It’s the time of year when people are looking for ideas for Christmas gifts. So here are a few recommendations from things I’ve read over the last 12 months for campaigners looking to add something else to under the tree.

How Change Happens – Duncan Green’s long trailed book answers a critical question that all campaigners need to grapple with – how does change happen. It’s a really good read, and as I wrote here I really enjoyed some of the challenges that Duncan puts out to those of us who work in campaigning. Change doesn’t happen in a linear way, and we need to adjust our thinking and approach to respond to this.

Rules for Revolutionaries: How Big Organizing Can Change Everything – I need to do a bulk purchase of this to pass onto my team. It’s simply a brilliant book written by Becky Bond and Zack Exley who were the brains behind the ‘distributed organising approach’ that took Bernie Sanders so far in the Democratic primary in the US .

Rules for Revolutionaries: How Big Organizing Can Change Everything – I need to do a bulk purchase of this to pass onto my team. It’s simply a brilliant book written by Becky Bond and Zack Exley who were the brains behind the ‘distributed organising approach’ that took Bernie Sanders so far in the Democratic primary in the US .

It’s short, at around 150 pages, unpacking how the approach was so successful with lots of stories to make the pages wizz by. Bernie Sanders clearly built something very unique so the 22 rules in this book. It’s oozing with wisdom and insight. A MUST READ.

Blueprint for Revolution – I loved this from Srdja Popvic, the Serbian activist who led the movement to overthrow Slobodan Milošević and has shared his skills around the world since. It’s part autobiography, but also part playbook for anyone involved in campaigning. It’s an easy and enjoyable read, with Popvic mixing a range of stories from his personal experience with lessons from history. My review of the book is here.

The Inevitable – this isn’t a book about campaigning, but the themes that Kevin Kelly explores in his book which looks at the themes which will shape technology over the next 30 years are totally relevant to anyone who wants to. I put the book down feeling a mixture of emotions, excited about what the future will look like for campaigning but also daunted about what the trends driving us towards. This is one of the best books I’ve come across to looking into the future. It’s not an easy read but a worthwhile read.

Ireland says Yes: The Inside Story of How the Vote for Marriage Equality Was Won – I had the privilege of hosting Gráinne Healy at the Bond Conference in March. Her insider account of the campaign for equal marriage in Ireland is brilliant.

Ireland says Yes: The Inside Story of How the Vote for Marriage Equality Was Won – I had the privilege of hosting Gráinne Healy at the Bond Conference in March. Her insider account of the campaign for equal marriage in Ireland is brilliant.

As I said to CharityComms – it’s a page-turning account of a referendum campaign which successfully integrated brilliant messaging, powerful messengers and creative tactics to win.

If the story of the Irish referendum inspires you, I’d also really recommend Winning Marriage: The Inside Story of How Same-Sex Couples Took on the Politicians and Pundit sand Won which focuses on the equal marriage campaign in the US.

Looking ahead, I’m also super excited about 2 books coming out in early 2017. The Myth Gap: What Happens When Evidence and Arguments Aren’t Enough by Alex Evans and Analytic Activism: Digital Listening and the New Political Strategy by David Karpf.

They’re definitely on my wish list for early 2017. What else should I be adding?

Looking ahead – some questions for campaigners

Back in 2014, at the start of my time at Bond I wrote this post on the 4 trends driving campaigns. I was trying to reflect on the big themes that I anticipated would shape campaigning for the networks members (and beyond) in the coming years.

I finished at Bond last week, as I’m moving on to lead the Mobilisation Team at Save the Children UK – I can’t wait to get started working with the team to continue to build a movement to speak out vital issues like child refugees, Yemen and early years education in the UK.

(It’ll also mean that I’ll be putting a pause of blogging until after Christmas so I can focus my energies of getting settled into my new role – but that’s the housekeeping notices out of the way!)

But as I finish my time at Bond after 2+ years, I’ve been reflecting back on those trends – I think they’re all still relevant for campaigning organisations to grapple with – but I’ve also been struck that there are some core questions that campaigns teams need to be discussing.

They’re drawn from some of the articles and reports I’ve been reading, and conversations I’ve been fortunate to have with campaign leaders from the UK and beyond over the last few months.

1. Is our approach Managerial or Networked?

Managerial campaigns are more centralised and controlled. With that can come the opportunities to deliver big ‘set piece’ moment, but managerial campaigns can struggle to respond with the agility that can be expected in the age of instant communications.

Networked campaigns are distributed – they haven’t necessarily given away all control, for example overall political strategy might be held at the centre, but much decision making is pushed downwards, and their is autonomy to decide what is most appropriate at a local level.

Much of my thinking of this is drawn from the Networked Change report I wrote about here.

2. Are we focusing on Mobilising or Organising?

Mobilising is building membership and focusing on maximising the number of actions that can be taken. It can be an effective at demonstrating breadth of support, but can lead to a constant need to invest in recruiting.

Organising is about focusing on building power and leadership with communities. Demonstrating depth of support and building leaders who can engage others.

Much of my thinking here is drawn from the work of Hahrie Han who I help to host when she visited London in March – helpfully summarised by Jim Coe here.

3. Do we have Convening Power or Organising Power?

Convening power is the ability to leverage identity and networks to bring leaders together- for example the ability to get lots of senior leaders to sign onto a letter or a range of organisation to ‘back’ your campaign.

Mobilising power is being able to draw on a base of supporters to back your policy demands and willing to engage in conflict with organised opposition – the ability to bring people out to actively support your issue.

My thinking on this is drawn from a fascinating set of essays on New Models of Change from a US based think-tank New America. This case study on the involvement of US evangelicals in pushing climate legislation is a perfect example of what happens if you only have convening power.

4. Are we just harnessing ‘Stop Energy’ or ‘Go Energy’?

Stop Energy is the ability to use tools to channel ‘moment-specific opposition, expressions of dissent, reaction’ on a topic or issue. It’s something lots of campaigns are effective at doing, you see it in emails asking you to ‘sign the petition to stop this event happening’ for example.

Go Energy is the ability to use tools to help people work towards a ‘strategic action over time’ to help people to organise towards a particular goal or outcome.

My thinking on this was prompted by this essay from Kathryn Perera, which draws on the work of Micah Sifry.

5. Do we lead with facts or stories?

Sharing facts is what many campaigns are comfortable with doing, but we all know that they’re rarely the thing that effectively shifts peoples opinions. As this post on Grammar Schools reminds us we can have all the evidence proving that they increase inequality but that doesn’t appear to shift public opinion.

Stories and narratives can be powerful at motivating ongoing action, especially when they place those at the grassroots at the centre of the action, as Jonah Sachs says making them the heroes of what’s happening.

My thinking on this has been provoked by reflecting on the different approaches of the Remain and Leave campaigns during the Brexit vote.

6. Are we recognising we are interconnected to other issues?

Being interconnected recognises that we are campaigning in a complex environment, acknowledging and providing solidarity with that the issues you’re working on are linked to other causes.

My thinking of this was prompted by the findings of Networked Change and seeing how many environmental organisations have been actively expressing solidarity with those campaigning for racial justice, but with Brexit and the election of Donald Trump it seems even more important than before.

Email your MP – where next?

It’s a truth, almost universally acknowledged, that MPs don’t like ‘email your MP’ petitions.Listen to MPs talk to campaigners, and they’ll tell you they find the annoying and a burden on precious staff time, but they’re a staple in most campaigning toolkits.

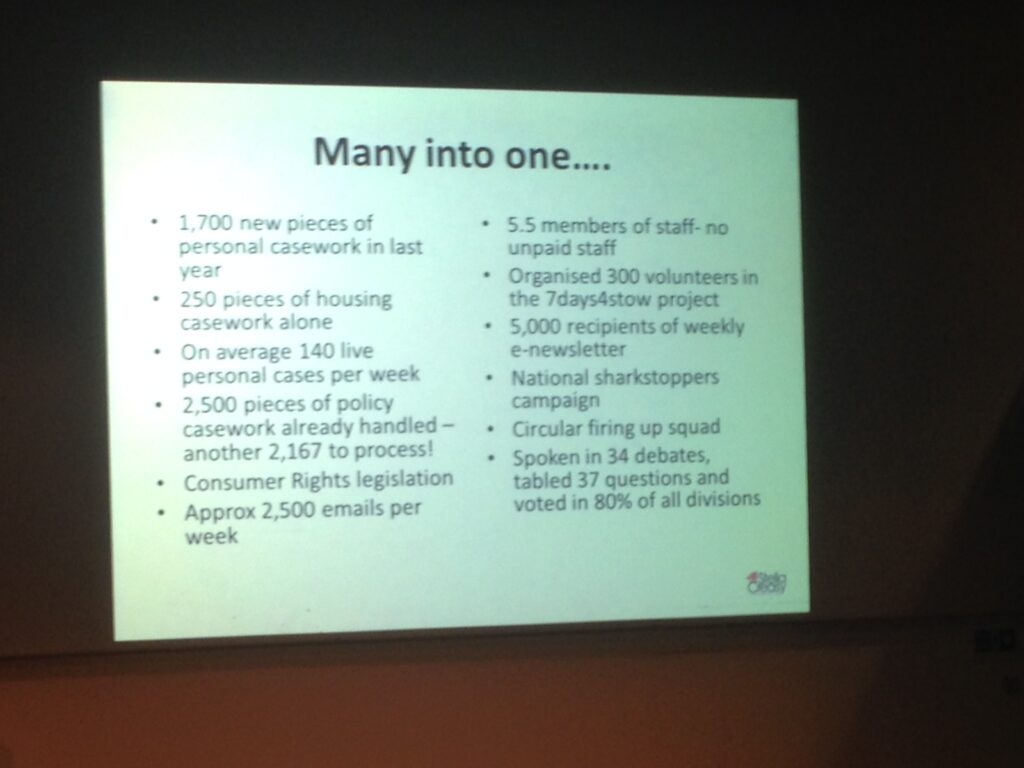

Most MPs will tell you that the volume of emails means it can be hard to distinguished between the signal and the noise? Don’t believe that? While this image is a little out of date (it’s from ECF2014) it was Stella Creasy sharing what, on average, comes into her inbox during a week in Parliament;

Now, I’m not suggesting that we should head calls from some MPs to stop petitioning them – they’re our elected officials so we should petition them. I’m also realistic that any ‘cross Parliament’ solution is unlikely to be adopted – MPs they say, have to be seen as 650 small businesses, so rarely do they all-adopt the same technology, unless they’re told to.

Plus I’m not going to dive into a debate about the quality of some campaigns, except to add that some email to MP campaigns don’t appear to have thought about what the theory of change is – and that has an impact all of us (all campaigners should read this on what makes an effective petition).

So what could replace them in our toolkit? Or if not replace improve how we use them?

1. Phone calls – Unlike the United States we don’t have much of a culture of calling your elected official – perhaps it’ll catch on? Even then it will still be likely to frustrate MPs as much as emails do as they don’t have the staff capacity to deal with the calls, or effective mechanisms to collect the information from them.

2. Parliament petition site – I’ve suggested before that the frustration of MPs could be channelled towards suggesting that they’ll only accept petitions via the official Parliament petition site. While the site has been improved, it still has lots of limitations – not least when it comes to supporter data which is held just by Parliament, that it’s a closed site (so it can’t be embedded on another website) and doesn’t allow for any personalisation by the signer.

3. Focus on a specific MP rather than all MPs – At the NCVO Campaigning Conference, Jess Phillips MP suggested that one of the most effective petitions she’d seen during her time in Parliament had been the change.org petition on the Tampon Tax, which had worked directly with Paula Sherriff MP to help to provide her with the evidence of support for the issue. Strikes me that most issues can find a Parliamentary champion or two, so perhaps this is a way forward?

4. Require your own message – MPs complain that too many emails are identikit, but while many of us try to persuade supporters to personalise the messages they send, have we tested what the drop off would be if we required supporters to come up with their own subject lines, or add in a reason why your signing? It wouldn’t solve the volume question, but could mean that MPs couldn’t accuse of us of just sending ‘identikit’ messages.

5. Better integration with casework software – many MPs who have large amounts of casework use software to track the requests that are coming in from constituents. How many of us are looking to see how we can incorporate our actions and messages into these?

6. Email to letter – Given I have an app on my phone that can turn my photos into a personalised postcard that can be sent in the post to a friend, could the same technology be developed to turn my email to an MP into a letter. It’d place a cost on the organisation behind the campaign, but it’d present the opportunity for delivery via another channel.

7. Snapchat – I can’t pretend to understand Snapchat – which probably means most MPs won’t either) but opportunities do new communication channels like Snapchat or WhatsApp provide new ways to communicate with MPs?

8. Bots – Florian from MoreOnion wonders here if the rise in the use of AI means that we’ll be able to design bots that will be able to automatically capture and engage in a campaign action – could that help MPs respond to our requests.

I’m sure other solutions exist , as well as examples of where petitions are having an impact – in the same presentations that I took that image from Stella Creasy talked about the importance of ensuring a petition is part of wider advocacy strategy – she specifically mentioned Friends of the Earth Bee campaign.

Either way what strikes me from the list above is that organisations have to be prepared to adapt and change rather than just defaulting to ’email your MP’. I look forward to hearing thoughts from others of how we make this tool work to have the maximum impact.

Leadership in campaigning – some thoughts

The further I’ve gone in my career the more I’ve been thinking about what leadership in campaigning looks like and the more I’ve found that there aren’t easy answers out there.

So it was great to be asked by Jim Coe to chat with him about some of my thoughts about leadership and campaigning a few months ago. You can listen to the whole podcast here, but preparing to speak with Jim and thinking about the topic has got me thinking.

There is of course a legal and project management element to campaign leadership – it’s important to know about the latest regulations from the Charity Commission, or how to manage a budget, or ensure good external stakeholder relations. But what I don’t find is writing about how to lead teams of campaigners or campaigns.

On leadership, I’ve been really inspired and informed by the writing of Margaret Wheatley, who wrote this excellent and very accessible paper (it’s only 6 pages long) on ‘host leadership’ a few years ago.

Most of us aren’t going to the be the ‘heroes’ who are the ‘face’ of a campaign or a cause – indeed I think there is a whole post to write about if the model of campaigns with a ‘figurehead’ leader is largely redundant.

But for those of us in leadership roles in campaigning it’s a really important paper to read, because it speaks to the challenge of managing and leading talented individuals who are hungry to change the world, working in complex (and often changing) situations where plans evolve and the external environment can shift at a moments notice.

So I’m really putting some thoughts out here, not to present them as a ‘blueprint’ but to spark a conversation amongst others in leadership roles in campaigning.

As a campaign leader I’ve found the following important;

1 – Help those around you make sense of the story – Helping others to step back from the now and understand how does a specific win or campaign fit into the bigger picture of the change that you’re going to achieve, how does that win further the cause that you’re all working for.

2 – Intentionally invest in others – This isn’t unique to leading campaigners, but there can be so much ‘doing’ in campaigning that it’s hard to find the time to pause and make sure people are investing in their personal development. What that looks like will be different for different people – some will appreciate being encouraged to find a mentor, others will need a recommendation of a good book to read, but holding the space for others to flourish by investing time in them means we continue to cultivate generations of campaigners.

3 – Model what you’d expect from others – Let’s be honest, burnout is a huge problem for campaigners. One of the hardest things that I find about leading a team is trying to model what the right balance looks like – I’m a workaholic. I know I don’t expect others to be ‘always on’ but often in campaigning its hard to switch off. It’s easy to tell others to do it, but as I’ve stepped into leadership I’ve become more and more aware that unless you ‘walk the walk’ you can’t expect to ‘talk the talk’.

4 – Understand my privilege – I was fortunate to spend a day thinking about power and privilege early in my career – it was insightful in helping me to think about this and challenge my approaches. I’ve still a lot to learn, but those of us in leadership need to be aware of our privilege. This from NEON is a really helpful resource to start to think about this.

5 – Recognise weaknesses – None of us are good at everything – so as much as we might not like to admit it – we need to be vulnerable to others including those we lead about what we’re not good at. I’ve found that people respect you for it.

6 – Assemble a team around you – Some of those I most admire in campaigning are individuals like Ralph Abernathy and Bayard Rustin they’re not household names, but they’re those who stood around Martin Luther King as he ‘led’ the civil rights movement. The one question I often encourage people to ask when they’re applying for another job is to ask their potential future line manager ‘who do they go to when they don’t have the answer’. Why? Because the best leaders I’ve ever worked with have had people around them to council and challenge them – leaders who think they know it all invariably fail.

7 – Create the space to be curious and ask ‘why’ – Like taking time out or investing in development, the space for evaluation is often lost in our busyness. Evaluation is more than just completing the indicators form at the end of a project. Campaign leaders need to be hosting those around them to ask some of the questions that Duncan Green was encouraging us to think about – to be curious about why change is happening or share rumours.

8 – Pass it on – I’ve written before about the importance of mentoring and coaching – which means those of us in leadership need to be generous in offering to do just that to those who are a step or two back in their campaign leadership journey. Not sure where to start Campaign Bootcamp has a mentoring scheme that’s always looking for people.

I’ve very much written this to start to kick off a conversation about leadership in campaigning, so please do comment below on what else I’ve missed.

Making change happen – reflections for campaigners

One of the joys of my job is I get to go off to talks to listen to interesting people. Last week I got to enjoy thought provoking hour with Duncan Green.

Duncan is Strategic Adviser at Oxfam GB – basically from what I can tell he employed to write + say interesting and proactive things to help make NGOs and others involved in international development better. If you’ve not come across his writing before I’d strongly recommend his website ‘From Poverty to Power’.

Duncan is about to release a new book ‘How Change Happens‘ and I’d recommend going along to one of the many lectures and talks he’s giving over the next few months – it’s full of lots of useful content.

This session was especially useful as it was focused on those those involved in running and leading global campaigns, as it was part of a fascinating workshop hosted by Save the Children International and World Vision International sharing what they’d learnt from campaigning on the MDGs (and on that topic this learning from Water Aid about there work on pushing on the post-2015 agenda is also excellent).

The session was also packed full of useful insight, and big credit to both organisations to actively looking to share what they’ve found has worked and not worked from the campaigning they’ve been involved in over the last 5+ years.

But here are a few things from Duncan that got me thinking about our approach to understanding change.

How change happens? It’s complicated.

Campaigning isn’t like making a cake – we can’t just repeatedly add the same ingredients, mix them together, put in the oven, and get the same cake time and time again. Instead change is complex, ‘non-linear’, messy and involves multiple actors. Frankly its complicated!

To reflect this campaigners need to grapple with what changes a system, to reflect on the role of critical junctures in driving change (see some of my thoughts on preparing for crisis’s here) and recognise that causality is uncertain. I was struck that some of the models in Pathways of Change are really helpful here.

But our traditional planning approaches don’t accommodate complexity.

It’s not often Mike Tyson gets quoted in a campaigning presentation but his quote ‘Everyone has a plan ’till they get punched in the mouth’ is a 21st century take on the ‘No strategy survives first contact with the enemy’ quote. We need to accept that our strategies aren’t up to incorporating the complexity of the challenges we work on.

Instead Duncan suggests that when we to have two types of theories of change – Theories of Change which look at how we think the system is going to be changing even without our interventions, and a Theory of Action which focus on what we hope the impact will be of the interventions that we plan to make. (see more here)

So we need to start to think differently.

As change makers we need to start to think/feel/work in a different way. We need to nurture an inherent curiosity about how change happens, to listen to gossip which can often help us make sense of what’s happening, to learn to embrace uncertainty, and be reflective to recognise our own prejudices and power. In short, we need to ‘learn to dance with the system’ (this draws on the work of Donella Meadows who’s paper on this I’d recommend reading)

Open ourselves to unusual suspects and voices.

To dance with the system we need to look out for those who are already dancing in the system – that might be more ‘junior’ staff in our offices who are actually more ‘in touch’ with with new trends or approaches, to actively get ourselves out of the ‘thought bubbles’ that are so easily to inhabit, or through different ways of seeing he world, for example Duncan ask why do we draw so much from the scientific/econometric approaches in how we try to evaluate advocacy – could we learn as much from history, sociology or social anthropology?

Duncan’s book is published at the end of the month and available at all good bookshops – I’ve pre-ordered my copy.

How to build strong + people powered movements for social change

Thanks to Facebook Memories I’ve rediscovered these ten positive, proactive steps to build a strong, human movements which I first shared a few years ago.

They were written by David Cohen, co-founder of The Advocacy Institute (who died late last year). I find them challenging, inspiring and deeply practical. I’d encourage anyone involved in movement building to journey with them and trying to reflect on them.

They’re wise words for anyone in the business of trying to achieve social change.

1. Remember where you come from, that you are part of something larger. Celebrate your origins and roots.

2. Listen to the insights and experience of people who are affected by the issues and participate in the efforts. They are the real experts – amplify their voices. Keep professional experts “on tap, not on top.”

3. Keep balance in your work and personal life. Work hard, yes. Meet responsibilities, yes. Make an extra effort, yes. But also add humor and rest. Avoid pessimism and martyrdom.

4. Recognise human frailty and accept it. Set the example by not holding yourself – or others – to rigid or impossible standards that drain the organisation’s energy.

5. Motivate others by sharing responsibility, paying attention to others, and encouraging those who make the extra effort. Give praise when it is merited.

6. Model behavior, or set a good example, by fostering cooperation, sharing information with others, and encouraging others’ leadership. Don’t dominate. Leave space for others to share their knowledge and skills.

7. Insist on a calm approach to solving problems. Set real deadlines. Avoid a crisis mentality.

8. Share credit generously within the organisation, sector, and among allies.

9. Be equally civil to those who share your views or tactics, and those who do not. Agree to disagree and do so without personalising disagreements.

10. Recognise that there are incremental steps in the advocacy journey. Celebrate how far a group has come and what it means to the lives of people. New experiences – like meeting with a bureaucrat, politician, or editor – are as much a success as winning a favourable policy. They build confidence and empowerment that, in many ways, are the most profound and lasting changes. Saver them.

Interestingly these positive statements were based on a list written by a 1980s environmental organiser, Byron Kennard entitled ‘Ten Ways to Kill a Citizen Movement‘ – its also worth a read!

Do we need a new map? How the referendum changed the political landscape for campaigners.

For those concerned that this is becoming a blog about political theory. Fear not. Normal service will soon resume.

But a skill for any campaigner is considering how the changing external context is affecting the issue that they’re campaigning on. As a result over the last few months I’ve been thinking a lot about what the uncertain and turbulent times mean for the political context we find ourselves in.

For a long time we’ve considered politics to be about right and left, and tried to place our targets and audiences on that. We’ve always know it was a little simplistic – David Bull explores this some more – but it works when thinking about who to target and who we need to demonstrates supports our issue or cause.

When you have a right of center government you have to consider who are the allies that you might be able to build on the right that you can engage in your coalition, or think about how you frame your message to appeal to ‘right of center’ voters. And the same happens when you have a left of center government.

But so much feels like it’s changed over the last 12 months I’ve started to think about different approach when considering where we place our targets – especially if the negotiations around Brexit dominate the political debate in the UK over the coming years

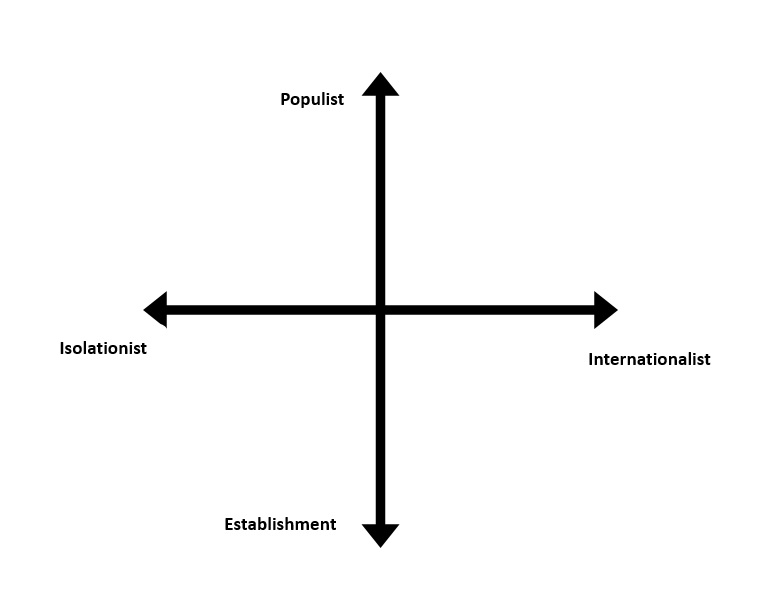

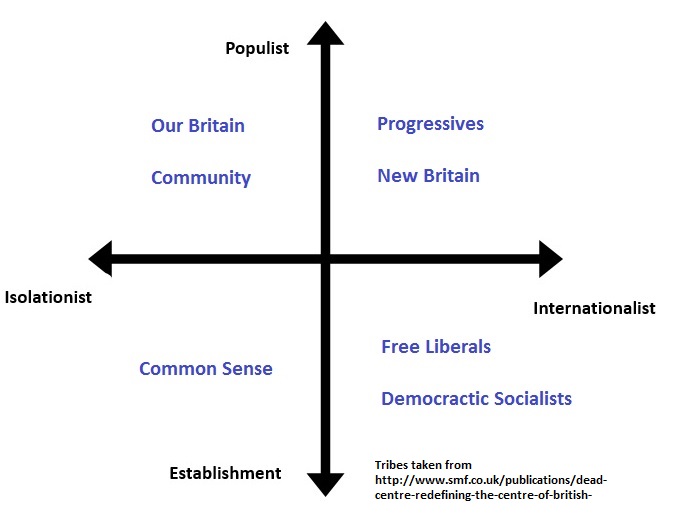

Instead of thinking about Left – Right, I’ve been thinking about needing to work from a Populist – Establishment/Internationalist – Isolationist matrix.

It’s built on the premise that perhaps there are groupings across political parties that have as much in common as others within their parties – we’ve long known that there are factions within parities – but the referendum seems to highlight new alliances across parties – see the emergence of More United led by Paddy Ashdown, or the continuation of Britain Stronger In becoming Open Britain with strong cross party support.

Populist or Establishment – Lots has been written about the rise of Sanders and Corbyn on the political left, or populist movements on the right across Europe and beyond – all of whom have been able to position themselves as ‘anti establishment’. While part of the reason the Remain campaign failed in the EU referendum was that it wasn’t able to shed an establishment image against the more populist message that was being pushed by Vote Leave. This axis also throws up some interesting challenges for me about how many campaigning organisations and our messages are perceived – are we seen as too much part of the ‘establishment’?

Internationalist or Isolationist – this is a question about the range of policies that people want to see enacted, especially when it comes to Brexit. Internationalists are those that believe that the big challenges we face can only be solved by cooperation and collaboration across boundaries. Isolationists on the other hand believe that first and foremost it’s about solving the problems at home – it’s about ‘taking back control’ or ‘pulling up the drawbridge’ depending on your viewpoint.

But if that’s about political targets. What about the public?

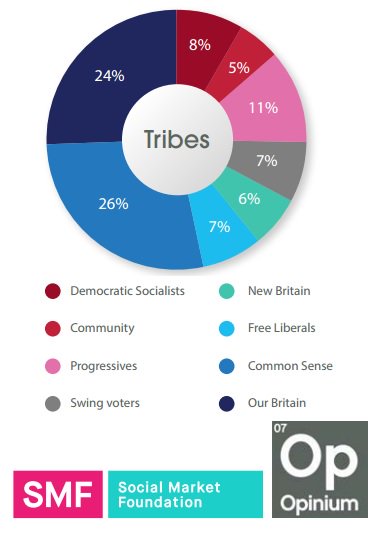

This recent research from Social Market Foundation is well worth diving into. It suggests the public could now be grouped into eight political tribes – these aren’t going to replace the existing parties, but highlights that the political views of the public are more complex, and might shape the possible policy directions of the existing parties, as any good politician is going to think about how they can build an electoral coalition that can win.

I’ve tried to place the tribes onto the Populist – Establishment/Internationalist – Isolationist matrix – which is interesting to consider – especially when you reflect on the relative sizes of the different tribes.

The Social Market Foundation suggest that Our Britain accounts for 24% of the population, compared to 5% for the Community tribe. I think it shows that there is possibly a clear pull towards the Populist/Isolationist side of the matrix which could presents challenges that campaigners are going to have to overcome if politicians feel the need to tack towards that group to sure up electoral support.

I’m not suggesting that campaigners should adopt policies that will appeal to the Our Britain tribe, but as I’ve long argued, as campaigners we need to spend more time considering different perspectives, and understand that we often live in a bit of a ‘bubble’ so we need to become more aware of different tribes. This means finding ways our messages could resonate with other tribes, or find ways of expanding the tribes that support our calls, or at least giving the impression of more size.

Right, that’s the political theory lesson over – normal service will resume next week, but I’m interested in what people think – as a passionate internationalist I’m concerned about the need for voices in the populist and internationalist box that can energize and engage.

10 reflections from NCVO Campaigning Conference

It was the NCVO Campaigning Conference yesterday – it’s always an interesting day bringing together a mix of campaigners and public affairs colleagues from across a range of issues.

As always you walk away with a notebook – or in my case multiple scraps of paper – full of notes, thoughts, good ideas and top tips – and a frustration you couldn’t be in more than one session.

Here are 10 things that I took from my morning at the Conference – do check out #ncvocc for more insight.

1. Brexit is the focus for government – both Jess Phillip MP and Jonny Mercer spoke about how the Brexit negotiations will dominate everything that happens in Parliament and Whitehall in the coming years. It’s not just because it’s the most important political decisions that many of us will see in our lifetimes, but it’s also because it’s taking up so much capacity from civil servant and ministers other issues are getting pushed to the side. Campaigners looking to get noticed will have to push harder than ever.

2. MPs really are tired of email petitions – so this isn’t news, and you almost expect to hear it from MPs in sessions like this, but when two pro-campaigning MPs who are instinctively on our side tell you that they’re fed up of pre-written email petitions, you know it’s time to think long and hard about if the tactic is doing more to hinder than help. Jess reminded us that she get’s over 6,000 emails every day, and the response to any pre-written email is to ensure a member of staff responds with a standard template email.

3. It’s MPs staff you should be getting to know – they’re the gatekeepers to most MPs, the ones who make key decisions about diaries and briefings. Build good relationships with them and it can really help you to get your campaign in front of an MP. Treat them badly and don’t expect to see much progress.

4. Ask do you really need to be in a coalition – I was fortunate to chair a really lively and interesting session on coalition campaigning. Jane Cox from Principle Consulting reminded us that there is a cost to coalitions (perhaps Jane had ready my blog on this) – sometimes a strategic partnership is a better approach than the time commitment an effective coalition can be. Jane wrote a really useful post with some of her learning from coalition campaigning.

5. Keep going until the end – too many coalitions just focus on the immediate change outcome, and when they’ve succeeded in delivering that they stop. That can be a mistake and often ensuring that you monitoring implementation is as important. This is something that you should factor into your planning – especially when applying for foundation support for your campaign.

6. We need to talk about power – Heather Kennedy from the Fair Funeral Campaign reminded us of the principle from organising that you either have organised money or organised power – if you’re opposition is organised money it can be easy for them to ‘sit it out’ until you’re coalition has come to an end. It was one of the few references through the day to power – which given campaigning is often about winning feels like it was something missing from the conversation.

7. Celebrate success in a generous way – Heather shared about how the Funeral Poverty Alliance has built it’s coalition over the last few years and managed to put the issue on the agenda – it sounds like a really great campaign coalition which doesn’t have lots of governing documents but has placed building relationships through well facilitated strategy sessions and strong face-to-face relationships. Demonstrating that coalitions don’t have to be dominated by ‘egos and logos’!

8. When developing campaign leaders high commitment should mean high support – I really enjoyed the session on developing volunteers as campaign leaders – it felt that there was a recognition that in response to the declining effectiveness to e-petitions we need to look again at building our networks.

I’ve been aware of the work that Alice Fuller and her team at the MND Association have been doing at building a network of Campaign Contacts in their local groups over the last few years, but it was great to hear more about it – and to hear some honest reflections about how much the team have learnt about the level of support they need to provide, the commitment to training and investing in volunteers, but also letting go and trusting volunteers.

9. Metrics matter – Eleanor Bullimore spoke about the work, and the challenge of developing relevant metrics to measure the impact of the work that volunteer network at The Ramblers is having. Elle suggested that as well as developing metrics for going up the the ‘ladder of engagement’ we also need to be looking at those going down – recognising that some volunteers will find they have less rather than more to offer.

10.Trust us – Joining Alice and Eleanor was Katy Styles, one of MND Associations local campaigners. It was so refreshing to hear of the ways that Katy had been able to get involved in leading MND’s campaign (Katy has helped to produce this cracking toolkit) – and to be reminded that most people aren’t paid to campaign they do it because of a passion. The big message that I’m taking from Katy was as professional campaigners we need to let go of our concerns about brand and reputation and trust our volunteers.

Update – all the presentations from the sessions are available here.

Book Review – Blueprint for Revolution

One of the things I most enjoy about going on holiday is the opportunity to dip into a good book or two.

Over the last week I’ve really been enjoying Blueprint for Revolution – How to Use Rice Pudding, Lego Men and Other Non-Violent Techniques to Galvanise Communities, Overthrow Dictators or Simply Change the World by Srdja Popvic.

Popvic is one of the leaders of the CANVAS (The Centre of Nonviolent Actions and Strategies), the Serbian based organisation that was behind the movement overthrowing Slobodan Milošević, and has taken these lessons to help other movements around the world (this is a good read on the work of CANVAS).

It’d be easy to think that the book is only intended for those who are interested in learning about overthrowing dictators, but it’s not. I found the book packed full of practical insight and brilliant stories that are relevant to anyone involved in campaigning.

It’s an easy and enjoyable read, with Popvic mixing a range of stories from his personal experience with lessons from history.

I’ll be recommending it to anyone who asks me about what makes a good campaign as it’s packed full of practical wisdom that could be applied to anyone involved in movement building.

Here are a few lessons I’m walking away with after reading the book that I’ll be looking to apply in my campaigning;

1 – Focus on small victories to build your movement – those campaigns that focus first on small achievable battles that they can win are more likely to succeed. They understand that victories can help to give your supporters confidence that they’re part on a winning side, and also help to attract others to your cause.

2 – It takes time to plan your strategy – Popvic shares a lot about the time Otpor! in Serbia took to plan and build for the actions that they then took. He’s at time critical of movements that he feels have moved to action too quickly. To be successful you need to be meticulous as you can in your planning and preparation. Leave nothing to chance.

3 – Change comes when two or more groups come together for mutual benefit – campaigns can’t be won if they just reflect the views or worldview of just one group with a community – they need to bring together different groups. Throughout the book is the message that building unity, community and trust with others is central to anyone who wants to win.

4 – Focus on the ‘Pillars of Support’ – remembering the work of Gene Sharp, who suggested that every regime is held in place by a handful of pillars – apply enough pressure to one or more pillar, and the whole system will soon collapse. But this means thinking laterally and considering what the pillars are – for example for using businesses which have close connections with those you’re looking to target. See this for how the concept has applied to the campaign for equal marriage.

5 – Make it funny – campaign can be a serious business, but Popvic is a big advocate of using ‘laughtivism’ as a tool for change, using humor as a way of undermining your target, but having some fun at the same time.

The book is, as they say, available from all good bookshops – I’d highly recommend it.

How Theory of Change can help your campaign win gold

Suggesting campaigners spend some time thinking about Theory of Change doesn’t normally elicit the same energising response that cheering on Team GB in the Olympics does!

So while I’ve been spending the last two weeks watching the Olympics, it’s got me thinking about winning and the approach that UK Sport has taken to ensure this was our greatest ever Olympics.

It strikes me that they have an incredibly clear theory of change about how they we’re going to approach Rio 2016 and build on the success from London 2012.

But what could campaigners learn from the rush of medals Team GB has won in the last fortnight?

Alongside other colleagues at Bond, we’ve been working with Jenny Ross to produce resources on Theory of Change which we hope will help to provide a useful introduction, and encourage more campaigners to use it as an approach.

Theory of Change is a key approach for any campaigner who is serious about winning to take, but one I think many of us shy away from as it’s been built up into that’s impenetrably complicated, so we hope that this video and accompany resource will help to make it more accessible.

So drawing on the lessons from the success of Team GB here are a few thoughts on how theory of change can help you approach planning your campaigning;

1. Be clear on what success looks – It’s simplistic to suggest that all Olympic athletes are going for Gold. Yes that’s what they want to achieve, but many realise it’s unlikely, but for sports that UK Sport funds it’s clear on how many medals they’re looking to achieve.

Using Theory of Change can help you be clear on what your specifically looking to achieve and be able to articulate it for all those your working with.

2. Map out the route to success – Listen to any of the Olympians and they’ve been successful by building up to the competition in Rio. It has come about through months and years of planning and meeting milestones on the way – achieving certain targets in training, winning an important competition, etc.

In the same way using Theory of Change can help you to set out what the progress on the way that you expect to see before winning the overall change – it helps you to map out the goals that you need me to meet on the way.

3. Challenge your assumptions – One of the issues where UK Sport has been criticised is the way it ruthlessly allocates resources to sports where it believes it has a medal opportunity, even when they’re unpopular. It’s a harsh approach but one which clearly produces results by making sure resources are going to the right place.

In Theory of Change, we’re asked to test our assumptions and to make sure that the resources we have are being allocated in the most effective way to deliver the outcome – just because we’ve always done something doesn’t mean we should continue to do it.

4. Look for marginal gains – Those being Team GB success in the velodrome are famous for a focus on marginal gains, which is all about small incremental improvements in any process adding up to a significant improvement when they are all added together. It means when it comes to winning nothing is left un-investigated.

Theory of Change asks us to think about the context within which we’re working, and what that will mean for the work. To investigate and consider all the factors that might help or hinder us on our route to winning.

5. Reflect, review and repeat – Listen to the interviews with officials in UK Sport and they’re already planning for Tokyo 2020, building on the success and learning of the last 16 days.

It should be the same with Theory of Change, it isn’t just a document to be produced and forgotten. It should be a living document that responds and reacts to – looking forward to the next opportunity.