I went back to university a few weeks ago – it was really fun to be able to go back to UEA in Norwich where I studied and share as part of their annual ‘Working in Development’ forum.

It was a bit of journey down memory lane, and as much as I enjoyed sharing some of the journey I’ve been on since graduating I also spent much of the day feeling increadibly thankful.

Thankful that I get to do a job that I love everyday – even on the not so good days, thankful for the many managers, colleagues and mentors who’ve invested in me during my career, and thankful to work alongside such great colleagues on work that I feel really passionate about.

I was asked to share one some of the key skills that I’d picked up since graduating – because lets be honest I’m not sure how much of my Microeconomics for Development course has come in handy on a day to day basis.

So I reflected on some of the atributes that I think are important for anyone looking to start a career in advocacy and campaigning – and how you could go about developing those as part of your studies.

But I don’t think you stop needing to develop those when you stop you graduate, so thought that it might be useful to share my thoughts – not least as much as a challenge to myself to keep exploring these areas.

I’d love to get readers thoughts on what the most important areas for campaigners to focus on developing.

Curiosity – I think a curiosity about how change happens is one of the most important qualities for a campaigner – you’ve got to be interested in what’s happening around you and why.

Duncan Green writes that change isn’t like baking a cake, where you can be assured of the same outcome if you follow the receipe. You can follow the same steps, but come out with a totally different outcome – to be an effective campaigner you need to be curious about asking what’s happening to get the outcomes you’re getting.

Duncan talks about how change is complex, and as this rather ace article from Sue Tibballs at the SMK Foundation argues it’s vital that campaigners learn to dance with the system and embrace what they seeing happening around them.

Lots of the work and thinking on this is based on the writing of Donella Meadows who really pushed the idea of systems thinking, but it feels like in the times that we live in, that embracing approaches that allow you to take advantage of the uncertain times we live in are critical.

So campaigners need to;

1. Become familiar with the ideas of complexity, systems thinking and ‘dancing with the system’ – to do that I’d strongly recommend starting with Sue’s blog or Duncan’s book.

2. Continue to explore the same issues from different perspectives – look to see what clues thinking about the issue you’re working on from another viewpoint might highlight.

3. Look beyond the now conversation at what’s being discussed at the fringes and margins. Do they point to approaches and trends that might over time become more mainstream. I found this graph really helpful when thinking about this.

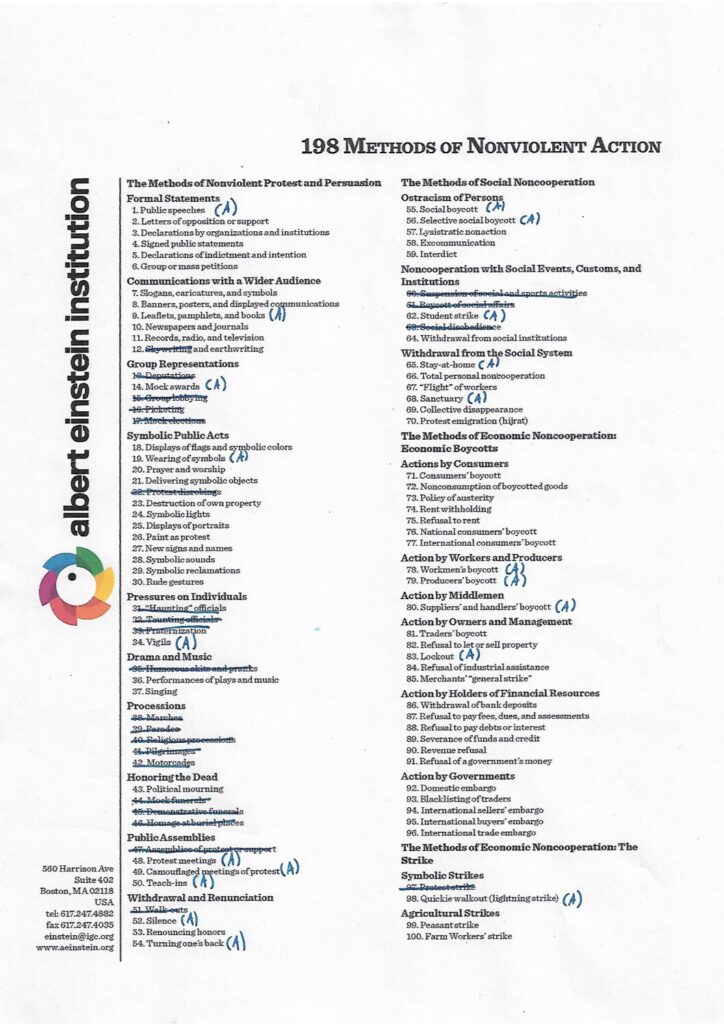

Communication – an obvious one perhaps, but if campaigning is about building support for your ideas, equipping yourself with an understanding of the tools and perhaps as important approaches that lead to effective communications matters.

As I suggested on Twitter a while back, we’ve all moved away from talking abou raising awareness to shifting the narrative, and there is something important in that approach to me – it’s accepting that people don’t just act on an increased understanding of an issue, to move them to act or support an issue it can require a more nuenced approach.

That it’s about a recognition that the way we frame our messages, the messengers who present those messages, the images and visuals we use, the story we create and repeat across our communication channels and much more. Thankfully there are lots of brilliant people out there thinking about how campaigners can win change.

So if you’re not alread I’d suggest;

1 . Reading up on some the brilliant and interesting work that people like Nicky Hawkins, the team at Common Cause, or the Centre for Story-Based Strategy. They all take different approaches but put thinking about how we communicate at the heart of change.

2. Expose yourself to how those on the political right use frames and narratives so successfully – learn from their tactics. Words the Work by Republican pollster Frank Luntz is a little dated, but it’s a good primer if you want to get started.

3. Experiment with and build skills in using different platforms – I’m struck how important visual mediums (films. photos and graphics) are now for communications – I’ve just got An Xiao Mina’s ‘Memes to Movements: How the World’s Most Viral Media Is Changing Social Protest and Power’ on my reading list to prove that point. Perhaps its time to turn this blog into a vlog?

Collaboration – As campaigners we know that change rarely comes from the work of a single individual or a single organisation, it comes as the result of collaboration across individuals and organisations – sometimes in unlikely or unexpected partnerships that are held together just by a desire to bring about that specific change, but building those partnerships requires those who can build trust,

So preparing for the talk I got to read one of my favourite papers on leadership again Margaret Wheatley’s ‘Leadership in the Age of Complexity: From Hero to Host’ which suggests that as we move into a world of complexity leadership isn’t about the old model of command and control, with the leaders as the hero with the answers, we need leaders who act as host, accepting that they don’t have all of the answers, and one of my messages to the students was to start to invest in the type of leader you want to be now.

It’s easy to think that you only become a ‘leader’ once you start to manage people, budgets and projects – but I just don’t think that’s true I think you can start to invest in being a leader wherever you are;

1. Reading Wheatley’s paper is a great place to start – every time I go back to it I come away with something new to think about and reflect on in my approach.

2. Reflect on the qualities of good collaborators – this is a useful SSIR article from a few years ago with some of the attributes of those who are good bridge builders.

3. Learn from past movements – just because the context was different it doesn’t mean we can learn from the approaches they took to bring together others. The Changemaker podcast has been one of my favorite for learning more about this.

Control – so this was pushing the C theme a little bit, but the final area where I think all campaigners need to be thinking about is who is in control – who has the power.

I’ve been increasingly interested in the ideas of John Gaventa and his Power Cube over the last few years – it builds on the work of Stephen Lukes that I was introduced to when Hahrie Han came across to speak a few years ago – and got me thinking about power, but there are others who’s work on power is worth reading like the four ‘expressions of power’ developed by Just Associates, or New Power/Old Power developed by Henry Timms and Jeremy Heimans.

Gaventa writes about the 3 dimensions to understand – place, space, power – it’s the last one that I’m most interested in, where he argues that power can be visible – the obvious powerholders, hidden – the barriers which may keep people from engaging, and invisible – the norms, cultures or assumptions that go unchallenged.

Campaigners often just look at who has visible power but digging into that and looking at the invisible and hidden power in any campaign can help lead to different or new insights – thinking about it has really helped me to reflect more about who has control and thus power.

So spending time really understanding ;

1. Understand some of the theories above and look to apply that the next time you look to do some power mapping.

2. Start to think about more than just who has visible power when developing strategies – the diaries of and interviews with those who are no longer in power can often be revealing on this.

3. Identify the opposing forces to your issue – and deconstruct how they’d approach your campaign. What does that tell you?