“It is more powerful to recruit unexpected allies than to galvanise the usual suspects”

One of the 5 lessons that Justin Forsyth shared during his ‘Changing the Changemakers’ lecture at the RSA last week reflecting on his time leading Save the Children UK.

I’d strongly recommend watching the whole lecture (or reading this article which summarises his lessons) because it’s packed full of useful insight about how change happens from someone who has been at the forefront of achieving it both outside and inside government, but the lesson about unusual alliances is one that resonated with me the most.

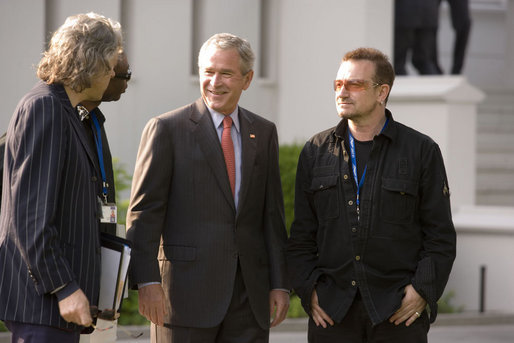

In his lecture, Forsyth cited the example of how the Religious Right in the US joined forces with Bono to persuade President Bush to massively increase the contribution that the US government made to fund the global response to HIV/AIDS and also the work that Save the Children have done with GSK – a company he had personally campaigned against in a previous role – in reformulating an antiseptic found in mouthwash into a gel that prevents serious infection of the umbilical cord, a common cause of death for newborn babies in poor countries.

Both show the power of unexpected alliances. This is a lesson is something I’ve written about before. But thinking about building unexpected allies also challenged me to ask are campaigners today doing enough to build those unexpected alliances?

While you could point to the Lobbying Act campaign that brought together PETA and the Countryside Alliance to collectively voice the concerns they had about the space to campaigner, on the whole have we have become to timid in the unexpected alliances that we’re building.

Make Poverty History might have forged a unusual coalition of development organisations, faith groups, trade unions and many other which got noticed inside Downing Street, but do campaigners today too quickly default to the ‘comfortable’ alliances which while broad have ceased to be ‘unexpected’ by decision makes.

Perhaps it’s because unusual alliances are harder to form in a social media age, when the backlash from an organisations or individuals ‘base’ is much easier to amply and quantify. Forsyth’s advice on that was that charity leaders shouldn’t be scared by criticism of unusual alliances – but rather asked to be judge on the impact they have.

So how do we start to build those really unexpected alliances?

1 – Think outside of the box – Stonewall is a cracking example here, partnering with Paddy Power to raise awareness of homophobia in Football, knowing that working with the firm would help them reach new audiences that Stonewall wouldn’t have alone.

2 – Prepare to be judged on impact – Justin’s advice is right, albeit hard to hold onto when your the organisation or individual being criticised, but unexpected alliances are those that make the political calculations that they’ll have the influence that’s needed at the highest level.

3 – Become a bridge builder – As Lisa Witter writes in this excellent article ‘leaders seeking to make social change are like all people: They feel most comfortable associating with others who share their point of view, values, and priorities’ but instead challenges us to become bridge builders ‘people and organizations that draw their power from their connections across issues and sectors, and specialize in translating the language of a specific issue tribe for (and building relationships with) potential allies outside of it’.

Her tips for doing that well are;

- Have the right expertise to know enough about an issue but not too much knowledge.

- Ensure others trust you.

- Work towards a cause, not a brand – this mirrors the point that Forsyth made about the need to build powerful platforms not just organisations

- Be connected

- Be a skilled communicator – to attract people and make them feel heard.