year.

Could 'unsafe thinking' help us come up with better campaign approaches?

I’m reading a lot at the moment – so forgive me if the next few posts are based on thoughts solely derived from the last book I’ve read.

I’ve just finished Jonah Sachs ‘Unsafe Thinking’. If you recognise the name, Sachs is the author of Winning the Story Wars, which is a brilliant read on using the power of stories to engage people to take action.

But in his latest book, he explores how we can get out of the patterns of behaviour that find ourselves following a well-trodden path in our approach to solving creative campaign problems.

I’ve come away from reading it with 8 principles to push when trying to come up with next campaign approaches and tactics.

1 – Push imagination – ’never use the same tactic twice’ is the advice from Micah White, who wrote the Adbusters manifesto that helped to launch the Occupy Movement. He contends that novelty and unexpectedness keep the public and press interested in a campaign – imagine approaching a campaign planning session where you couldn’t reuse an approach that had worked for you in the past.

2 – Push your passion – research shows that the most effective thinking can come when you’re ‘in the flow’ – when you’re working on something that you’re truly passionate about. Work to solve problems that you really believe in.

3 – Push out of the ‘expert trap’ – If you’ve ever been in a situation where you’ve been coming up with you’ll be familiar with the idea of ‘paralysis of analysis’. When you’re so much of an expert you can’t see the solution. A little knowledge about something is vital, too much and you can get entrapped, unable to see signals and information that might be telling you something different. Experts don’t always know best!

4 – Push those on the edge of the room – Sometimes we can be too close to a situation to be able to assess the best options. We find ourselves frozen by the urgency of solving a problem. Those on the outside of a room – close enough to the details but with a different perspective can be helpful.

5 – Push intelligent disobedience – some of the best solutions come from those who have a hunch that is just outside the boundaries of what’s acceptable. How can you encourage others to explore these space – it’s a tightrope to walk but this discomfort can lead to reasonable risk-taking that can lead to new approaches or innovation.

6 – Push (friendly) conflict – employ a ‘red team’ who are specifically mandated to challenge a strategy to make it stronger. It’s worked as an approach in the armed forces for decades, where everyone knows the purpose of the team is to expose flaws so they can win.

7 – Push others forward – If you’re a leader and you start a meeting sharing your opinion, chances are it could be a quick meeting, as others will often decide to agree with you. Instead stand back and encourage others to share – ask them to discuss what the group doesn’t already know. It’ll bring new thinking into your planning.

8 – Push dialogue with those you disagree with – a harder approach when campaigning is so often about identifying how to, but dialogue with those who hold opposing views can help to build new understanding and challenge blind spots in our own thinking. So often our approaches are tied to our beliefs and values – some dialogue might help to shift that.

Some of these approaches feel easier to push into than others – I can see how it’s possible to push (friendly) conflict, how you can change your management approach to push others forward or pushing imagination. While others feel harder, like dialoguing with those you disagree, but as Sachs writes in the book – pushing into the discomfort is a key element of identifying the ‘unsafe’ approach is working.

Can we stop the inevitable? Some thoughts on the theory of change behind stopping Brexit

I’ve got a campaign frustration that I need to be honest about – what is the theory of change behind the ongoing ‘stop Brexit’ campaign.

Now put aside for the moment if going back on the original referendum is a good thing, both for the public faith in democracy and if it’s legally possible, but it is one campaign that seems to have an ability to wind me up, because I can’t see anyone outline a plausible theory of change, but yet millions of pounds are clearly being spent towards it.

As I’ve written before, I don’t think that we’re going to be able to reverse the outcome of the 2016 Referendum by –

- Organising demonstrations in places that comfortably voted Remain – because it’s just making people who already voted Remain feel like they’re doing something, but that isn’t building power.

- Complaining that the BBC isn’t covering the ‘remain’ campaign – because let’s be honest they cover almost zero demonstrations.

- Moaning about the statistics the Leave campaign used – because as Nicky Hawkins points out that’s not a way to persuade people to change their minds.

So I’ve been looking at applying the 5 theories to inform policy change outlined in Pathways to Change as a working example of how Brexit could be stopped.

In doing so I’ve found it a useful way of turning what is a really brilliant, but fairly dense report into something that helps campaigners think about the different opportunities to deliver policy change.

1 – Large leaps – crisis or sudden unexpected events create the opportunity to create change. Those in power will see that ‘something has to be done’ to respond to an unexpected or unanticipated event. Too often campaigners aren’t well placed for these moments, for example, the 2008 Finacial Crisis which threw up the opportunity to push for legislation that might put more controls on the financial sector.

So for those hoping to halt Brexit what are the ‘large leap’ moments that might cause a fundamental rethink of if we should remain – have they created a ‘break glass if’ strategy ready to go if something happens? Opportunities to influence and mobilise when those moments happen they move quickly so they need to be thought about in advance.

2 – Policy Window – issues get attention when they become ‘problems’ for those in power, and they know that they have to do something to respond, for example, the impending end of the lifespan of existing nuclear power stations means that the government needs to make some decisions about the future of the UK energy mix, thus providing an ‘policy window’ for campaigners for renewable energy – however for a policy proposal to be successful it needs to be seen a technically feasible and consistent with policy maker and public values.

For those looking to stop Brexit it’s hard to apply this to stop the campaign ahead of March next year.

3 – Coalition – Policy change happens through coordinated activities amongst individuals and organisations outside of government with the same core policy beliefs. If enough people can come together they can force change, however, the magic ‘n’ number of how many people that needs to be isn’t always clear.

Key to this is about recognising that the coalitions that are most likely to be successful are those that include broad and unusual suspects, so the ‘remain’ campaign is to focus on building a coalition that isn’t just made up of those that supported the original referendum. As academic Erica Chenoweth says ‘An increase in the number and diversity of participants may signal the movement’s potential to succeed. This is particularly true if people who are not ordinarily activists begin to participate — and if various classes, ethnicities, ages, genders, geographies and other social categories are represented’ which implies a big effort is needed to mobilise and bring new people into a movement – the new approach of calling for a People’s Vote could help to achieve this.

4 – Power Elites – the power to influence policy is concentrated in the hand of a few – some people have more power than others, so influencing efforts should be focused on the few, not the many.

This feels like the approach that those who are opposing Brexit are most comfortable using, almost all of the output I see from groups like Open Britain is focused on trying to influencing MPs and Ministers, it’s a plausible strategy, but a Power Elites approach requires a really sharp thinking about where power is, and who needs to be influenced.

5 – Regime – Governments must work collectively with public and private interests to achieve its aims and outcomes – these are known as ‘regimes’ – so in the UK we have a ‘regime’ around both political parties – and they coalesce around a shared broad agenda. So those seeking influence either need to become part of the existing regime or ‘overthrow’ the existing regime and replace it with another.

Another potential approach, but with both of the main political parties supporting Brexit it’s hard to see any ‘regime’ to attach to this approach – if one of the parties could be shifted then there could be a possibility of change happening in this way.

For those interested in the theory behind this post, I’ve put together this which is a short summary for campaigners of the approaches outlined in Pathways to Change. You can read the full report here.

We need to talk about Twitter – the shortfalls of protest in an age of social media

If I had a pound for every time someone had said to me “we just need to put something on Twitter” as a response to a campaign problem, I could probably retire.

I don’t believe that somehow armchair activism can win change along – I believe to do that we need to build power in person.

But at the same time, its hard to ignore the role that Twitter has played in helping movements like #MeToo and #BlackLivesMatter to emerge, and it’s certainly the case that social media has transformed the media landscape and how ‘news’ is shared.

I’m torn about the role of social media in winning real change, and that’s before we get to questions about the oversized power that Facebook, Twitter, etc has one shaping the information we consume – a theme explored in Jamie Bartlett’s excellent The People vs Tech.

So found that I really enjoyed Zeynep Tufekci ‘Twitter and Tear Gas – The Power and Fragility of Networked Protest’. In fact, I’d go as far as saying its one of the books I’ve enjoyed reading the most in the last few months.

The book is a fascinating, authoritative and accessible academic read on how social media has changed the nature of protest, and the implications of that, both good and bad.

Unlike so many books and articles on the role of social media in campaigning, it manages to avoid just trying to reinforce the ‘slacktivism’ argument or suggesting that keyboard warriors will. It’s a critical look at how social media is changing the nature of protest for the good, but also some of the unexpected consequences – this is a good TED talk of some of the key themes.

As part of it, Zeynep argues that we need to watch out for some pitfalls that can emerge from movements and campaigns that form online but then transition into popular protest;

1 – Agility – social media can be led to movements forming around a specific ask or tactic at real speed, but that can also be their downfall as they can produce ‘tactical freezes’ which make it hard for movements to easily adjust tactics or approaches in light of changing external circumstances.

2 – Resilience – many movements that have succeeded have needed to come together over extended periods of time to collectively negotiate approaches and work together, through that, they have built ‘network internalities’ the ties that help a movement to keep going when they’re not trending on Twitter.

3 – Longevity – as part of her approach Zeynap reflects on the lessons from the civil rights movement in the US – reminding us that the bus boycott in Montgomery started by Rosa Parks, lasted for almost a year, sustained by those movement organisations which we’re able to provide practical, legal, logistical and emotional support throughout the period. When a protest is happening, the role of these groups can be key to sustain it.

4 – Infrastructure – something built from the work of a group or movement coming together to deliver a shared goal or activity. The March on Washington required a team to work together to plan every aspect of the day, from lunch boxes to sound systems – I’d recommend The March on Washington: Jobs, Freedom, and the Forgotten History of Civil Rights by William P Jones for more of a look at the details that went into making the march happen.

It was, in part, that level of detail that ensured the day was known for MLKs ‘I Have a Dream’ speech rather than anything else. While social media can help to overcome some of those challenges through collaboration platforms, movements need to have organisers at the heart who are actively thinking about this, and are able to signal that to those in power that this can’t be a movement to ignore.

5 – Negotiation – while the lack of identifiable leaders can be a real strength, allowing a movement to stay on being about an idea, not a personality. When it comes to a need to negotiate a compromise with those in power this becomes harder, as it’s not possible to identify who the ‘leaders’ are. In some situations, negotiation isn’t an option, but in others, the energy of a protest disputes before any gains can be made due to the lack of its ability to collectively negotiate.

As campaigners, I found the themes really resonate at helping to explain both the tremendous opportunity that social media brings, but some of the shortcomings we need to be aware of.

It’s also reminder that change can’t be achieved by just trying capture the next ‘viral’ moment but instead requires investment in the slow and long work of building power, and a challenge to more formal/traditional actors in a movement to consider the role they can be playing in helping to build the infrastructure needed for movements to thrive.

Why the 'general public' isn't an audience for your campaign

I’m on a train heading back from Birmingham where I’ve been sitting in on some focus groups that we’ve been running.

It’s been literally the most interesting few hours of my week, and I’d recommend to any campaigner that they get themselves in to view a focus group (or do their own impromptu research in the street) on occasion because it’s brilliant.

But sitting in the groups also got me to think about how as campaigners we approach audiences, it’s a theme that I picked up when I shared at the NCVO Certificate in Campaigning just before Christmas, and I thought it useful to share a few different ways I’ve been thinking about audiences.

To start with, we need to stop thinking that the ‘general public’ as an audience. It’s something I hear campaigners talk about but its such a massive audience it’s – even at election time the parties don’t target the ‘general public’ because not everyone can vote, so they’re working with a narrower audience than the public.

Instead, we need to start to think about audience in the context of what our strategy tells us that we need to achieve, and focus on who we need to be engaging, mobilising or shifting the attitudes.

Thinking about it that way and you can start to cut your audiences in a range of different ways – here is a quick guide to get you started with some common approaches;

Geographical – based on the location of your audiences, it might be that you decide that specific parliamentary constituencies are going to be important for your campaign, so you want to focus on those who live in a number of key seats. Incidentally this recent NFP Synergy research of what influences MPs highlights again the importance of smart geographical targetting as a way of building relationships in Parliament

Political Influence – this can be as narrow as those that are likely to vote for a specific political party, but it can also be the groups of the population that parties want to appeal to as they seek to win votes and support. In recent years, that means considering focusing on certain demographic groups that the parties have competing to reach, like the JAMs (Just About Managing) or ‘squeezed middle’ from recent years, or Mondeo Man or Worcester Women

Attitudes – Depending on what you’re looking to achieve, you might want to focus on the attitudes that different audiences hold on a specific issue. For example, on overseas aid, you could categorise people as supportive, swings or sceptics. On this, the risk can be that it’s very easy to spend lots of energy on either energising those that are already supportive or getting worried about the sceptics, but the value is often in focusing on the swings.

Behavioural – if you’re campaign is about volume then focusing on behaviours can be a good place to start, if you can find a way of energising existing activists then that can be an effective way of growing numbers, but again the pitfall here can be that you can end up risk preaching to an existing choir to the detriment of presenting wider support for your campaign.

Values – there has been lots written in recent years about starting with the values and beliefs that people hold. Chris Rose writes about the role of pioneers, prospectors and settlers in his work on campaigning audiences, while Common Cause has approached this through the lens of frames + values. This isn’t always the easiest approach to get your head around, but it can be valuable for thinking more deeply about your audience.

Economic – I’m not sure that campaigners spend enough time thinking about possible economic audiences, but there can be a real influence in mobilising the grey, purple or pink £s or focusing on those who hold shares or investment in a specific company, something that Share Action do brilliantly.

I’d love to know what you are thinking about when you approach thinking about audiences for your campaign.