Last month I shared a few thoughts about what issue campaigner can learn from party political campaigning.

A few people encouraged me to do the opposite post, but as I started writing I discovered this isn’t really lessons for political parties from campaigning organisations, it’s more my reflections from 5 years as a volunteer campaign organiser within the Labour Party.

Some caveats to start with. My experience is perhaps an isolated one, I’ve been focused on working in support of one party in a few constituencies in SW London, and I can’t say that I’ve managed to address everything I’ve written in the constituency I was involved in, but they’re a few observations, which feel timely as the Labour Party considers its future direction.

I’ve tried to avoid too much of a focus on the idea that too many party members are focused on the minutes of the last meeting, that we send too many emails (which we do!) or we only visit at election time (which we don’t).

Why? Yes, it’s sometimes true we do all those thing but it’s also an unfair parody. Many of those I’ve worked alongside have been committed, dedicated individuals who put in hours of volunteer time determined to make a difference in their community. Instead I’ve chosen to reflect on the following.

1. Don’t forget to evaluate – I’ve been through a number of election campaigns now, they’re all different, but in all of them I’ve spotted things I’d do the same or do differently. It’s surprised me that the political parties don’t have a instinctive or systematic approach to sitting down, evaluating the evidence and learning what’s worked and what hasn’t.

Perhaps its because politics is always moving along, win and you’re into governing. Lose and the last thing you want to do is reflect on what you did wrong, but it’s a practice that needs to be encouraged at all levels of the party. Personally, despite feeling numb from the result of the election in May, I’m glad the Labour Party has committed to do a full review of what worked and didn’t work, and it’s great to see some of the candidates do the same. That needs to become the norm not the exception, and the findings need to be distributed widely.

2. Test, trial and try new – Elections are in many ways won (or lost) using the same formula that parties have been using for years. Yes, there are a few examples of doing differently (Birmingham Edgbaston is the example that was rightly praised in 2010 and Ilford North in 2015) but outside a few campaigns committed to pioneering , and the work of the Labour digital team who I think awesome, new approaches seem to be to too often few are far between and not mainstreamed quickly.

Innovation is hard when the risk of it not working is losing an election, and not all campaigning organisations get this right either. But I’d love to see the party embrace a culture of testing different approaches to see what has the biggest impact, trailing something new, building an evidence base based on experimentation.

It doesn’t mean throwing the old playbook out (there is much to be said for the approach of going door to door and being routed in a community) but the playbook needs to have some (evidence-based) chapters added to it.The experience of Arnie Graf and the suspicion with which his community organising approach was viewed is a lesson in how hard this can be.

3. Share learning – In the overall scheme of things I was a fairly unimportant volunteer. But with a (unhealthy) passion for campaigning that took me to the US to learn how Obama did it in 2012, I was amazed at how little learning and good practice is proactively shared amongst other volunteer campaign organisers. I’m sure there is loads I could learn from others across the UK, but I found more ideas from reading books and blogs about what was happening in the US than I did others in the UK.

The Labour Party would do well to emulate a model similar to that of the Analyst Institute in the US and build a closed community committed to share evidence and best practice for paid staff and key volunteers (like me). But learning shouldn’t be limited from within the Party, since the election its been more interesting reading learning from Conservative activists, like any good campaign the party needs to be open to collecting ideas for a range of sources.

4. Remember the pyramid of engagement – A graph like the one below should go up in every Labour Party office. Sure some really skilled professional people just love to deliver leaflets (I’m one of them now – it’s good exercise) but too often that’s all we ask them to do, just knock on doors or deliver leaflets.

The pyramid of engagement is a tool well know to campaigners, all about how you help you develop a plan to recruit individuals and engage individuals. Some constituencies do this really well, but sadly most don’t meaning talent is wasted or under-utilised.

5. Invest in your people – The Labour Party relies on a small army of organisers in many of its constituencies, most are recent graduates paid too little, and asked to make huge sacrifices of time in the run up to an election. Some are stick around for year, but most drift away after an election or two. That’s valuable institutional knowledge walking, and a huge cost in training new staff.

We don’t have the culture in the UK of a professionalised political campaign staff, but as a result there a few incentives for the most effective organisers to stick around, the training they get seems to be patchy and the support/supervision from more experienced staff limited. Building a clear career pathway that rewards the most effective rather than those who have the most stamina, and effectively scales to provide the right level of support and supervision is needed if we’re to build a cadre of brilliant campaign managers.

6. Build a culture of accountability – At times, asking how another constituency how many contacts it’s made is similar to asking someone else how much they get paid. It’s shared with reluctance and is probably over or under inflated! Work needs to be done to ensure the metrics are more sophisticated than simply the number of contact made, although that’s still an important benchmark of activity, to ensure they’re capturing volunteer engagement and much more.

But those figures need to be shared and scrutinised. To my mind it’s unacceptable that we don’t have a culture where one constituency can benchmark itself against another and those who aren’t performing, including where we have longstanding MPs, are called out by the National Executive Committee or another representative body.

So a few lessons from me. As I was writing this I re-read parts of Refounding Labour. It’s a document full of practical recommendations. It would be easy for whomever becomes leader in September to bin it, as a holdover from the previous leadership, in my opinion that would be a mistake.

Get my latest posts sent directly to your inbox – sign up here.

Author: mrtombaker

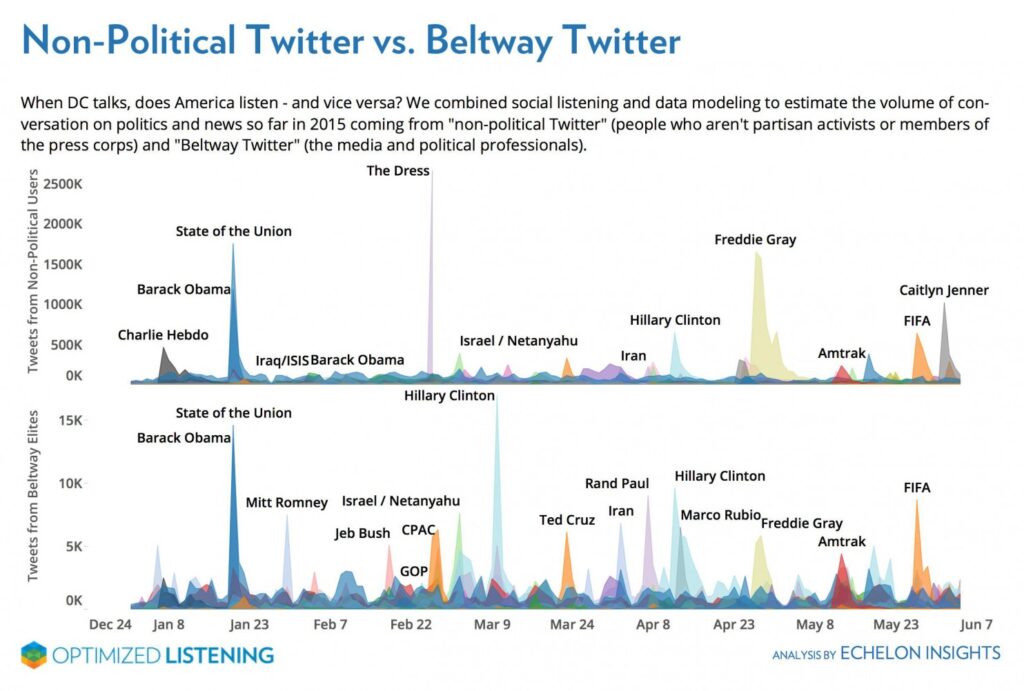

Beware the Twitter echo chamber – Graph of the Week

One Direction (don’t pretend you don’t know who they are!) supported the Action/2015 campaign a few weeks ago. The engagement on Twitter was amazing, I’ve never seen so many RTs so quickly but you didn’t see any of that action on my Twitter feed (follow me at @MrTomBaker).

That experience and this article on the role of social media in people thinking that Labour would win the election got me thinking about how Twitter is a big echo chamber with lots of political people talking to each other but often few campaign cutting through beyond that.

I’ve not seen any similar research from this side of the Atlantic, but this graphic, which looks at what those inside D.C. Beltways (the US equivalent of the Westminster bubble) posts on Twitter versus what everybody else in the US posts on Twitter is instructive.

Five for Friday – Winning the support needed

I’ve been thinking a lot over the last few weeks about the importance of starting with the audiences you need to win, rather than the activists we already have.

So this Five For Friday is a collection of articles that have helped my thinking in the last few weeks;

1 – Kirsty McNeill on the difference between ‘people power’ and ‘activist power’ and the importance of understanding that difference.

2 – How the Equal Marriage campaigners in the US realised they needed to change the framing of the message (and the 10 lessons from the campaign)

3 – I’ve shared this before, but Roger Harding on how Shelter moved housing up the agenda is a must read for all campaigners.

4 – 10 years on from Make Poverty History, here are some reflections from the lessons of a campaign that got 90% brand recognition from Kirsty (again!) and my colleague Alice Delemare.

5 – More insight from how the Conservatives did this so well in the last election by ruthlessly focus on the people who matter.

10 years later – some personal reflections on Make Poverty History

2005 was a good year, I got engaged, England finally beat the Aussies to win the Ashes, and I got to work on the Make Poverty History campaign.

Make Poverty History was the first big campaign that I’d be paid to work on. It was a huge movement that mobilised 100,000s of people to take action on debt, aid and trade as the UK government hosted both the G7 and the EU Presidency.

This week, its a decade since the biggest moment of the campaign, a huge 250,000 person march in the centre of Edinburgh, accompanied by the Live 8 concerts on the eve of G7 leaders meeting in Scotland.

10 years later, and it’s still the campaign that I mention when I try to explain what I do to my second aunt.

While lots has been written about the impact of the campaign, being the first campaign that I was really involved in organising I’ve been reflecting on the campaigning lessons that Make Poverty History taught me. There are lessons that still apply today;

1. Unusual coalitions deliver change – at the time, I remember a friend who worked in a totally unrelated job at Number 10 talking about how the unexpected partnerships around the table the campaign was creating waves internally. Bringing together 500+ organisations meant that the campaign couldn’t be dismissed as just ‘the usual suspects’.

2. Be prepared for the second act – I’ve written about this before, but the campaign ran for the whole of 2005, concluding in a Mass Lobby of Parliament in the rain on trade justice in November, but because the majority of the resources had been deployed to ensure the push towards the G7 moment was as successful as it needed to be, the campaign didn’t have the resources for the ‘second act’ causing a loss in momentum over the summer, and the impression by some that the campaign had come to an end.

3. Sometimes you need to let it go – I remember that it quickly became apparent that the campaign had captured the public imagination, individuals were calling up with , events being organised across the country, churches want to wrap their spire in WhiteBands (the symbol of the campaign) and much more.

Now we’ve become very used to the idea of more decentralised ‘bottom up’ campaigning, an approach pursued by groups like 38 Degrees, but at the time it was uncomfortable for organisations who’d been used to a more ‘command and control’ approach to managing their campaigns. If our campaigns are to come to life we have to be prepared to let the brand run a little wider than we’d immediately feel comfortable.

4. A good campaign has a halo effect on its targets – most of the MPs who were lobbied as part of the campaign probably can’t remember the details of the policy asks from the time, but the impact of the campaign have lasted well beyond 2005. Long after the campaign has come to an end politicians who were lobbied still mention Make Poverty History. As we get further away from 2005, that effect is definitely declining, but even today I think we’re getting wins on international development issues as a result of the campaign.

5. A campaign can benefit from a ‘radical flank’ – the tensions within the campaign, between organisations who had different political and policy analysis have been written about elsewhere, but the campaign was a excellent examples of the concept of the ‘radical flank’ when the positive or negative effects that radical activists for a cause have on more moderate activists for the same cause. Did those groups who took more ‘radical’ position help mean that the asks of the campaign were seen as more ‘moderate’ by the government and thus achieved?

6. The transaction costs of building coalitions are high – Make Poverty History was over a year in the making before it was launched in early 2005, it took many hours of meetings and discussions to reach agreement, a reminder that the start-up costs of forming coalitions are often significant. This work was helped by a tradition of working together that had come from previous campaigns on debt and trade by many of the key organisations, the need to keep this type of infrastructure in place is vital to build trust and bring individuals and organisations together.

7. Building public support is really hard – Make Poverty History had a brand recognition of 90%, but despite all the high profile media, celebrity involvement and grassroots chatter, the evidence suggests that it didn’t lead to a significant increase in the number of people ‘very concerned’ about global poverty issues. It’s a reminder that building public support requires sustained attention (and perhaps using the right frames).

8. Don’t be afraid to try something new – The campaign adopted this approach ‘“don’t be afraid to be the first to ‘crack’ a new platform, give trendy a try, and take a risk!”. In many ways Make Poverty History was the first internet campaign, albeit one with a campaign video where you had to select the speed of your dial up connection, comfortable trying out new approaches as we sought to understand the power of the web for campaigning.

Looking back, I’m incredibly proud of the small role I played in the Make Poverty History campaign, it wasn’t a perfect campaign (here is a secret – no campaign is) but one that taught me so much but more importantly delivered real results.

I’ll take the memories of Vicars walking to Downing Street, Nelson Mandela in Trafalgar Square, getting sunburnt in Edinburgh, staying up all night on Whitehall, and getting very wet outside Parliament wherever I go in my campaigning career. It was a very special year.

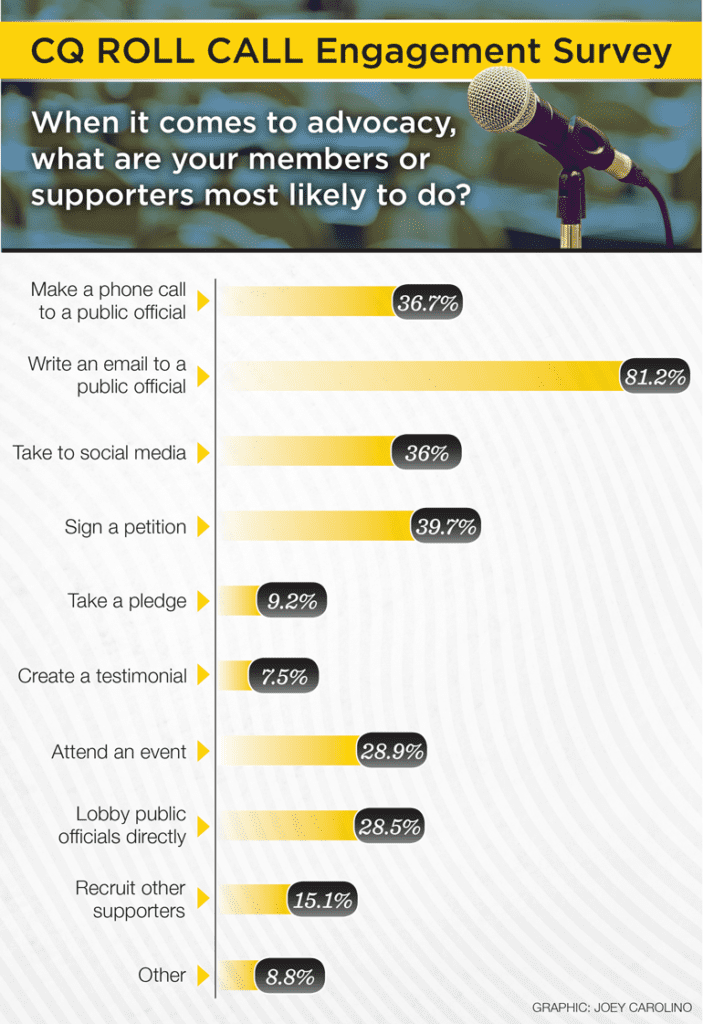

What advocacy actions are your supporters most likely to take? Graph of the Week

An occasional series of fortnightly posts with useful graphs for campaigners.

Spotted this in the very useful Connectivity blog. It’s from the US, but I suspect the results would be similar in the UK.

The findings came out at the same time as the results of the annual Benchmarks survey, which pulls in insight from 84 advocacy organisations, and found that;

- More people are opening advocacy emails. Advocacy open rates in 2014 were 16% — that’s 9% higher than the same organisations saw in 2013.

- Fewer people are taking action. For every 1,000 advocacy emails an organization sent, they generated 29 actions (we’re talking basic fill-out-a-form stuff like petitions and letters to Congress). That’s down 18% from the same organisations’ response rates in 2013.

Some useful food for thought as we consider who we get supporters to take the most effective actions to take.

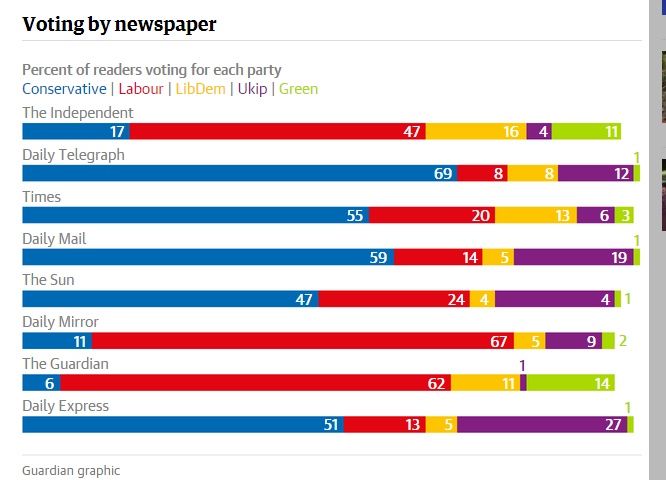

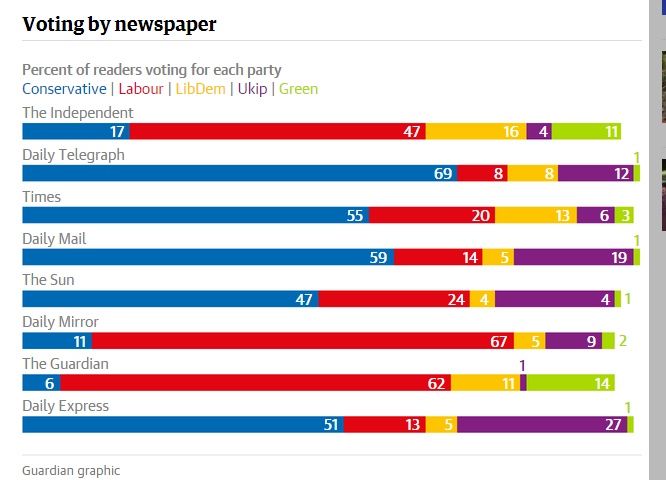

Which newspapers really matter for campaigning – Graph of the Week

The first in an occasional series of fortnightly posts with useful graphs for campaigners.

Campaigners spend lots of time looking to get media coverage for their issue. This graph is a good reminder of the political allegiances of the readers of each paper, providing useful insight into which papers are most important for the political parties.

It also broadly matches the parties they endorsed at the last election – the UKIP backing Express, and Conservative backing Independent are the only papers that backed a party different from the majority of its readership.

So if you want the Conservative government to back your campaign it can help to get coverage in The Sun rather than the Mirror, the Times rather than the Independent.

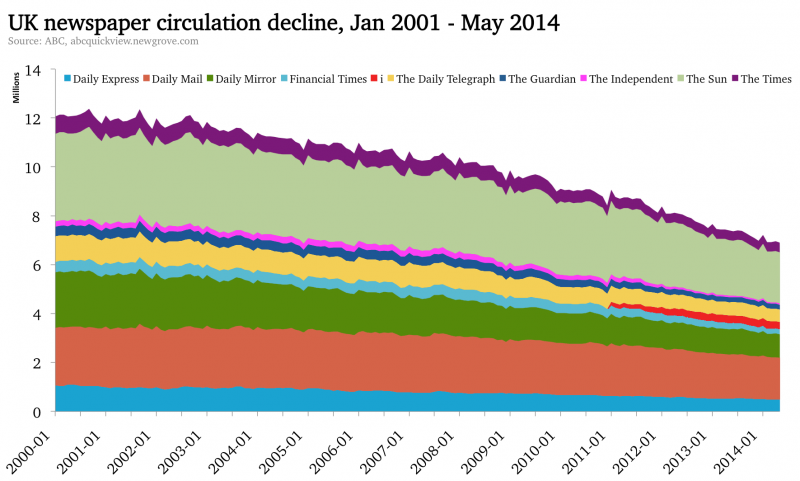

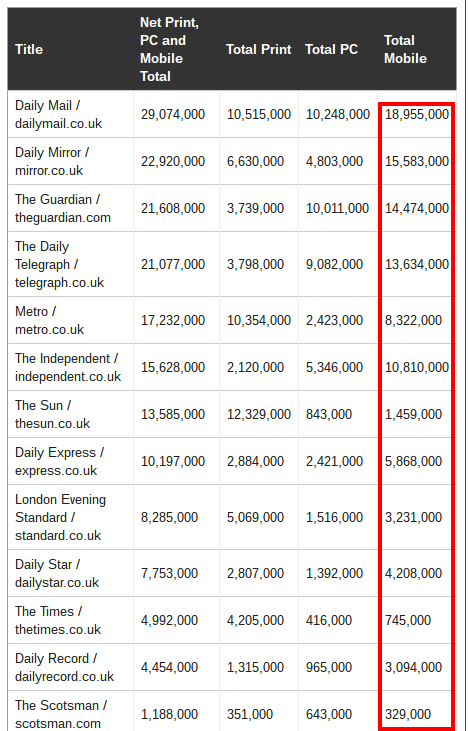

It useful to also to be viewed in conjunction with this graph, which shows the decline in readership,

This table which shows the readership changes when you take into account the online and mobile readership.

Either way, given its the papers that it suggests if we want to be setting the agenda with our government then as as campaigners we should spend more time reading The Sun, Daily Mail or Telegraph, and less time with the more familiar Guardian.

What 5 years of door knocking has taught me – lessons from party political campaigning

Last night I stood down as Vice Chair – Campaigns for Tooting Labour Party, don’t worry this isn’t a long post about why Labour lost, but for the last five years I’ve been juggling being a campaigner by day, and a volunteer campaigner by night (and weekend!).

Some have suggested that charity workers shouldn’t be active members of political parties. It’s not a position that I agree with.

I think we want to see campaigners involved in a range of parties (as they already are), but begin involved in the Labour Party have made me a much better campaigner.

Here is how. It’s reminded me that;

1 – Most of the public really aren’t interested – Earlier in the year, I saw a stat from Jim Messina, the US election campaign, saying that between November and Election Day the average member of the UK public would spend just 104 minutes thinking about the election. I’m not sure of the accuracy of the statistic, but spend the weekend knocking on a few doors and you’ll know what he means. Most people aren’t that interested. I’ve often thought about how the message of my daytime campaigning will play on the doorsteps of floating voters in Tooting. How do I explain my issue in the snatched conversation before they’ll politely ask if they can get on with the rest of their day!

2 – All politics is local – It’s a cliche, but it’s true. Ask people what the issues or concerns are and they’ll probably tell you about the flytipping down the street or the like. Run a campaign to save a local pub, or make your road 20mph and it’ll be hit. If you’re writing camping literature you want to know what the impact is on the constituency or better still the ward. Campaigners who can provide that level of detail are setting themselves up for success (take for example this smart campaign from Shelter that does that).

3 – See politics up close – I’ve not worked for an MP, so being involved in a political party has provided me with an insight about the multiple demands on a MP or Councillor. How different groups and organisations can position themselves effectively to demonstrate support. How politics at all levels is about trade-offs and being much clear who your opponents are than is often the case in international development campaigning. It’s given me a living template for my power analysis.

4 – Volunteers matter – Obvious perhaps, but a local political parties like many campaigns rely on the dedication and commitment of an army of volunteers. Volunteers who need to be motivated, listened to, thanked, encouraged and inspired. Make it easy and enjoyable, they’ll come back and get more involved. You can never invest enough in your grassroots.

5 – Test and trial – when it comes to winning elections every vote matters, so I’ve spent hours trying to engage in the huge body of research and evidence about how to do that better. From how to increase turnout from irregular voters to targeting your messaging someone has done a study on it. I’ve written before (here and here) about how campaigners should look to elections campaigns for example of the best practice that often end up being used in our campaigning. The US presidential election is the pre-eminent example of this, but lots of good ideas come out of the UK General Election as well. Campaigners would do well to read the articles on Labour List, Conservative Home and elsewhere about worked and didn’t work ahead of 7th May.

6 – You need to do offline and online together – like many campaigns, political parties have become enthralled by the power of social media to engage voters and volunteers. It’s lead to some awesome content and ideas, but the evidences suggests its still only effective when combined with an effective ground game. The individuals who are prepared to knock on doors or organise in their communities. Campaigns that combine the two together do the best.

7 – Change can happen – Working in international development is my passion, but change can sometimes feels like it can take a long time to come, and the impact even longer (and further away), so being involved in local politics has helped to keep my thirst for change high.

Who are the best messengers for our campaigns?

A study out recently suggested that people could be persuaded to change their attitudes to same-sex marriage as the result of a 22 minute conversation with a gay canvasser.

It’s the type of research any issue campaigner is fascinated by. How to win someone over to support your argument.

Sadly those particular research findings have been discredited, but it got me thinking what does the evidence say about who the most effective individuals we can use to persuade audiences to support our campaign.

Here are a few studies I’ve come across;

- People are persuaded by people like them. Studies of field organising in election campaign has shown that if you want canvassers similar to the target population your trying to reach, I suspect that their is something in this for all those looking to persuade.

- The public have high levels of trust in academics and experts. They consistently perform well as the most trusted spokesperson in the Edelman Trust Barometer (incidentally in the study, NGO spokespeople also perform well, but those figures are dropping).

- Celebrities have a mixed impact. They don’t have the affect that you’d expect amongst the general public, although when asked the public think that they’ll be effective at persuading others, but they can be effective at gaining access to decision makers who believe they represent public sentiment.

- Change.org have proven the power of the personal stories of their petition starters, while the personal testimony to engage action is at the heart of the community organising approach of Citizens UK. The Story of Self, Us and Now is a effective tool to use, because research shows the human brain has a natural affinity for remembering facts and statistics when presented in a narrative construction (a story to you and me!).

- Whoever says it, make sure they say it again, and again and again. Its an age old adage from the marketing industry, but a good reminder to campaigners who get bored of the same message quickly. Those working on housing issues found it took a year of repeating and repeating the same core message to see the polling move.

This is my short list of studies, but please do use the comments box below to add others you know about.

Under Threat – 4 challenges to charities speaking out

I’m still digesting the full implications of the election results, but one (of the many) areas that I’m concerned about, is the space that charities and NGOs will have to speak out under the new government.

Remember those quotes about how charities should ‘stick to the knitting’, well that view just got more prominent in Government.

Now you might expect me to be an advocate for the importance of charities campaigning and I am. But looking across history I can see numerous example of how charities and NGOs have come together to push for change, as Ed Miliband rather eloquently put it during the election campaign;

And that’s the way change has always happened. Through people.

100 years ago, the trade unions joined together and campaigned for workers’ rights and they won.

70 years ago, the working people of our country joined together and campaigned for an NHS and they won.

40 years ago, working women joined together and campaigned to legislate for the principle of equal pay and they won.

20 years ago, the gay and lesbian community of our country joined together and campaigned for equality in law and they won.

And in all these movements and moments, when people asked who will fight this fight? They didn’t wait. They didn’t say it was up to someone else. They said “call on me”.

But one thing that could change over the next 5 years could be the space that charities and NGOs have to campaign. So what are the actual threats? Here are 4 potential challenges that every campaigner here in the UK needs to be concerned about.

1. Adjusting to the Lobbying Act – it’s now highly unlikely to be repealed and while Lord Hodgson is undertaking a review for the government of its impact (something we got thanks for campaigning) which could lead to some small changes, but the Lobbying Act is here to stay and we’ll need to adjust to it in future elections.

2. Reviewing CC9 – this is an important but little known piece of guidance that allows charities to campaign when they’re doing so in line with their charitable purpose. While the exact timetable is yet to be announced, expect it to happen in the next 12 months and don’t expect it to be a review that expands the space we have to campaign. This is going to be a critical fight.

3. Paying to protest – before the election, campaigners saw off a push from the Metropolitan Police to charge climate change campaigner to pay for the policing a peaceful march they were organising in Westminster. With further pressure on police budgets, expect to see the Police push this again. I’ve already heard of at least one event this could effect. While their are massive pressures on police budgets, it’d be a worrying precedent if we’re expected to pay to protest. With the London elections coming up, we need to be pushing for all the candidates to agree that the Metropolitan Police shouldn’t charge us for our right to protest.

4. Reporting on a charity’s total expenditure on campaigning activities – this was consulted on by the Charity Commission last year but they decided not to pursue it. Expect it to come back again, and while it might seem little like a small issue compared to the others above, my concern is that it could a) lead us to a situation like that in Canada where charities can only spend up to 10% of their income on campaigning activities and b) would mean charities have to spend more time to monitor this, potentially putting off smaller organisations from getting involved in advocacy, as they simply don’t have the capacity .

So what can be done about it?

- Become aware – all these threats are happening around us, become aware of them and start to think about the possible implications for your campaigning. If your on a board of an organisation that campaigns you want to be thinking about what these changes could mean for your organisation.

- Organise – campaigns are forming to respond to many of these challenge, and we know this works because it was thanks to campaigning on the Lobbying Act that we got some important concessions. Campaigners from a vast range of organisations need to get involved, campaigning on these issues, but its a classic example of a tragedy of the commons, we’re all affected by the changes but its not in any single organisations interest to campaign to stop the changes. If you in London, come along to this meeting on Monday 1st June to find out more about how we can organise together.

- Be prepared to stand in solidarity – not every campaigning organisation will affected by these changes. If you don’t organise marches, parliamentary lobbies or demonstrations you might not be concerned about pay to protest, but it’s the precedent that should concern us all. First it’s protests, but what next? Hand-ins? Parlimentary petitions? We need solidarity between campaigners on these issues, like we saw last year when concerns were raised about a tweet from Oxfam that led to 70 organisations signing onto a letter in The Times.

Five for Friday – Post-Election Special

The election might be old(ish) news, but the last week has generated some useful reading for campaigners.

1 – A wise campaigner learns from those who win. The Guardian has a exclusive video of Lynton Crosby sharing his insights, while the Spectator profiles the approach of American Jim Messina.

2 – Chris Rose has been here before, he shares his reflections on what campaigners should prepare to do next.

3 – Jim Coe asks if the election raises some more strategic questions for campaigners.

4 – Chloe Staples at NCVO has two brilliant posts on working with the new Parliament and new MPs, plus tips from the former MP for High Peak.

5 – Housing has raced up the political agenda over the last 5 years. Roger Harding shares some lessons from Shelter.

Feel free to post great post-election reads in the comment section below, and if you missed it, my thoughts are here.