For the last few months, I’ve had a growing pile of books by my desk, all of which have sparked a half-written blog post in my head, but as the year comes to an end I’ve decided that’s unlikely to happen, and so to put them into one blog with some of the key learnings I’m taking away from them.

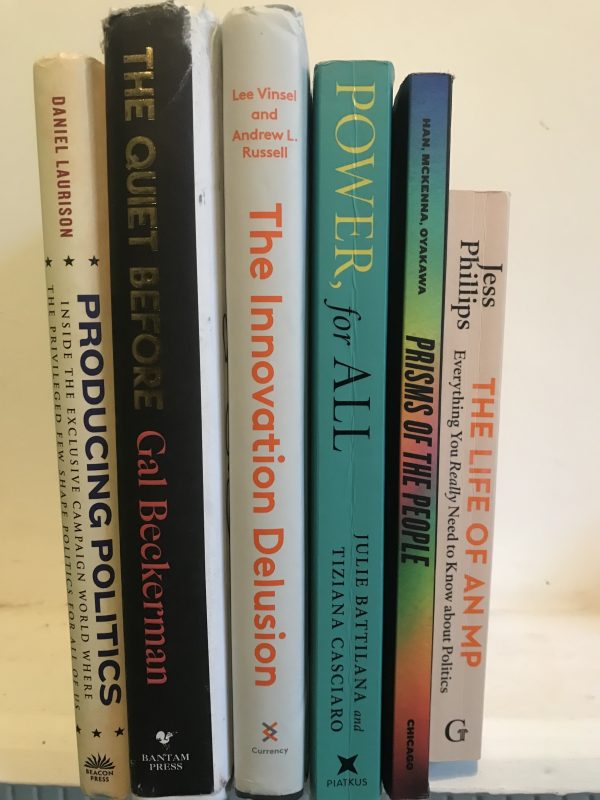

Prisms of the People, authored by Hahrie Han, Elizabeth McKenna, and Michelle Oyakawa, is a cracking read which came out at the end of 2021. Much of what I find helpful is how it’s been super helpful in sharpening my thinking and approach to how we understand power. Linked to the book being published was this really useful paper and these 4 principles which I’ve been trying to reflect on during the year;

- Power is dynamic – too often we think about power as static, that an organisation or movement has it or doesn’t have it, but it’s so much more complex than that. It’s about the interactional relationship between (at least) two political actors.

- Resources do not equal power – sure it can help, but just because you have a big mailing list doesn’t mean you have power. Simply amassing one resource will not automatically lead to power. Movement building is the work of the process

- There is a difference between potential power – the resources organisations need to be ready to exert power in the world when the opportunity comes, and the exercise of power – the actual things your organisation does to exert its power in the world (win elections, pass policies, turnout activists).

- Power is like an iceberg – after Steven Lukes it has at least 3 faces (visible, hidden, and invisable). You can only see the tip of the iceberg (the visible power) but much of it remains submerged underwater (‘hidden’ power). Too often as activists, we just think about the visible power, but ignore the other faces of power.

Reflecting more on power, I also enjoyed Power for All by Julie Battilana and Tiziana Casciaro, it’s a wide-ranging, but very accessible read that acts as a primer to how power can be harnessed to make positive changes in our lives, work, and societies – I found the chapter on power in movements really interesting, and especially the research by Julie on how every successful social movement requires three distinct leadership roles: the agitator, the innovator, and the orchestrator.

As the authors write in this paper, a movement needs those threes roles to work together with the;

- Agitator stirring the pot by articulating and publicising grievances, rallying an otherwise diverse group of people around a mutual desire for change

- the Innovator developing solution to address the grievances – and helping to justify those alternatives in appealing ways to engage individuals, groups, and organizations to support them

- finally the Orchestrator spreads the solution created by the innovator, thinking how best to reach and work with people both within and outside the movement.

The chapter also picks up on the need that most changes come about through the long and hard work of movement building, something that isn’t necessarily glamorous or that gets much attention but is required for sustained action.

On that theme, Gal Beckerman’s book, The Quiet Before, is a really interesting and thorough look at the important work of how ideas and movements are incubated and grow often initially unnoticed.

Drawing on a range of examples from across the world and history Beckerman draws out on the importance of that quiet and unnoticed work that happens in the incubation stage of a movement before, reflecting on the challenge that our social media-driven culture means that we often move immediately to the ‘trigger’ without the work of building a shared movement identity which means it can be hard to sustain beyond an initial moment of outrage.

Tracing movements like Chartists in the 1800s to the democracy movement in Russia to Black Lives Matter, Beckerman looks at how the pre-digital forms that often required individuals to spend time writing down and honing messages, discussing and debating ideas, refining ideas and arguments, and building a sense of shared identity.

And while we can’t go back to that– as we end the year with the future of Twitter looking uncertain, there is a truth in examples from the book on in the importance of that slower work of building our networks for change, and appropriate response to this challenge from Bill Mckibben that ‘we’ve almost certainly relied too much on Twitter ….posting has become a substitute for other kinds of action…it’s given us less incentive to build out real and substantial networks’.

It was David Karf’s post on rethinking political innovation, that pointed me in the direction of The Innovation Delusion by Lee Vinsel and Andrew Russell – not everything in the book was relevant, but its central message that we’ve become obsessed with labeling everything as innovation and always looking for new when actually we should also be focusing more of our work and efforts on maintenance.

I know how much I can be drawn to celebrating or searching for the ‘new’ when it’s as important to focus on maintaining what is already there. The book offers a useful set of principles for a maintenance mindset – that it can sustain success as when done well it can ensure longevity and sustainability, that doing so depends on culture and management – a good challenge that we need to celebrate those heroes who as much as we praise those who we see as innovators, and maintenance requires constant care (and time put aside for that).

Books that give an insight into what really happens inside the institutions, and Jess Philips, The Life of an MP, is funny, and a contemporary example of just that. It’s a truthful, and engaging look at how MPs have to juggle their constituency and casework, with a push for progress on other interests they have or causes they support.

Of course, the way every MP works is different, but Philips does an excellent job at presenting honestly the reality of that balance and providing some useful tips and advice to any campaigner. Lots of books about contemporary politics can be interesting reads, but they are about what’s happened and how what, this is a little different as it’s much more about what’s happening on a daily basis for an MP.

My final book is Producing Politics by Daniel Laurison, it’s a sociological look at what happens inside US political campaigns and the reality that most decisions are made by a small group of individuals who move from one campaign to another. Given the site of study is the US political system which is very different from the UK, not all of it is relevant (although it’s an interesting read if like me you are a bit obsessed with US politics) but a few reflections from the book stood out for me and I think do translate more widely.

The observation that much of what happens within campaigns isn’t driven by data and evidence but by ‘follow handed down by one campaign to the next’, that campaigns should be sites where there is lots of engagement with the public but too much time is spent with others who share – a challenge to get out more, and that too little time is spent building deep and meaningful engagement despite the evidence that it can have the most transformative impact on the outcomes all resonated with me.