The coronavirus pandemic is changing our lives, but what scenarios might we want to consider about how the pandemic will change our approach to campaigning?

Using the 2×2 Scenarios approaches from Save the Children’s Strategic Foresight Toolkit: Making better decisions, I’ve had a go at creating four contrasting scenarios to help to debate how we might need to change our approach to campaigning.

Normally, you’d use this tool to look at scenarios for the next 10+ years, but given the current situation, this feels like a useful tool for the coming months (and even as I’ve written them they change!).

Importantly these are not predictions, but rather they aim to offer interesting images of the future. My hope is to use them to explore and prompt discussions and debate with colleagues, but I’m sharing here should they be useful for others.

I used these four possible scenarios from Zukunftsinstitut to help get my thinking going, and this from Nesta is also helpful in highlighting some key trends.

Scenario 1 – A closing space

The public is reluctant to gather together for protest or marches as a combination of restrictions on unplanned public gatherings continue (there are different rules for established sporting fixtures), and the ongoing messages about limiting social contact.

Parliament puts limits on the size and scale of events that can be held to no more than 50 or 100, making lobby days or similar at Parliament hard to organise, and ongoing guidance about public gatherings and traveling on public transport makes bringing smaller groups of campaigners together in person harder to do.

Many national and local newspapers have closed during the COVID-19 due to a combination of advertising revenue and circulation of newspapers has fallen to unviable levels – this has removed important opportunities to hold decision-makers to account but to also amplify local views. Most of us now get our news from social media influencers or increasingly partisan online news sites.

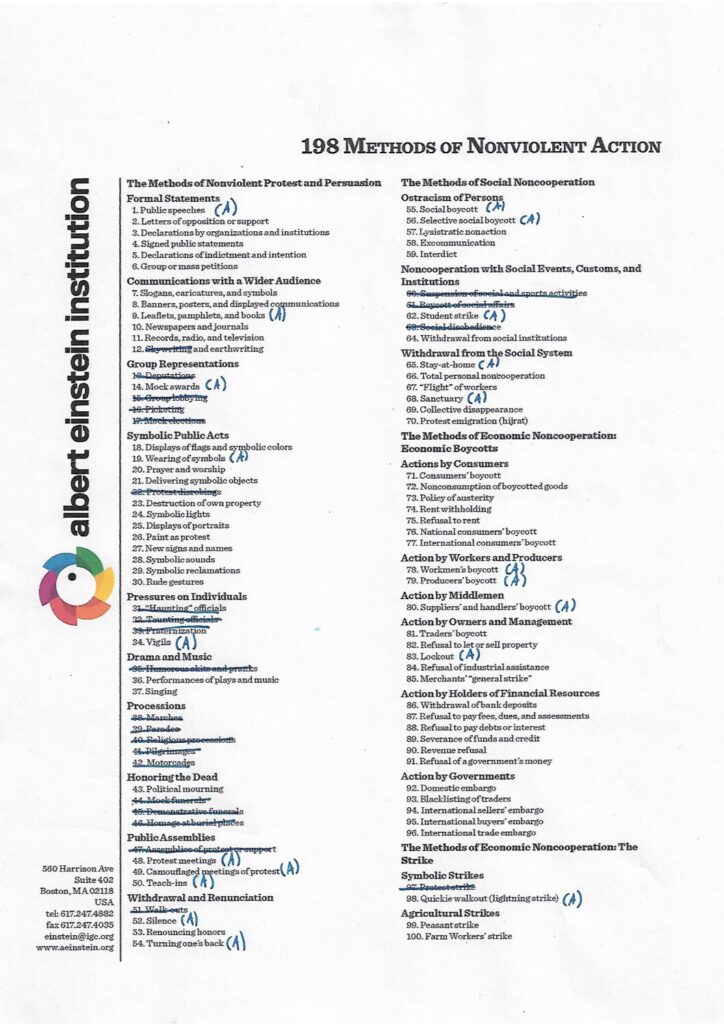

Some governments are using the pandemic to place further restrictions on the operations of civil society organisations and using it to further restrict the ability to advocate and influence. Campaigners have to learn from those movements that have thrived and survived under hostile governments in the past.

Scenario 2 – Back to the future

Parliament returns, with the Conservative government and its 100+ seat majority in Parliament. The government has to focus on an economic agenda that it didn’t anticipate when it was elected, as the country has fallen into a deep recession, but it was seen to be doing an effective job by most of the pubic during the crisis, who are thus largely supportive of their policies, including cutting back some of those introduced during the crisis. Brexit is back on the agenda, but a secondary priority to managing the economic impact of the crisis.

Many MPs and decision-makers fall back on the method and approaches they used – citing the desire to want to show that we’re ‘returning to normal’ as a reason to drop the approaches they’ve taken during the lockdown. The virtual Parliament has come to an end.

We’re waiting for the US presidential elections, but the ongoing dysfunction in global institutions have continued to stall international cooperation. The rearranged COP summit on climate in Glasgow is seen as a moment where the UK government will aim to demonstrate that the country is moving forward – putting the focus back on the climate emergency.

Scenario 3 – A digital leap forward?

Remote working from home becomes increasingly normal for those who can, with that adjusting the way that we also connect with businesses and institutions, with the expectation that we’ll be able to video call, someone, as opposed to just a voice call – including campaigning groups and charities.

This move to digital is also subtly changing the nature of local community, with the result of Mutual Aid groups being that individuals are more connected to their immediate neighbors through community WhatsApp groups or similar, as over 30% of have been part of a local community response group – but we’re less engaged in wider institutions, especially those which haven’t been able to adjust to the new digital expectations – this further narrows the perspectives and opinions many are exposed to.

Through lockdown, many MPs and decision-makers have moved to new methods to continue to engage with, for example, virtual surgeries, or being more accessible through social media is a norm. That continues with MPs increasingly using the approaches their lockdown approaches for ongoing interactions – that opens up possibilities and opportunities, for example, more and more digital roundtables with MPs or Ministers, but also creates a further digital divide for those who do not have access to computers or reliable data connection. Elements of the virtual Parliament continue – like electronic voting.

Scenario 4 – A great shake-up

As with past public health crises, COVID-19 sparks a desire from the public for far-reaching reforms, securing many of the policy changes that were announced during the crisis, but also more, as a result of a government ‘in the market’ for other ideas and approaches.

Think tanks and other policy institutes are in demand, with requests for new ideas to help to respond to the social, economic and health crisis that coronavirus has caused. Policies that just a year ago were thought to be unrealistic or improbable are now considered.

The connections made in communities through mutual aid groups continue, with a closing of the ‘empathy gap’ as individuals reflect on the importance of having strong community ties. This leads to a growing interest in campaigning and advocating on local issues – with a big focus on councils and mayors as local bodies that are seen to be most responsive. As a result, further devolution gives mayors and councils more power to make decisions and enact policy.

What do you think? What seems likely or unlikely? What might this mean for your approach to campaigning?