Last week, I joined 30,000 others in Liverpool for Labour Party Conference – I was attending in my role at Save the Children UK.

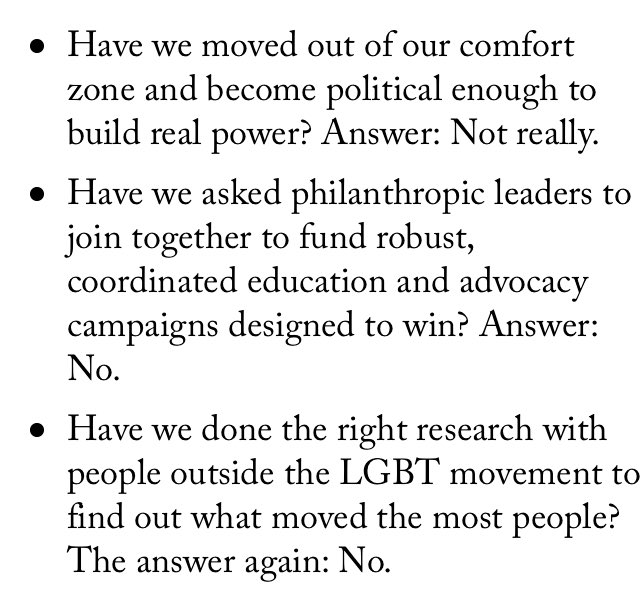

I’ll not add to the hot-takes because you can’t seem to avoid LinkedIn for them, but as someone with a background in campaigning it was interesting to think about how to most effectively use ‘outsider’ tactics at a political conference which is often viewed as a peak ‘insider’ influencing moment.

Conference is a really controlled space centered around the Secure Zone where most of the fringe events and main conference hall is. You can only get in with a pass.

Understandably there are lots of staff from the Labour Party and others making sure the event runs as planned. That’s fair enough it’s their conference and they want to do what they can make sure it follows the aims and objectives they have for it. But it really limits what you can do as a campaigner inside the conference.

For example on one of my ways through security I had to show them what was on a rolled-up poster I’d bought about joining a union inside the conference (by the way you should also join a Union). There are ways to get campaign messages visible but it’s often about getting it on lanyards, badges, t-shirts, etc.

Most key ministers and advisers stay in the Secure Zone for the whole conference – it’s a real bubble, so lots of things that happen outside just don’t get noticed so it’s helpful to be realistic about what can be achieved.

You spend most of your day getting between venues for fringe meetings, 1:1 conversations, receptions, and other events – to get into the Secure Zone you generally had to walk past a range of different protests who were happening just outside.

They came on all issues – from pro-EU campaigners with a very loud sound system and flags, to protest on Gaza, plus a range of other issues – although to be honest it wasn’t always easy to work out what the campaign was on in the moments you had as you walked in.

If you’re going to protest outside the entrance – make sure it’s really clear what your message is, and try to make how you amplify it different from everyone else.

You also find as you go into the venue you’ll get handed flyers for a whole range of topics – some are campaigns trying to influence the internal votes/motions that are being debated by Labour members, others are for fringe events, and others are on a range of concerns – I’ll be honest I can only remember a few of the flyers as they often contained lots of information in them.

The most effective campaign outside the entrance was from the NEU (more on them below) where on one morning they had a whole class of school children encouraging us to sign a petition on free school meals – it worked as it was different, the children wanted to talk with you, and they had an action you could take.

I saw loads of campaigns using ad vans across the week – I tried to do a little thread of them over on BlueSky. I noticed them, and others must do as well as I had a couple of people mention they’d seen some vans that Save the Children had hired on the two-child limit on Sunday.

I don’t think billboards worked well at this conference – but that’s probably a result of the fact that the Waterfront in Liverpool is beautiful and doesn’t have any billboard sites. I saw some further away in the city center so you would only see if you were getting the train/bus into the city or walking back to a hotel – but that might be different at other cities like Manchester or Birmingham where there are more spaces close to the venue.

I didn’t see any projections in person – but I know 38 Degrees and others did a some around the city.

The most effective campaign during the week was from the NEU on Free School Meals because it was so joined up – they had ad vans, the school children outside, their stall in the exhibition area, delegates with sticker, and their conference fringe events were linked to the issue. You couldn’t miss it. And that projected into their digital campaigning as well during the week. It was an excellent approach.

The Daily Mirror did the best campaigning panels – the highlight of my fringe was an event with these young people, that in part as they able to bring the campaigning brand the paper has with it’s political contacts to get those with power to listen to those who have been involved in their campaigns.

There are definitely opportunities here for campaigning organisation to do more with fringe events – for example thinking creatively about who’s invited to be on a panel, but the risk is that lots of work can go into planning an event only for your key political target to pull out.

It’s important to remember that alongside the fringe events and networking is a political conference happening – that includes Labour members voting on and discussing motions on a range of issues. It’s a complicated process to use – but Unite used it effectively to get conference to vote against cuts to the Winter Fuel Allowance.

Everyone spends lots of time on their phones at conference – everything is arranged via WhatsApp, and most people seem to following what’s happening on Twitter/X. I think there are tactics/approaches which could get campaigning content shared and spread that way – perhaps paying for geolocated adverts, or trying to seed content that’s shared via WhatsApp. Something to think about.