Settle in with a cup of tea, here are 14 great reads (in a rough order of how much I enjoyed them) that I’ve shared during 2014 that a worth a read.

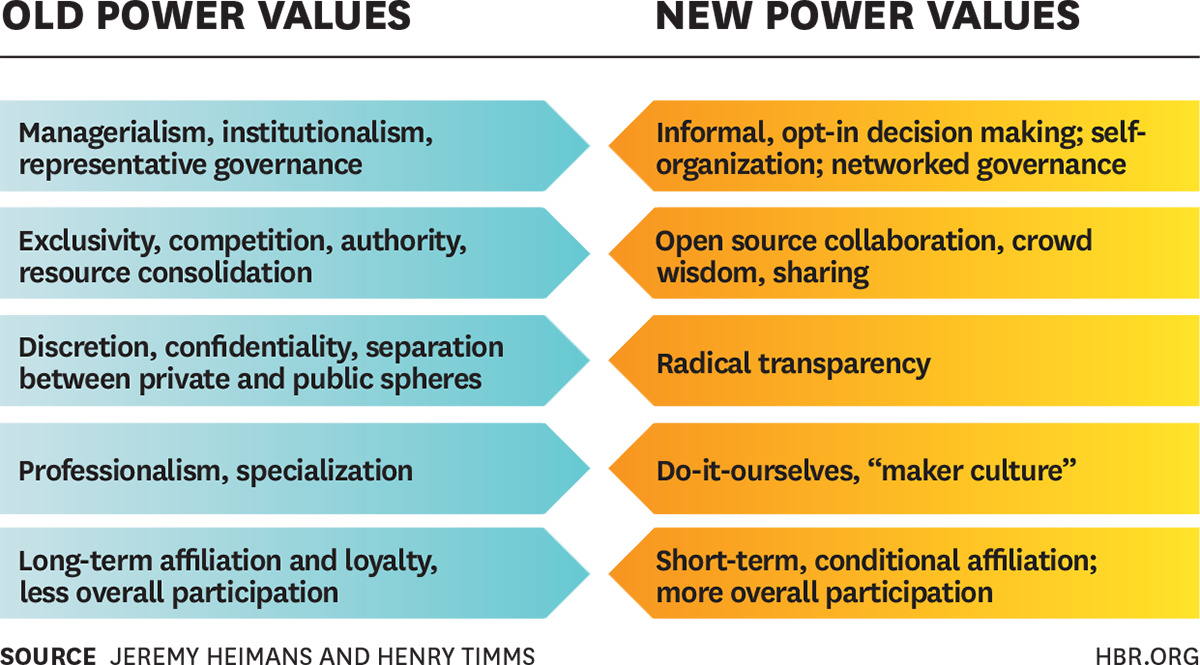

1. Understanding New Power – brilliant from Jeremy Heimans and Henry Timms on how the world is changing. A must read (great summary in the graphic above).

2. Changing Trends: New Power, Neuro-Campaigning and Leaderless Movements – just love this paper on key campaigning trends from Hannah and Ben.

3. Purpose Driven Campaigning – 40 key principles for growing social movements drawn from Purpose Driven Church.

4. When the pillars fall — How social movements can win more victories like same-sex marriage – brilliant look at how same-sex marriage advocates in the US build a movement to win.

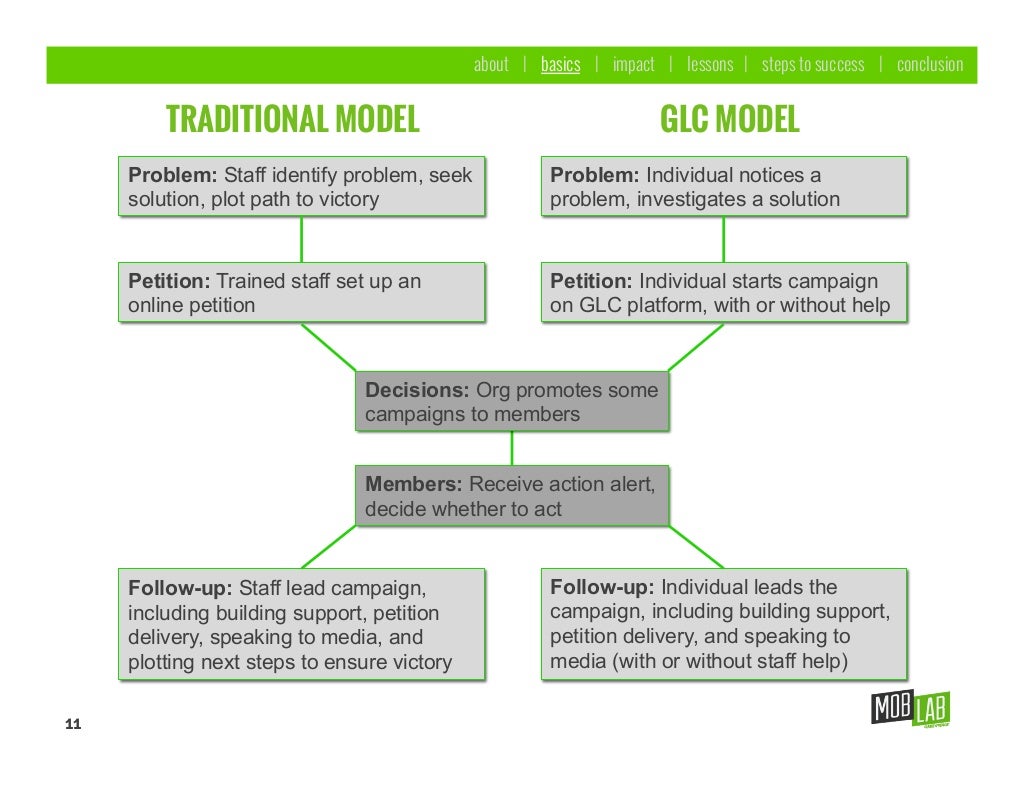

5. Grassroots-led Campaigns: Lessons from the new frontier of people-powered campaigning – brilliant MobLab report full of wisdom and insight of the people at the cutting edge of grassroots-led campaigns (GLC model in the graphic above). Basically anything MobLab writes is brilliant.

6. From fired up to burnout: 7 tips to help you sustain a life committed to social justice – offered without comment.

7. 6 things today’s breakout campaigns get right – great insight from the always brilliant Jason Mogus

8. “More of an art than a science”: Challenges and solutions in monitoring and evaluating advocacy – also enjoyed this by Jim Coe.

9. Stonewall’s secrets of successful charity lobbying – top tips from one of the best (also learning from Greenpeace here).

10. From Petitions to Decisions – how change.org is continuing to innovate.

11. Inside the Cave – a look at the digital and technology behind the Obama 2012 campaign (and here is more on how the campaign used twitter)

12. The Art of Coalition Campaigning – brilliant set of reflections from Ben Niblett.

13. 14 lessons from the Scottish referendum – useful reflections from the UK political event of the year (more here)

14. Rage Against the Machine – Lessons from Guzzardi–Berrios Race – how a 26-year-old former journalist organised to get elected in Chicago. Great lessons about working with the grassroots (and here on how to lose your seat when your a high-profile US politician).

Tag: learning

5 lessons from the AV campaign

Paul Waugh has a great article on ‘Who won the AV digital war’. It’s full of interesting learning about what worked and what didn’t.

In short, the Yes campaign (the link is to the Labour YES site as the cross-party site has already been taken down) tried to build from the grassroots, based on the fact that they inherited a list of 150,000 people who were involved in campaigns like Unlock Democracy. It put it’s effort into converting this online support into offline activities, like getting activists to organise street stalls and events (of which 3,000 were organised). I guess by extension it was also hoping that its messages would cascade down from activists to their friends through social networks.

The No2AV campaign didn’t inherit an email list and focused on buying advertising on high-profile websites, reportedly spending the most of any campaign in UK political history on the day of the ballot (the exact figures will be released in the coming weeks when the final spending figures are released) and pushing people to its sites and You Tube page, which worked as the NO campaign registered almost twice as many views of its YouTube channel. According to Waugh a decision was made not to engage on twitter and also placed a greater focus on using text messages as a tool to mobilise supporters to attend events.

Clearly the result of the referendum wasn’t simply about the success or failure of the digital campaigns (you can read more about the politics of the campaign here) but I still think it has some interesting lessons for NGO campaigns especially as Waugh suggests ‘From its hardline attack ads to its press operation and its mass bombardment approach, the No2AV campaign most felt like a mainstream political party. With its activism and social engagement, not surprisingly perhaps, the Yes campaign most looked like an NGO’

Clearly the result of the referendum wasn’t simply about the success or failure of the digital campaigns (you can read more about the politics of the campaign here) but I still think it has some interesting lessons for NGO campaigns especially as Waugh suggests ‘From its hardline attack ads to its press operation and its mass bombardment approach, the No2AV campaign most felt like a mainstream political party. With its activism and social engagement, not surprisingly perhaps, the Yes campaign most looked like an NGO’

1. Digital media needs to be at the heart of any campaign – Both campaigns put digital media at the heart of their approaches by ensuring the appropriate lead staff attended key strategy meetings. Waugh says ‘MessageSpace’s Jag Singh, an early appointment as Director of Digital Comms for No2AV, was ’embedded’ in the highest level of the campaign, attending all of their 8am morning meetings for example’ and suggests that same was true of the Yes campaign.

2. You can raise money from online campaigning with the right ask – The Yes campaign generated £250,000 from small donations (the average was £28) in the course of the campaign. A good example of a timely ask to the right audience can raise money as well as lead to activism.

3. Let’s not forget mobile phones as an organising tool – It’s interesting to note the use of this by the No2AV team to mobilise supporters. A few weeks ago I heard that research has shown that most text messages are read within 15 minutes, the same clearly can’t be said of emails where a 10% open rate is considered ‘good’. Should NGO campaigns be investing more in collecting mobile numbers that can be used to inform activists of key events or actions?

4. You need to reach out beyond the usual suspects – Was one of the reasons that the No2AV approach work so well was that in buying on-line marketing it reached beyond the usual suspects on the day of the election, whereas Yes campaign activists were speaking in an ‘echo chamber’ where they were simply sharing their tweets and messages to friends with similar views who were already inclined to vote Yes. One status update on my Facebook wall perhaps summarises this problem well ‘if my Facebook feed is anything to go by, the Yes vote is in the bag. But then, I don’t think I have a very proportionate representation’

5. Decide what to do with the data afterwards before the event – Waugh highlights a problem common to many in coalitions, both campaigns have built significant e-lists but it isn’t clear what to do with that data now. A good reminder of the need to discuss this before your build your list.

Do you agree? Did the politics of the situation mean the digital strategy wasn’t going to make a difference either way?

Can we ever hope to influence Beijing?

China officially became the second biggest economy in the world last month overtaking Japan for the first time, and while the influence of China over most international processes has been clear for a long time, can we ever expect to influence the Chinese government?

China officially became the second biggest economy in the world last month overtaking Japan for the first time, and while the influence of China over most international processes has been clear for a long time, can we ever expect to influence the Chinese government?

Both Oxfam and Greenpeace must believe so, as they’ve expanded out of Hong Kong to open offices in Beijing and include advocacy as one of the priority activities that they’re involved.

However putting the words ‘China+advocacy’ or ‘Influencing Chinese government’ doesn’t come up with many useful results.

No doubt that’s partly down to the lack of documents in English and the unique political system in the country. But even so the material about doing so seems to be very scarce, so I hope that this post will be an opportunity to learn from others about how organisation have gone about starting to think about the opportunities.

Here are two example of advocacy in or towards China that I’m aware about.

What others can you add? And what, if anything can we learn from them?

Greenpeace East Asia – Last year, Greenpeace alongside ad-agency Ogilvy turned 80,000 pairs of used chopsticks into trees which were displayed in Beijing in an attempt to highlight the impact of using disposable chopsticks was having on the countries forests, and encouraged people to sign a pledge to carry around their own pair of chopsticks. However, the focus of this campaign was on raising public awareness and personal action rather than political action.

Avaaz – In 2007/08 the online campaign movement repeatedly asked its supporters to send messages to the Chinese government over the situation in Burma. It collected an impressive 800,000 names on its petition which called for an end of the oppressive crackdown on demonstrators, including placing an advert in the Financial Times asking ‘What Will China Stand For?‘.

For me, these two examples raise as many questions as they answer. Do our traditional models of ‘northern’ advocacy need to change if we want to be effective in China? Is ‘quiet’ advocacy more likely to work than public mobilisation? What’s the role of the international media? Does China worry about the way its perceived by others around the world?

#SaveOurForest – a campaign reader

Put a note against Thursday 17th February in your diary, as it marks an important moment for campaigning in the UK. The coming of age of 38 degrees.

Today, the online campaigning movement celebrated as it notched up its most high-profile victory yet, the government make a U-turn and abandons its plan to sell of the forests (watch the announcement to Parliament here).

Lots has already been written about the campaign, and I don’t think I can add much at present, here is a reader of some of the top articles which explore how the campaign unfolded and the impact it’s had.

1. The Guardian explores the important role that social media played in the campaign in Forest sell-off: Social media celebrates victory

2. Johnny Chatterton, from 38 degrees writes for Left Foot Forward about the size of the campaign, with his boss, David Babbs, Executive Director saying ‘Forest sell-off U-turn is a victory for people power‘

3. Chris Rose wrote last week about how ‘Clicktivism By-passes Inside Track To Harry Potter Forest‘ and also the roots that this campaign had in previous battles for forests around the country.

4. Jonathan Porritt criticised the larger environmental NGOs by not supporting the campaign of ‘collective betrayal‘ on his blog, while this blog argued that the campaign had highlighted some of the challenges large NGOs faced in responding to an issue with the agility an organisation like 38 degrees can.

5. The Sunday Telegraph ran many articles, demonstrating the broad support the campaign had ‘Save our forests, say celebrities and leading figure’ something that was clearly important in the victory.

6. But not everyone has been so kind, with Anthony Barnett at Open Democracy, suggesting that 38 degrees shouldn’t take all the credit for the campaign victory, following up on an earlier post challenging them not to compete but campaign with others.

7. But the last word picture should go to cartoonist Steve Bell in today’s Guardian.

What other articles have you read that help to explain the story behind the campaign? Why did this campaign work when so many others haven’t?

When a NGO admits it’s wrong. WWF and it’s (non) involvement in the Save Our Forests campaign

It’s not often you see a big NGO come out in public and admit that they got something wrong.

It’s not often you see a big NGO come out in public and admit that they got something wrong.

So it’s great to see WWF put out a statement today effectively apologising for its lack of public action and clarifying its stance on UK forest sell-off in response to some harsh criticism it’s received in the press this week.

It’s a spat that started in the Guardian on Monday when environmentalist Jonathan Porritt accused major charities, including WWF, RSPB and the National Trust of “collectively betrayed” for their failure to support the grassroots campaign that has grown in the recent weeks to halt the sale of English forests, while Polly Toynbee put the boot in on Tuesday accusing green groups of ‘keeping their heads down over selling off forests’.

Today, WWF have responded with an excellent statement on their website confessing that they should have done more from the start.

Porrit stated “There have been no statements, no mobilisation of its massive membership, no recognition that this is an absolutely critical issue for the future wellbeing of conservation in the UK. Nothing”.

Suggesting that the lack of action had “made themselves look foolish and irrelevant as one of the largest grassroots protests this country has seen for a long time grows and grows without them – indeed, despite them.”

There is no doubt that the campaign mounted by 38 degrees and others has gathered a huge amount of momentum in a short time, it’s petition has just gone over the half a million mark.

Perhaps most interestingly, it feels like it’s not only the ‘usual suspects’ who are signing on. A non-campaigning friend of mine posted the link to the petition on Facebook tonight encouraging people to sign, and the Observer reported of the opposition of many land owners last weekend.

So I’m impressed to see the response from WWF today, who write of the statement that ‘It’s fair to say this is a bit overdue as loads of you have asked us what we’re doing about the proposed government sell-off (or long-term leasing) of UK forests’

Going on to explain ‘Not having much of a history working on UK forests, we did most of our work behind the scenes and focused our public firepower on issues like illegal logging via our ‘What Wood You Choose?’ campaign. We are working with peers getting an amendment tabled in the House of Lords and had questions asked in parliament, but to be honest we did precious little in public’ (emphasis mine)

In time it might be right to ask if criticising environmental NGOs in such a public way was the right approach by Porritt? As an unnamed source in the original article says ‘Rule one of clever campaigning is that you don’t criticise members of your team, at least not in public’ and WWF say they’ve been working on this behind the scenes.

But for me this spat has once again highlights some of the challenges that the more ‘traditional’ NGOs need to address in their campaigning.

1. Agility

Movements like 38 degrees are so well placed, because they can respond within hours not days. They lack the restrictions of charitable status and often no desire for a seat at the table in ongoing consultation. Combine this with a phenomenal e-mail network mean that they can be ‘first to market’. The challenge that many ‘traditional’ NGOs face is that they’re not set up to turn around a response in the time that online campaigns like 38 degrees.

No doubt heated discussions have been happening at all the NGOs that Porritt choose to criticise (as you can see implied by the response from WWF), but the very nature of these organisations mean that multiple departments need to be involved and opportunities and risks needs to be carefully calculated, but that whole process takes time, and internal compromises often have to be negotiated. In this digital age waiting even 24 hours to respond or act can be too long.

2 – Collaboration

Within a day or so 38 degrees had already collected the first 50,000+ names on its petition, and then you have to ask how much value there is in starting a second competing petition. This for me is the second challenge are traditional NGO prepared to ‘brand’ and ‘profile’ aside and collaborate for the common good when situations like this arise?

Would the NGOs named be prepared to promote the 38 degrees petition assuming they agreed with the essence of what it was calling for?

On this regard I’ve got a huge amount of respect for WWF for saying in their statement ‘To their great credit, 38 Degrees organised a massive public response (sign here if you haven’t already)’ but no doubt that line will cause some anxiety in the organisation as supporters are encouraged to share their valuable data with others.

Collaboration is essential, and to do it well campaigners need to recognise the different roles and approaches needed for effective campaigns.

Save our Forests is no different, surely it’d be of huge value to have organisations with both years of experience in nature conservation joining the campaign and impressive contacts within Parliament to be involved. But to do that requires someone to initiate the collaboration, and in situations like this perhaps it’s not clear who that should be.

3. Accountability

Perhaps it wasn’t Porritt’s criticism and the Guardian articles that lead WWF to clarify their position. The statement from WWF certainly indicates that they’ve also been hearing complaints from supporters saying ‘The scale of passion around this issue has led to a lot of emails as to WWF’s role’.

This case seems to be another example of the increasingly complex relationship that organisations have with their supporters. The tools of collaboration and campaigning aren’t just in the hands of a few professionalised campaigners, they’re available to supporters to lobby the organisations they belong to. It also shows that many campaigners are active in more than one campaigning network.

So congratulation on an excellent response from WWF, a response that already seems to be yielding appreciation from supporters with one writing;

Thank you. As a WWF member and supporter of the Save Our Forests campaign, I’m very glad you’ve joined the campaign. The statement above is everything we could have hoped for.

Now I’m left wondering if we’ll see the National Trust and RSPB come out with a statement in recent days.

Lists of people who matter

Regular readers of this blog will know that I’m a big fan of lists. Although I’m not a natural Daily Telegraph reader, their annual profiles of the top 100 most influential people in each of the political parties is an invaluable resource when it comes to planning routes to influence.

100 Most influential Left-wingers – 1 to 25, 26 to 50, 51 to 75 and 76 to 100

100 Most influential Right-wingers – 1 to 25, 26 to 50, 51 to 75 and 76 to 100

Other lists produced in time for Conference season include;

– Left Foot Forward – most influential left-wing thinkers

– New Statesman – 50 people who matter

Has anyone else found any useful lists?

Gurkha justice

The right person to front the campaign – Lumley has also proven herself to be an effective political operator holding impromptu press conferences and using her profile to secure meetings with politicians from all parties to drive the case. As this profile in the Observer explained it was not only asking the actress who most people recognised and liked helped to give a face to the campaign, but also the personal link that Lumley had with the issue. Her father was a major in the Army who lead a troop of Ghurkha solders, and it meant that she was able to speak from a position of integrity, and appeared to be prepared to invest a huge amount of her personal capital in leading the campaign rather than simply providing a face for a media opportunity before moving onto her next engagement.

Framing the issue correctly – At the heart of this campaign this was a immigration issue, normally something that plays badly with most of the media, but the campaign framed the arguments in clear moral terms, these people had fought for our country with honour. The right thing, the British thing to do was to let those who wanted to come to the UK, the Ghurka Justice website talks ‘a debt of honour’. The campaign picked great examples of heroic soldiers and meant that the press found it hard to do anything but ‘back the boys’. It wrong footed the government who thought that the immigration argument would prevail by proving that a stronger narrative existed.

Involvement of national newspapers -Both The Sun and The Mirror ran a petition in support of the campaign. Collecting tens of thousands of names and demonstrating broad public support for the issue, and showed that while newspapers might be loosing influence when they back an issue they make it hard for the government to ignore.

Building slowly – Although it’s made headlines in the last few weeks, this is a campaign that has been working hard in parliament for over a year building support, both amongst the opposition parties who got the issue to be debated in parliament, but also amongst backbench Labour MPs. Much of this work has happened quietly, but it meant that when the issue came to be debated many had considered the arguments and were prepared to vote against the whip.

Good timing – Undoubtedly luck has played a part in this campaign. The issue was debated at a bad time for the government that had been rocked after a number of potential defeats and PR disasters. It meant the opposition parties saw they could further wound the government and show that they had a better sense of what the mood of the country was.

Ministerial Correspondence

It has long been believed that getting an MP to write to minister is a more effective than sending postcards directly to a government department. Why? Because protocol dictates that a letter from an MPs requires a ministerial response, but how many items of correspondence are government departments getting?

This ministerial statement from last month gives details of the number of ministerial correspondence (letters from MPs and Lords) each department receives in 2008. The top 10 departments and agencies are;

1. UK Border Agency – 51,905

2. Department of Health – 20,242

3. Department for Children, Schools and Families – 15,810

4. Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs – 14526

5. HM Treasury – 14,057

6. Foreign and Commonwealth Office – 10,334

7. Department for Communities and Local Government – 10,227

8. Department for Business, Enterprise and Regulatory Reform – 9,875

9. Department for Transport – 8,393

10. Child Support Agency – 7,313

A couple of others to note included DECC which received over 2,500 letters in the few months after it was created, and DFID which recieved 3,100.

Many of the letters recieved by agencies (like the UK Border Agency where a large number of the enquiries will be individual imigration and asylum requests) from MPs won’t ever be seen by a minister so will have little or no political impact.

Taking out agencies the average government department receives just under 7,000 letters per year. When you divide that between 4 ministers (an average number of ministers per department based on a quick look at this Cabinet Office list) it means that each minister is dealing with about 34 letters each week but many will be signing many more.

This is a useful briefing for civil servants about how to draft responses to ministerial correspondence.

Learning from the Heathrow 3rd runway campaign

John Stewart spoke at the latest CASS Business School Charity Talk event. In a talk entitled ‘Campaigning with Effectiveness and Flair‘.

John is Chief Exec of HACAN, the largest voluntary organisation dedicated to those campaigning on behalf of those affected by aircraft flight paths, and chair of Airport Watch, a broader coalition of organisations campaigning against the issue of airport expansion.

In his talk he unpacked some of the reasons why the campaign was so successful at dominating the discussions and debates around the building of a 3rd runway. I’ve written before about the Heathrow campaign and some of the reasons I think were elements of its success but Stewart provided a first hand account from the inside. The KnowHow NonProfit website, which is linked to CASS Business School, has some excellent resources from the evening (which also includes Brian Lamb’s presentation which I’ll blog about later in the week).

Stewart drew out three main lessons from the campaign and argued that these were also based on things that they’d learnt from previous defeats that HACAN had experienced over Terminals 4 and 5. A good reminder to always learn from campaigns that don’t succeed!

Bring together the widest possible coalition

In previous campaigns, HACAN had drawn together a small number of residents groups and local authorities around Heathrow but the 3rd runway campaign managed to build a much bigger coalition not just of the usual suspects but a much bigger range of organisations, such an environmental groups, direct action groups alongside MPs, local authorities and residents groups.

Stewart said that this strengthened the campaign enormously, but also introduced new issues (climate change wasn’t a central part of the previous campaigns which had focused more on quality of life issues). Stewart shared the tactics that the coalition had used to keep together what must have been a disparate group of people, including regular face-to-face meetings, which meant that people got to know each other on a personal basis.

You have to admire the campaign for managing to bring together local Conservative councillors to direct action activists from Plane Stupid, but Stewart argued that united around a common aim to stop a 3rd runway was the strength of the coalition. The range of tactics meaning that it made it much difficult for authorities to know how to respond because their tactics couldn’t simply be put into a box or be predicted.

Don’t dodge the economic arguments

The campaign realised from its previous defeats that it had to engage with the central issue and argument that the government was using to justify building the runway, that the UK economy needed it. In previous campaigns, Stewart implied they’d focus on quality of life arguments that although important to those involved in the campaign didn’t resonate with decision makers who could suggest that these were the arguments of NIMBYs.

Stewart shared how they commissioned independent research on the economic argument, which was undertaken by an independent and respected consultancy firm which the EU also used, so it couldn’t be immediately dismissed by government as a being written by a pro-environment consultant. The campaign found that this report was vital in helping to counter the central arguments of the government, and convincing the opposition parties to get involved . A good lesson to remember the importance of independent research in supporting your campaign asks.

Engage in pro-active campaigning

Early on the campaign realised its tactics couldn’t simply be limited to working through the official structures that the process would provide, like official enquiries which was its previous approach. Stewart argued that if these processes were effective at changing things they’d soon change the structures, perhaps a slightly cynical approach but the argument that they don’t favour community campaigns who have little of experience of making quasi-legal arguments is a good one.

Instead the campaign focused their campaigning on what communities are good at doing, talking to each other, and mobilising around more traditional tactics like marches and rallies. This was successfully combined with more traditional lobbying using a cross-party group of MPs, and excellent cheap media activities, like flash-mobs at the opening of terminal 5.

At the end of the presentation, Stewart spoke about how the campaign had worked with direct action groups. He argued that they’d been good for the campaign, and an important part of the campaign mix. While the campaign didn’t want everyone taking direct action, they helped to prevent the campaign from easily being boxed by the government. Listening to Stewart talk about the role of groups like Plane Stupid in the campaign, its clear they have a central role, and its fascinating to see how these groups co-existed and even shared platforms with those with much more conservative approaches to policy change.

MPs and digital media

Using supporters to engage and influence MPs remains the core work of many campaigning organisations, and many organisations have chosen to make this easy for supporters by investing in software such as Advocacy Online, but what do we know about how MPs use technology and respond to eCampaigning. Two reports might help.

How MPs use digital media.

The Hansard Society has recently released ‘MPs Online – Connecting with Constituents‘ which explores how MPs use digital media to communicate with constituents. The finding are useful for campaigners, as it gives an insight into what MPs are themselves doing, and provides ideas about how organisations can increase their digital engagement with MPs.

The report finds that almost all MPs are using email, most have personal or party run websites but the numbers using other forms of electronic communications is smaller. Social networking, blogs, twitter and texting is used by less that 20% of MPs. The overall picture seems to be that MPs, much like many campaigning organisations, have started to adopt digital media as a way of communicating out to constituents, but less have been able to make a leap into using using web 2.0 tools which might help to ensure a more meaningful conversations with constituents.

Their are some interesting differences dependent on party membership (Lib Dems are the positive about digital media, Conservative the least) and age (younger MPs are more likely to use it, so as older MPs stand down we’re likely to see a bigger take up of digital media ), but little difference dependent on marginality of seat. The report suggests that their is potential for greater engagment and closer ties in the future.

MPs also make useful observations saying that email has been great for them to communicate with constituents but the immediancy of the tool means that people often assume that they’ll be able to engage in a ongoing discussion that MPs simply don’t have time for, indicating that their office staff often struggle to cope with the volume of emails recieved (an increase which hasn’t been accompanied by a fall in the number of letters) , and the challenge of identifying if the correspondent is from their constituency.

Attitudes towards eCampaigning

In 2006, Duane Raymond at Fairsay was comissioned to carry out some reasearch about MPs attitudes to eCampaigning, the whole report can be read here.

Although its a few years old, the findings from the Hansard Society would indicate that many of the key learning probablly still remain true. The main findings of the report is that every MPs is very different in how they respond to and engage with eCampaigning, but that most organisations still offer their campaigners a one-size fits all approach to commnications.

This means they’re not having the biggest impact they could and the findings encourage organisations to be much more savy at how they segment their communications to MPs, for example by segmenting the message that they ask supporters to send. Many MPs report that quality is as important than quantity when it comes to messages.

Another finding that stands out is the need to show that MPs that the person contacting them is actually from their consituency. The internet may have in many ways removed geographical barriers, but they are still of considerable importance to MPs.

Some conculsions

For me both reports indicate that it makes sense to have an online campaigning presence, but also reinforces that this shouldn’t simply replace more traditional low tech campaigingng method but should work in tandem.

Organisations should remember that n individually composed letter (or email) is better than an automated one – many organisatiosn know this, but perhaps more needs to be done to encourage people to spend the extra 5 minutes to write it.

Individual constituency level activists will always have a value, the MPs indicate that those people who have the time to write a hand written or visit an MP are ‘worth their weight in gold’. Organisations should do all they can to encourage, support and inspire these people.