Some dismiss craftivism as not ‘real’ campaigning. If that’s you, I’d challenge you to read ‘How to be a Craftivist‘ by Sarah Corbett, and see if you still hold the same view after reading it.

I’ve just finished Sarah’s book, which was crowd-funded by hundreds of individuals (including me and my wife), and explores what the art of gentle protest is.

I struggle to think of a single book that looks at an approach to campaigning with such rigor and reflection. I can’t recommend it highly enough, even if you’re someone who doesn’t feels comfortable with a needle and thread in your hand.

The book is in part a how-to handbook and in another part a call to a better form of campaigning. It’s brilliantly written, and a really wonderful, uplifting, inspiring and encouraging read. If only every branch of campaigning had someone who took the time to think deeply about their campaigning craft and share it with the rest of us.

As I’ve written before that I think that we dismiss craftivism not as ‘real campaigning’ at our peril, and that’s a view I’m even more sure about after reading ‘How to be a Craftivist’.

Having finished Sarah’s manifesto, I’ve also been reflecting if all campaigners could benefit from the following 5 traits of gentle protest, whatever your preferred form of activism;

Thoughtful – Craftivism isn’t simply about making something that looks ‘nice’ – although that’s helpful. As Sarah explores in the book it’s about really thinking about what will resonate most with the target that you’re looking to influence. I love the campaign that Sarah ran with Share Action to get Marks and Spencers to pay the Living Wage.

Each activist was given a member of the board to stitch fora and was encouraged to research the board member, and stitch a hankie that contains words, images, and ideas that would resonate with them. When they were delivered many of those they handed to them engaged in meaningful conversations. That thoughtfulness in connecting into what will engage with our ‘targets’ really resonated with me. How do we help those we’re looking to influence understand the commitment we have to our issue.

Slow – So much of our campaigning is about responding quickly but in the busyness of getting our latest email action out or responding with a clever tweet. Now the book isn’t suggesting that we should stop doing ‘fast activism’ for ‘slow activism’, but instead presents a challenge. That when so many of the issues that we’re working on are big, complex and complicated, we sometimes we need to slow down to go further. To find approaches that let us reflect on where we’ve come from, and where we’d like to go.

Communal – Craft might sound like a solo activity, but around the world, the Craftivist approach has been bringing groups together. Many who join would never consider getting involved in a campaigning activity, especially a march or a protest, it’s bringing people together, getting them to find community over the act of stitching and building connections to sustain activism. But beyond that, I found the story of organising her first protest outside Primark, which saw Sarah reflect if the protest had done more to build a divide rather than a bridge, and the challenge to organise protests that open people up to engage with our message a really inspiring one.

Graceful – As a campaigner, I’ve never been asked by my MP to stop sending them issues, but Sarah has. She writes in the book about her experience of lobbying her Conservative MP. She was sending their office so many emails they asked her to stop. Instead, she took to stitching a message on a hankie to them and asking for the opportunity to meet. That helped to open up a dialogue and conversation.

I don’t get the impression for the story that Sarah has started to vote for this MP, but in a world where it’s easy to see our opponents as our enemies, it a reminder of a more graceful and generous approach to our activism. Where we see those we’re seeking to persuade as those we have more in common with.

Mindful – I was struck throughout Sarah’s book that the approach to craftivism is a real sense of intentionality in the way in which you approaching design – from the color of material you choose to use to the messages you share. It’s a mindful intentionality that we could all learn from. But beyond the approach to design, it the constant message in Sarah’s book that you need to approach your campaigning with a mindfulness that reflects the decisions and choices you make about your campaigning.

Author: mrtombaker

Could Vicars help us overcome the 'Activist Paradox'?

US megachurch pastors might not at first glance have a huge amount in common with campaign activists, but both have interesting thoughts on how you go about building a movement.

Jamie Bartlett succinctly describes the ‘activist paradox’ that many movements face in his book The Radicals describing “the way a self-selecting groups of similar people create a powerful shared subculture — ideas, language, received wisdoms, behaviours — that help them bond and commit to the cause, but in so doing create a subculture that makes non-members feel like it’s not really for them”.

As someone with a foot in both the campaigning and church community, I’ve a long interested in the lessons that activists can adopt from the church to help them overcome the ‘activist paradox’ that many of us experience in the work that we’re doing.

As I was reading Jonathan Smuckers ‘Hegemony How To – A Road Map for Radicals’ earlier in the year, I found myself reflecting back on some of the principles of church growth.

A really good summary of those principles can be found in Rick Warren’s Purpose Driven Church. It was a book that was extremely popular within the church growth movement around 20 years ago, and lead to this brilliant paper ‘Purpose Driven Campaigning’ written by Australian agency, on which I’ve drawn some of the lessons in this blog.

Here are 6 things that perhaps activists could learn from the church pastors about growing a movement;

1- Be sensitive to those attending for the first time – churches should be willing to adapt what they do when the unconverted are present – they need to be constantly asking if the shared rituals that they’ve developed make sense to those who are attending for the first time. Warren also highlight the need to create an atmosphere of acceptance, that you need to be nice to people when they show up. Obvious advice, but something easy to overlook!

2 – I see your pyramid of engagement and raise you the circles of commitment – As campaigners, we spend lots of time thinking about how we can move people up the pyramid of engagement. For church leaders, the goal of a church should be to move people from the outer circle (community – low commitment) to the inner circle (core – high commitment). For the community, Warren encourages churches to focus on bridge events that bring them in – think social, think non-threatening, then look to get people in small groups to build connections with others, while for the committed you should look to offer training and for the core to focus on leadership development. See a brilliant article on the principle behind the ‘circles of commitment’ here.

2 – I see your pyramid of engagement and raise you the circles of commitment – As campaigners, we spend lots of time thinking about how we can move people up the pyramid of engagement. For church leaders, the goal of a church should be to move people from the outer circle (community – low commitment) to the inner circle (core – high commitment). For the community, Warren encourages churches to focus on bridge events that bring them in – think social, think non-threatening, then look to get people in small groups to build connections with others, while for the committed you should look to offer training and for the core to focus on leadership development. See a brilliant article on the principle behind the ‘circles of commitment’ here.

3- Avoid the ‘problem of the core’ -too often in churches a small group who start off something together that they develop a core mentality. Forgetting the original reason that brought them together they such close-knit fellowships which make it impossible for newcomers to break in. Warren encourages churches to take an ‘inside-out’ approach – by focusing on growing from the outside in, by actively designing programmes for each group in the circle of commitment. This is a trap that I see many activist groups fall into, so being aware of the ‘problem of the core’ is key to avoiding growth stalling.

4 – Ensure you a purpose-driven – Warren suggests that churches should restate their purpose on a monthly basis to keep an organisation moving in the right direction, and encourages churches to ensure the purpose of the church is communicated through symbols, slogans, and stories. It’s a good reminder to campaigners that vision needs to be continually highlighted in our communications.

5 – Seek a commitment from people – churches should focus on turning people into active members. The manner in which people join an organisation will determine their effectiveness for years to come. Make them feel special by selling them the vision for what they’ll achieve rather than the cost of getting involved – this to me has parallels with the idea of ‘asking big’ in the Bernie Sanders campaign.

6 – Know who you are fishing for – Warren says ‘people don’t voluntarily jump into your boat so you need to go and catch them’. To do that you need to reach people on their terms, which means thinking about your messaging, offering multiple ways and making it as easy as possible for people to get involved. Again sage advice for those finding ways to help activists increase in number.

How to sustain the energy in your campaign

I’m off to chat to the good folk in the campaigns team at Battersea Dogs and Cats Home later today about how to keep the energy going in your campaign. It’s been a really fun question to be thinking about – not least because I can use a cute cat picture to illustrate this blog.

But as I’ve been preparing I’ve been struck that we often spend so much time and effort on planning the launch phase of our campaigns but don’t think about how to sustain the energy and momentum that we need to secure change.

As, George Lakey, said in his London lecture earlier this week, “a campaign, in contrast to a protest, is going at it over and over again, and escalating at the point of vulnerability of your target until you succeed”.

So here are 9 thoughts about sustaining the energy in your campaign;

- Think about the moments that people care about not moments you care about – too often we focus our campaigning around pushes that fit our policy calendars. There can be a rationale to that, but why not look at alternative moments that might help to get your campaign noticed in an a different light.

- Mind the moment gap – thinking about moments means that we can get caught forgetting what’s going to happen in the gaps. It’s hard to sustain the same level of output for a long period of time, but planning ahead and thinking about how well placed media work, a opinion poll or another approach.

- Ask what’s working/what’s needed – if you have allies inside your target, why not ask them what’s working or not working. What tactic could help to make the biggest different at that moment. They might make suggestions that you’ve not thought about or how to open up a new flank in your campaign.

- Share, and re-share, great content – shareable content is king, but too often we produce it without thinking about audience insight, or rush to move onto the next great idea without pushing it out enough. In a time when we’re bombarding by so much content, repackaging and reusing content is too often overlooked. The same goes for message discipline, I’m struck by how much time Shelter put into repackaging the same message in their housing campaigns.

- Never let a good crisis go to waste – it can be easy to see crisis as moments that you can’t plan for, but I’m not sure that’s true. Most crisis can be anticipated even if the exact timing can’t be pinned down. They’re great opportunities to reach new audiences or create a renewed push behind your policy ask. I thought Which? did this brilliantly around the RyanAir flight cancellations recently – they presumably know that a crisis was going to occur and had the content ready for it. What’s the equivalent for your campaign issue?

- Explore allies and alliances – bring in new people to your issue by thinking about how you can take it too new audiences. Too many campaigns try to focus on energising the same group of people to get involved over and over again, but those that are able to reach out to new groups can immediately bring in new energy.

- Claim it – Campaigns with big ambitions can sometimes lose energy and momentum, but like your teacher would have advised you when planning your revision timetable, it’s easier to eat a chocolate elephant a little at a time.

Breaking down your campaign and building in winnable milestones can really help. We’re running a campaign on the conflict in Yemen at work at the moment. It’s a big problem to solve but by focusing our campaigning on milestones, like getting the UN to list the Saudi led coalition in a key report, has helped to provide milestone win to keep supporters feeling like the actions they are taking are making a difference. - Give it away – provide campaigners with the tools and content to make their own and get out into their communities – it’s a key approach that many distributed campaigns take, allowing the energy and ideas of those closest to a community to engage in a campaign.

- Abeyance – while many campaigns are right to keep going, sometime a period of abeyance can be the best approach, a period when a campaign isn’t in public view. We perhaps sometimes forget that it took over 100 years for the campaign to end the Slave Trade to be successful.

What other ideas and lessons do you have about how campaigns can sustain the energy needed to win?

GDPR – what is it and why should campaigners care about it?

I’ll confess as a campaigner thinking about data and data regulation, isn’t one of the most exciting parts of my work.

But, the GDPR, or the General Data Protection Regulation to give it its full title, are important EU wide changes that will impact all organisations, including charities and campaigning organisations, who hold data about members of the public. And with the GDPR coming into effect in May 2018, it’s worth spending a few moments engaging understanding what it is and what it could mean.

Important disclaimer – the points below are drawn from reading a number of really helpful guides to the GDPR. I’m not a GDPR/data expert, so please check in with someone who is if you have specific questions.

Here are 7 things that you should know;

1. It covers all communications – lots of recent regulations have focused on fundraising practices, most prominently through the ‘opt-out’ from the Fundraising Regulator, but the GDPR affects anything that involves processing an individual’s personal data, which includes who can receive your campaigning communications or information held by volunteer campaign groups.

2. It’s not a moment to panic – We already have lots of guidance and regulation about how data is processed and held, so many of the GDPR changes are an ‘evolution, not a revolution‘. Plus there is still lots of time to make sure that you’re compliant, and loads of people are providing helpful advice – my big recommended starting point is to look over the IoF report, which, although written for fundraisers has lots of practical advice, as does this NCVO guidance.

3. It is about clear consent – At the heart of the GDPR is being able to show that consent to use someone’s data has been ‘freely given, specific, informed and an unambiguous indication through a statement or clear affirmative action, such as actively ticking a box’. So it means that there has to be a clear ‘opt in’ to getting further communciations. The guidance suggests that pre-ticked boxes aren’t appropriate, and you’ll need to be able to show how the consent has been given if someone asks. You also need to have explicit consent if you plan to share the data with third-party providers.

4. Review the information you currently hold – ahead of the GDPR coming in you need to be reviewing what data you hold. So now is the time to make sure you’ve looked at all those extra spreadsheets and lists you might have with personal data in, and also make sure you’re aware of the changes that the GDPR brings to communicating with under 16s.

5. Power over information – The GDPR gives individuals more power over the information you hold on them, including being able to ask to have their personal data deleted from your database, being able to request what information you hold on someone through a ‘subject access request’ (there is a campaign tactic in this as well I think) or to be rectified if it’s not correct. Again it’s thinking about what that means for the information you hold.

6. Work with others within your organisation – if your organisation has someone who is responsible for your database if you’re not already, it’s time to talk with them about what they’re doing and how you can help. If your data management approach is shared across different teams make sure you’re starting to talk together.

But either way, start to check in with others, and also make sure that you’re drawing your board or senior management. Although they might not do the work of implementing the guidance, the risk of not being compliant means they need to be aware, not least as the fines from the Information Commissioner for data breaches are much higher.

7. Share with others outside your organisation – Some of the most ways that organisation have found to grow and build campaigning lists will have to change under the GDPR, but that shouldn’t mean that growing your list, re-engaging lapsed supporters or supporting local groups isn’t possible. Organisations sharing approaches that are working and compliant will be really useful in ensuring that this is regulation that stifles campaigning.

Still looking for more on the GDPR? Then I’d recommend a read of GDPR: The essentials for fundraising organisations by the IoF and How to prepare for GDPR and data protection reform by NCVO. The official ICO guidance is here.

Inside a failing campaign – lessons from the Conservative 2017 election effort

Regular readers will know that I believe you can learn as much from an unsuccessful campaign and you can from a successful one.

Conservative Home editor, Mark Wallace, publishes a three part insider look at why the Conservative campaign failed at the General Election (part 1, part 2 and part 3). It’s a really great set of articles which gets under the bonnet of what did and didn’t work at an operational level – rather than too many post-elections which focus on the personality clashes between competing politicians. As an aside, I’d also recommend Mark’s writing on the referendum campaigns.

Although the articles are written with the intention of trying to change practice in the Conservative Party going forward, there are a number of lessons that I think can be applied whatever issue your working on. I’d strongly recommend that you read at least the first two articles, but here are the takeaway lessons that I’ve taken from the articles;

1 – You can’t fatten a pig on market day – the famous saying of Conservative election guru, Lynton Crosby, as a reminder that successful campaigns take months, sometimes years of meticulous planning. That it takes time to have the right staffing infrastructure in place, message testing done and materials ready to go. It really is a process you can’t rush.

2 – Get the right people on the bus – successful campaigns need the right people, with the right experience, making decisions at the heart of them. Wallace’s articles include numerous about the lack of clarity in decision making, too many people involved at the tops and the fact that many experienced staff had been let go after the 2015 election. You need to have the right skills and experience to win.

3 – Practice open loop listening – Conservative activists on the ground were repeatedly finding that the data selections that they were being given we’re missing often known Conservative voters, but despite feeding that upwards the data selection stayed the same. Those at the center of the campaigns were so sure that their models were correct the ignored what those on the ground were telling them, a classic example of closed loop learning.

4 – Data deteriorates fast – at the end of the 2015 General Election, the Conservatives had over 1.4 millions usable email addresses, but fast forward just 24 months, and the articles suggest that up to much of this data was out of date (as a reference between the 2010 election, when they had collected 500,000, and 2013 when they started planning for 2015, the list had shrunk to 300,000). A reminder that any campaigning organisation needs to be proactive at continuing to collect data.

5 – Distributed v’s Centralised – the campaign was heavily centralised, with a focus on a few core messages – remember ‘Thresea May’s Conservative Party’ and ‘Strong and Stable Leadership’. This meant there was little space in literature for candidates, who often have a much better sense of what messages would work in a community. That lead to big errors, for example literature featuring quotes from The Sun being sent to seats in and around Merseyside where their is a significant anti Sun feeling, but the same approach surely meant the Conservatives missed opportunities for picking up effective local campaign led by candidates. As a contrast, Ben Pringle has some reflections on how localised campaigns helped the Labour Party

6 – If it ain’t broke don’t change it – Following the 2015 General Election, the Conservatives had found a number of effective approaches working both in individuals constituencies, and how to make the most of working with activists. But many of those approaches were thrown out for 2017. Sure innovation and changing approaches is important, but not at the cost of the basics that have been proven to work.

7 – Message amplification – Wallace reflects on the role that a range of third party organisations and individuals were active at amplifying the messages coming from the Labour Party – the micro-PAC phenomena I’d highlighted in this post – while the same didn’t happen for the Conservatives. A good reminder that the reach of your own social channels, however large, can only get you so far, and you need to build a wider network of support. See more on this over at Political Advertising.

8 – Don’t forget to say thank you – Imagine you’ve just put your life on hold for 8 weeks to run to be a candidate, you’d expect in the days or weeks after election night that you’d get a personal thank you for those who’ve lead the campaign. That didn’t happen for most Conservative candidates, they got a generic email, sent to thousands of other helpers, and that was about it. Not good for motivation!

If you’ve read the articles, what other lessons are you taking from them?

What stops us embracing an organising approach?

A colleague in some recent handover notes wrote ‘while we talk a good game on organizing, we’re still really focused on mobilising’, or something to that effect. It’s a very fair challenge and one that I’ve been reflecting on since reading it.

Like many in the campaigning sector, I’ve got really excited about the opportunities that an organising approach to campaigning brings – not least because I’ve been inspired by the campaigns that are using it and winning, but the day to day model of campaigning that I’m most accustomed to is a mobilising one, and getting from one approach to another isn’t easy.

So I was really excited to get a copy of Matt Price’s new book ‘Engagement Organizing – The Old and New Science of Winning Campaigns‘ at the start of the month. I’d met Matt at the MobLab Campaign Con in Spain last autumn, and read some of his online articles looking at campaigning approaches in Canada.

Matt is based in Vancouver, so the case studies are drawn from NGO, Union and Party Political campaigns that are north of the 49th parallel. We might look across the Atlantic to the US for most of our inspiration, but the reality is that the similarities in political systems in Canada mean we’ve probably got as much to learn for our campaigners, and it was really nice to read some case studies of campaigns and organisations I wasn’t so familiar with.

But what I really like about the book is that it’s a practical how-to guide, that looks to blend together how campaigners can draw on the best of the digital. Instead of trying to push a particular organising perspective, or suggest that everything can be won by smart digital campaigning, the book explores how to blend these approaches together for maximum impact.

Lots in Matt’s book resonates, especially the chapter on the Engagement Cycle, as opposed to the more traditional pyramid of engagement, and also the stories of the approach of Cesar Chavez and the United Farm Workers in using house meetings as an organising approach.

At the end of the book, Price offers some reflections and challenges that prevent NGOs from embracing this approach. They got me thinking back to the challenge from my colleague, and if they’re true in the campaigning that I’m doing;

1. The work is hard – Price writes about the challenge of ‘organizers entropy’ suggesting there isn’t always enough energy in the system to do useful work. That means that organisers need to keep bringing energy into a system, and that often a win can take energy away as those you’ve organised feel that their goal has been achieved. That resonated – moving to an organising approach means keeping moving away from the norm. It’s learning a new memory muscle, and that can be exhausting. As a campaigner, I need to keep bringing energy into the system, and to those pushing this work forward.

2. Resources – while the ‘snowflake model’ shows that you can build an approach at scale with volunteers, and digital tools have lowered the costs for campaigning, Price points out that even then organising at scale costs money. Something that can be especially challenging in organisation where you need to continue to demonstrate impact and value for money. Again this feels very relevant – how do I resource the slow but important work of taking an organising approach, when the mobilising approach can demonstrate ‘quick wins’.

3. We don’t review our ‘stop doing’ lists – rather than a ‘to do’ list, Price suggests we need to ask some hard questions of what we’re already doing, and ask if they’re the most important things we can be doing to ensure we’re effectively using time and resources. It’s a really neat idea, and Price has some helpful questions to ask to help do it;

4. Overcoming organisational inertia – Linked to the work is hard, is the challenges we can face within our organisations with systems, practices, and cultures that are hard to change. Some of that comes from the experiences, practices, and expectations of those who’ve risen to more senior roles who’s campaigning was shaped in a more broadcast era (I count myself in this), some of it is about the systems we use which aren’t built, while culture is often seen as the ‘way we’ve always done things’ and is hard to shift. I’m not sure I have any simple solutions to this, but it’s something I’d like to reflect upon in future posts.

5. We need to talk about power – One of my reflections from time spent with Hahrie Han last year is that an organising approach requires us to have more conversations about power – its something that came through again reading the book. Both about how we give it away, alongside control to those we’re seeking to empower, but also how we ensure we’re directing our campaigns to focus on where the power is. As Han says ‘movements build power not by selling people products they already want but instead by transforming what people think is possible’.

I’d recommend Matt’s book for anyone interested in how to embrace a more organising approach in their campaigning.

A Summer Reading List

Summer is here, so I’m going to take a brief break from blogging during August. I’ll be back in September, but if you’re looking for some great content to keep you thinking over the coming month, here are some recommendations of some ace books, blogs and podcasts to keep you busy.

Books I’ve enjoyed;

1. Hegemony How-to: A Roadmap for Radicals – Jonathan Smucker’s honest look at why movements too often fail, and what we can do to avoid being closed groups. One of those books you find yourself nodding at as you read + highlighting sections of it!

2. The Myth Gap: What Happens When Evidence and Arguments Aren’t Enough – Alex Evans has written a really enjoyable read about the need for us to rediscover the power of stories and myths to inspire change.

3. Analytic Activism – David Karpf looks inside Move On, Avaaz and other online campaign platforms approach. It’s one of the most accessible academic books I’ve read, and full of useful learning. Good podcast with David here if you’ve not got time to read the book.

4. Radical Candor – I took a while to get into this, but have been recommending Kim Scott’s book on how to give and receive feedback as a manager, but found it really helpful for anyone managing a team.

5. The Talent Lab: The secret to finding, creating and sustaining success – a really interesting look into the drivers behind the success of the GB Olympic team. As I suggested in my post on what we can learn from Chris Froome there are lots of lessons for campaigners to reflect upon from winners.

Books I’ve had recommended to me which I’ll be reading in the coming months;

1. This Is An Uprising: How Nonviolent Revolt Is Shaping the Twenty-First Century by Mark + Paul Engler

2. Hope in the Dark: Untold Histories, Wild Possibilities by Rebecca Solnit

3. How to Resist by Matthew Bolton

4. Carpe Diem Regained by Roman Krznaric

5. Get Up! Stand Up!: Personal journeys towards social justice by Mark Heywood

6. No is Not Enough by Naomi Klein

Some long reads I’d recommend;

1. Barack Obama on how to bring about change.

2. Stop Raising Awareness Already

3. Protest and persist: why giving up hope is not an option

If you’re not the read type then here are some ace podcasts to add to this list;

1. Advocacy Iceberg

2. Candidate Confidential

3. Freakonomics Radio

And if you’re able to get to London, then here is an exhibition to check out;

1. People Power: Fighting for Peace at the Imperial War Museum

Finally, you need to add the following blogs to your reading list;

1. Analytical Activism by Alice Fuller

2. The Good Campaigner by Emily Armistead

3. The Social Change Agency

4. Jim Coe

What campaigners can learn from Chris Froome

I’ve been fascinated by politics and campaigns from a young age, but my parent have evidence that I’ve been making Tour de France scrapbooks to follow the annual cycling race since I was 10!

So as Chris Froome wins his 4th Tour de France, I’ve been thinking a little about what lessons campaigners can draw from cycling, and in particular Team Sky (who’ve won 5 of the last 6 races) when it comes to strategy, approach and execution.

1 – Be totally focused on winning – Team Sky come to the Tour de France with one clear objective each year – to win the race. Throughout the 3 weeks that the race moves around France, there are plenty of other sub-objectives to distract – you can win stages, win other jerseys, and more. But Team Sky don’t get distracted by them – they just care about getting their leader across the line in Paris at the end of the race. It’s a ruthless focus on a single goal.

2 – Adjust your plans daily – The old adage that ‘no plan survives first contact with the enemy’ is true in the Tour. There are so many factors the can’t be immediately planned for or predicted – the weather, someone on the team might be injured and not able to race or a mechanical problem. Anticipating what might happen, and then adjusting has been evident throughout the race, when Froome got a puncture, the team member riding alongside him was ready to sacrifice his wheel, while others were ready to pace him back to the front. And because the team have a clear objective, they know what the implications of adjusting the plans are.

3 – Poor planning leads to poor performance – Let me take you to Rodez and the end of stage 14. Chris Froome has lost the Yellow Jersey (worn by the leader of the race) to Italian Fabio Aru, but his team have spotted that the finishing line is uphill and could allow Froome to get some time back on Aru. So the team ride the whole day with the objective of getting Froome to the foot of the climb at the front of the field. Aru’s team don’t and he loses the jersey.

Other examples abound, from having support staff down the narrow roads of the French countryside to give out bottles and musettes (the bags with the cyclist food) rather than rely on going back to the support cars, to exploiting the changing direction of the wind on stage 16 to break the field into a smaller group, to having mechanics double-check everything on the final Time Trial stage because Froome couldn’t afford a mechanical mistake. Team Sky don’t let anything get past them when it comes to being brilliantly prepared. It’s a good reminder for campaigners to apply the same approach.

4- Marginal Gains – Team Sky are built on the concept of marginal gains – the idea that you should be looking for ‘the 1 percent margin for improvement in everything you do’. It’s about being data driven and question everything + challenge existing assumptions. Earlier this year I read ‘The Talent Lab‘ which looks at the approach of the British Olympic team, which shares many of the same approaches as Team Sky.

When members of British Cycling, who work closely with Team Sky, identified that they could improve the power output of there cyclists by making small adjustments to the saddle angles they lobbied for the rules to be changed. Nothing is left to chance when it comes to the approach they’re taking, but perhaps more importantly no question or assumption is a dumb one to asks. For campaigners I think it’s a reminder to look for improvement in every area, but also have a really questioning mindset.

5 – It’s a team effort – Sure it was Chris Froome standing on the top step of the podium in Paris, but he’ll be the first to tell you that he couldn’t have achieved it without the 8 other members of his team. Everyone in the team has a clear role to play across the range and through each stage. Some to support on the flat, some when the race goes up hill. In some way cycling is the ultimate team sport. It reminds me of this list of roles needed in an advocacy movement. You often need all of those roles to be successful.

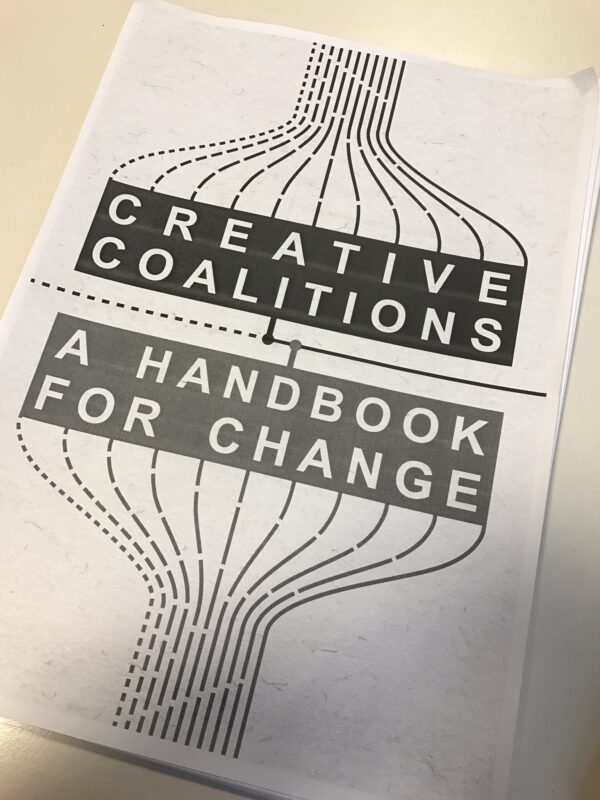

Building Coalition – learning from the best

When it comes to building brilliant coalitions that achieve change, the team at Crisis Action are some of the best in campaigning sector at doing just that. And to benefit all of us, they’ve shared the approach and model they use in Creative Coalitions – A Handbook for Change.

I’m passionate about the importance of coalition campaigning, and it’s something I’ve written about before on the blog, but listening to Nick Martlew, author of the guide and UK Director of Crisis Action speak when he came to the Save the Children office a few weeks ago, I was struck that there are some characteristics and approaches that epitomise highly effective coalition builders that we can all learn from.

1. Strive for excellence – coalitions can often fall into a ‘lowest common denominator’ approach, where you start out by considering what are the asks that everyone can agree on, rather than what is needed to deliver change. For Crisis Action that’s the wrong approach, they start by asking what’s the outcome they are looking to achieve and then ask who they need to involve to make that happen. Work to build together a critical mass of individuals or organisations who have a shared view of how a change will happen.

2. Thrive on feedback – you can only improve if you are actively asking others if what you’re doing is or isn’t working. See feedback as a ‘gift’ and actively seek it out from those you’re working with. It might not always be comfortable received but it invaluable about making you more effective. Be generous is sharing it with others.

3. Keep ‘other’ people in the game – if you’re building a coalition that isn’t going to involve everyone that doesn’t mean you have to ignore them or cut them out. Keep others informed of what’s happening, draw on the insight and knowledge they have – you never know when their insight or connections might come in useful later down the line. Share the insight you have.

4. Always talent spot – keep asking does the tactic your delivering do enough to solve the problem. If it does bring together the best people that can help to deliver that. Crisis Action always asks who should be on the team – who are the talented individuals that they need to be seeking out to get involved.

5. Exceptional networkers – be active at building out networks beyond your usual suspects. Spend time asking them for their opinions – share your ideas for plans and tactics with them and get them to give you an honest assessment of it the tactic is likely to bring about the change you’re looking to achieve. Ask contacts in your networks for ideas of what they think is likely to make the difference.

6. Be Servant Leaders – deploy ego wisely, remember that the cause or the goal matters more than an individuals profile. But that doesn’t mean being un-directed, Crisis Action encourages the principle of ‘democracy of ideas but a dictatorship of delivery’ ensuring leaders are effectively and rapidly bringing the best ideas to life, and delivery is kept on track.

7. Risk Takers – not in a cavalier or reckless way but they’re calculated gamblers who’ve asked around for evidence of what is likely to have the biggest impact, asking informed targets directly what would happen if they attempted specific approach, and then make the calculation about if it’s an opportunity that worth pursuing. That means it’s as important to learn from failure when things don’t work out as it is from success.

8. Seek efficiency – working in coalition often with high costs (I’ve written about what economics can teach us about working coalition). Great coalition builders seek to actively lower the transaction costs of getting involved. They look to find efficiencies that help to keep others involved.

9. Compulsive chroniclers – Write down everything that happens that suggests you’re having an impact – don’t just leave it to the evaluations. Crisis Action have an ‘evidence of change‘ database which helps to capture all the seemingly small changes that those involved in the coalition are seeing which often add up to the big impact.

For those that want to learn more about the report here is a useful summary, and Jim Coe (as always) has done a fascinating podcast with Nick.

Up all night – questions about the direction of campaigning

Occasionally I find myself wide awake in the middle of the night (tip here – if you ever find yourself in the same situation put on Radio 5, you’ll get to experience Up All Night, one of the best shows on the radio) and I find it’s (sometimes) the time to consider some the big questions about campaigning.

In the past few weeks, I’ve had the opportunity to attend a few events where I’ve been able to wrestle with some of the big questions that Campaigners are facing into. It kicked off at a discussion as part of the Sheila McKenchnie Foundation Social Change Project, then I got to hang out with some of the team at The Good Lab, before finishing up at CharityComms post-election event for campaigns leaders.

So lots of good conversations, but what are the big questions about campaigning that are keeping me awake at night? Here are a few I’d suggest from listening to conversations in the last few weeks;

1. What’s the future of digital campaigning? We’ve all dived in wholeheartedly to embrace the opportunities that digital campaigning provides to win change and increase our supporter base – and seen many successes as a result, but as organisations find it harder to mobilise the numbers needed to win change, while acquiring new supporters is proving harder to do for many – impacted I think by the wider conversation about charity preferences. So if the future isn’t in list growth and petition inflation is starting to fatigue many of our targets, then what is the future approach? How do we harness a digital first approach to ensure we have real impact. How do we embrace the way that digital has transformed and democratised campaigning for so many?

2. What does true collaboration look like? We all know that unusual coalitions secure change, and many of us are actively working with others in our campaigns. But given the scale of the challenges that we face, and the limited resources that we have, do we need to consider deeper forms of collaboration? That could be around building shared tools, or finding shared narratives that we can all use beyond single issues. But beyond that what does collaboration look? What’s the role for bigger and more well resourced campaigning organisations to support individuals and movements that are being established?

3. Do we even know the edge of our bubbles? We are increasingly more data driver in our campaigning. We segment based on what you’ve done previously and we aim to target individuals we believe are most likely to take, but are there limited to being data driven, and does it just keep us in our bubble without realising what’s happening outside it. How do we rediscover the skills of listening and adapting to what the external world is telling us. Everyone marveled, for a time, at what Kony 2012 achieved, but that was because they’d sharpened their message by getting out at the coal face and giving hundreds of talks to their target audience of young people.

4. Do we worry enough about our opponents? It’s perhaps a result of how much campaigning has been professionalised, but how munch time are we actually thinking and anticipating our opponents? If the root of the word campaigning comes from the military concept of ‘taking the field’ – as troops moved from the safety of a town or fort into a field for battle – do we need to grow more confident about defining and naming our opposition? Is it OK to put no limits on who is on ‘our side’ and see campaigning as simply a skill like IT programming, or do we need to be clearer on calling out who our opponents are? In politics, opposition research is a key part of any professional operation, but while we devote resources to define our power mapping, should we do more to understand what making our opponents tick?

5. Are charities the best vehicles to deliver social change? I was struck by a comment at one of the sessions about how we need to do more to create organisations that are able to bring about change. Do our structures and approaches actually prevent us for responding in the ways that we need to?

As Naveed from Results observes ‘Recent mobilisations channelling public concern have been far more organic; not leaderless or disorganised, but working perfectly well without a top-down structure. Successful movements allow people to do their own thing, based on a central idea or goal that fires their imagination, but doesn’t tell them what to do. Look at the way people came together around the Manchester terrorist attack, the Women’s Marches, Black Lives Matter, or the Refugees Welcome movement. Only in the latter have NGOs played any kind of a role, and it seems that we haven’t yet properly woken up to the reality of how people organise around causes today.

And if we do have a role to play, and I think we do, how do we adapt to respond to the times we’re in and the approaches we’re finding are successful.

6. Where does change happen in the new political context? If we’re likely to see a period of political uncertainty, with a Parliament focused almost exclusively on Brexit, and all of the parties having their own internal challenges, how do we adapt as campaigners? Is now the time to invest in long-term attitudinal work that needs to be undertaken, ensuring support among politically key groups. In Parliament, should we continue to look to build support from across parties, or utilise the tiny majority that the Government has to play parties off against each other?

Just a few questions I’m grappling with – what are the questions about campaigning that are keeping you awake?