In the last few weeks many of those I work and campaign alongside have joined the Labour Party. So for readers who aren’t members of the Labour Party (or interested in party politics), please forgive me as I go ‘off topic’.

For those who have joined. Welcome.

I’m glad to be on the same team as you. I hope these notes will be of use, because I was like you just 7 years ago and have had the most amazing time being involved over the last few years. Like you want to see a Labour Government in 2020 because I believe we achieve more in power in one day than we do in a 100 days in opposition.

1 – Remember we are one party – You won’t agree with everything that everybody says all the time, and not everyone voted for Jeremy Corbyn (I didn’t but that doesn’t meant we can’t be friends!). But 99% of people I’ve met within the Party are members for the right reasons (and many of them are still exhausted from an General Election campaign followed by the Leadership election). Like you they have a passion for social justice and a fairer world. More unites us than divides us. So look for the good in everyone you meet.

2 – Get involved now – Don’t leave it until 2019. The media are looking for a story about how Labour is unelectable and the 2016 elections in London, Scotland and in councils across the country will be the first time they get to write that story. It’s easy to join interest groups within the Labour Party, known as Socialist Societies. They can be great ways to meet people who share your interest, but please get involved in your local Constituency Labour Party (CLP) as well.

Bring your skills, energy and experience as a campaigner and get stuck in. I can’t promise that it’ll always be easy, but CLPs are the basic organising unit for Labour and they need people like you in them. It’ll also help you get to know your community, its only through my involvement in Tooting Labour that I’ve had the pleasure to make friends from across my community.

3 – Knock on some doors – Firstly it’ll make you a better campaigner, but it’s also the most effective way we have as a party of getting out . The person who’s taught me the most in the Labour Party has a phrase that is so true ‘friends do things for friends’ and talking to people all year round is a way of doing this.

Sure we need to change the way we run our canvassing, engage in more of a conversations, find ways of empowering local people to take action so we’re doing it with people rather than for them, but disappearing from our communities won’t help people think that the Labour Party is a ‘friend’.

4 – Find the people who inspire you – Some of the people you’re going to meet in your local party aren’t going to be the people you’ll want to bound down to the pub with, but at meetings and events you’re bound to spot people who interest (and perhaps even inspire) you.

Get to know them, as my guess is that they’re the type of person who’ll want to change things, but perhaps because they’re now a Councillor or a CLP Officer they don’t have the time or energy to do that (I remember bounding into my local party in 2010 full of ideas but if I’m honest by 2015 I’d run out of some of that energy to get things done as the pressures of life and helping keeping my local party going got to me). Get to know them, ask them how you can help to change the culture of your CLP, make plans, share ideas, work together. These people want to pass the baton onto you.

5 – Stand for office – Within the next 12 months each CLP will hold elections for its officers – the volunteers who make things happen. Consider standing for office to bring your skills and ideas to help run your local party. If you want to really change things this can be a great place to do it, and if you are successful get to know others in the same position in other constituencies to share ideas.

6 – Change the ways meetings happen – There are some cliches about parts of Labour Party meetings which are fair, but you can help to change the way meetings are held.

Suggest changes to the venue to make it more welcoming, think about the set up – do you have to sit in rows, change the agenda – we used to have the speaker/policy discussion first followed by the business later – it’s amazing how many people don’t complain about the minutes of the last meeting when they want to get home at 9.30pm! Ensure that you find ways for more people, find speakers who’ll be interesting, helping to facilitate discussions in small groups, etc, etc.

Every time you walk away from a meeting because you found it dull those who are happy with the status quo win! Don’t just complain, go with suggestions to change things.

7 – Help outside of London – Historically local parties in London and a few other large cities have been much bigger than in many other areas of the country, so if you’re interested in helping the party win in 2016, go on a road trip to help the party in those marginal seats in the Midlands, Kent, and beyond we need to win in 2020 to form a government.

8 – Believe we can win everywhere – I grew up in Surrey Heath, its an area unlikely to elect a Labour MP anytime soon, but there is a ward that does have 2 Labour Councillors. If you’re in a safe Conservative seat ask around to understand if there are similar wards we used to be active in, and if there are think about getting involved. In the 1990s, the party ran a brilliant programme called ‘Operation Toehold’ which helped the party to start winning in seats that they eventually took in 1997. We need the same now, to show that Labour can win up and down the country.

9 – Get to know your organiser – As my local MP never tires of reminding our meetings, we’re a volunteer party, we don’t have lots of paid campaigners, and most Councillors and Officer do this alongside the ‘day job’, but many CLPs do employee an organiser. They’re often brilliant young campaigners, who are asked to work miracles week-in, week-out for little pay. Get to know your organiser, offer to share your campaigning advice, encourage them, and ask how you can help.

10 – Always have some loose change in your pocket – You’ll soon find that the Labour Party loves a good raffle. It’s because most local parties don’t have huge reserves, so every opportunity to raise a few pounds will help to fund the next newsletter or the organisers salary.

PS – Get in touch if I can help offer any advice. Together we’ll win again.

How campaigners can help ensure crisis equals opportunity..

It’s an appropriate question given the headlines on the current refugee crisis, and the opportunities for advocacy and influence that it appears to be providing for many groups who’ve toiled on these critical issues for years.

So how do we, as campaigners prepare for those crisis, that cause a set of fundamental assumptions or rules to be challenge in such dramatic way.

It’s all to easy to see crisis as something to be avoided, but as this excellent article on the missed opportunities for progressives from the 2008 financial crisis suggests ‘crisis equals opportunity, for those who are ready to use it’.

1. Take time to prepare – We can’t anticipate every crisis, but how much time do we spend preparing what we might do.? Look around at those who’s job it is to respond to unexpected crisis, from the security forces, who play our scenarios often on a grand scale, to the staff in the humanitarian response departments of many large NGOs. They role play. It means in the unlikely event of those situations happening they know how to react most effectively.

Can campaigners learn a thing from this? One of the things I enjoy most about Campaign Bootcamp that I helped to set up is the way we use a scenario to bring the campaigning that we’re teaching too life. I’m struck by how little we actual play out how we’d respond to different scenarios. How many team away days are dedicated to exploring what we’d do if.

2. Have a set of asks on the shelf – The father of free market economics, Milton Freedman is often quoted ‘When that crisis occurs, the actions that are taken depend on the ideas that are lying around. That, I believe, is our basic function: to develop alternatives to existing policies, to keep them alive and available until the politically impossible becomes the politically inevitable’ so campaigners for change’.

Do we have the same for the issues that we’re campaigning on? It doesn’t need to be long document, but something that could be dusted down. It might be seen as an indulgence, but I’m struck how the 2008 financial crisis came and many of those working on economic issue didn’t have a set of responses ready to go. There were opportunities to push for significant change but we didn’t have those asks to hand..

3. Look for the signs – Predicting crisis isn’t easy but taking time to learn the skills of those who effectively predict what might happen is a useful skill to add to a campaigners toolkit. What is that they were looking out for that helped, what was the evidence that they saw that led them to a different conclusion to the mainstream?

In the Pathways to Change: 10 Theories to Inform Advocacy and Policy Change Efforts, the authors talk about the ‘Large Leaps’ theory of change, suggesting that change can happen in sudden, large bursts that represent a significant departure from the past. The theory holds that conditions for large-scale change are ripe when the following occur:

As campaigners are we looking out for those signs?

4. Hold your nerve, but don’t cry wolf – There’s a risk that anyone who focuses on looking for a crisis can cry wolf. Spotting what they perceive to be a crisis, but isn’t actually one. Do this too often and your credibility can take a hit. The skill for any campaigner is to hold steady, seeking the evidence that the crisis is real and calling out the opportunities. One of the things that we’re going to be discussing with Tearfund colleagues is the difference between the opportunities presented by the climate and financial crisis. Perhaps the different here is the climate crises feels like its a long-term challenge, while the financial crisis was a much more sudden shock that we didn’t anticipate.

5. Present a positive vision – Crisis are unsettling, things we thought in the past were true are no longer, and at that moment its easy for campaigners to revert to the ‘told you so’ high ground, but as George Lakey suggests “when crisis comes, who is ready with what vision?”. In this article he argues that the both Occupy and 1968 French Student protest failed in part because they didn’t have positive vision that gripped the mainstream. He suggests that ‘in addition to campaigning, I would add another building block: Try empowering the visionaries you know to do homework. We’ll need their vision work — in concert with wide discussion — for the next crisis’.

How To – Handover a petition to Downing Street

In hope it’s helpful to others. Here are my top tips;

- The security for Downing Street is overseen by Charing Cross Police Station so you’ll need to give them a call about booking a slot. Make sure you give as much notice as you can. I’m not clear on how many slots there are per day, but there are some times when you shouldn’t expect a slot, when Cabinet is meeting for example.

- You’ll need to fill in a form which provides the details of everyone who’ll be going up to those famous doors. Your allowed to take 6 people and unless your photographer is a member of the NUJ (National Union of Journalists) they count as part of the 6.

- On the day you’ll need everyone coming to bring along appropriate ID. MPs and members of the media who are members of the NUJ don’t count as part of the total.

- You can’t take in props or fancy dress and you’ll probably be limited to a box of petitions (about the size that a ream of paper comes in). The best hand-ins that I’ve seen normally have someone holding a sign which explains the campaign and the number of actions plus a well branded box. Organisational T-Shirts are fine. If you Google Image Search ‘Downing Street Petition’ you’ll get a good idea what’s possible.

- When you arrive, go the security gate on the left of Downing Street, expect to go through airport style security (so perhaps have someone waiting outside with bags and other belongings) and then your given an appropriate amount of time to walk up the Street and to the Door.

- Don’t expect to be able to linger too long- you’ll get 30 minutes maximum. Most of the time the street is quiet but if your lucky you might find a few journalists and camera crews waiting in the pen across the street you seen them talking from on the news.

- As with any good campaign, plan what photos and footage you want to get before you go in. Think about how you want your photo to look like. If you want to get any short pieces to camera for filming expect to do that by the media pen you see on TV.

- The Prime Minister doesn’t come out to collect your petition, but you do get the opportunity to knock on the door and handover the box of petitions to the police officer.

- Remember the front door to No 10 is the door to an office, so staff will be coming in and out while you’re on the street. They could be important so make a good impression!

- I’d always make sure that at the top of your box is a letter which has your campaign asks in it and the number on people who’ve taken action. You probably want to get your public affairs colleagues to email a copy of that to your relevant Number 10 contact – don’t suppose they’ll hear about it because you were outside the building!

- If you’ve got loads of boxes of petitions then the rest need to be taken to a Post Office near Victoria Station – exact details are on the form you’ll fill in. I’ve no idea what happens with them after that, although sadly I don’t think they end up at Number 10.

- Your going to get loads of footage and images from your handover. They’re great for feeding back to supporters who took action and on social media.

These are my notes based on my experiences over the years. Things change so please do share any updates you have in the comments below and always check with the relevant authorities before you start planning.

Here's "cow" you do it. Learning from #MilkPrice campaign

There British brethren haven’t been as visible, but over the last few weeks the success of dairy farmers in getting supermarkets to increase the price the pay for milk has been a summer campaign success, and from what I can tell all without the need for an email petition.

It’s been an interesting campaign to follow and I’ve been struck by a few lessons for all campaigners from it.

1 – Pick the right target – the farmers haven’t focused on all supermarkets but a handful (Morrissons and Asda) that aren’t paying a fair price. It’s a smart approach focusing on brands that are in a very competitive market and don’t want to be seen to lose the favour of customers. By playing the supermarkets off against each other they’ve created a virtuous cycle where no retailer wants to be caught out. Interesting now they’ve won the first round, all the supermarkets have agreed to pay more, the asks and target of the campaign aren’t nearly as clear but they’ve got the momentum of a quick win.

2. Think about the values behind your messages – listen to any of the protesting farmer and, yes there are messages about the importance of preserving our rural way of life and protecting our national food security, but it’s also about fairness and hard working farmers being bullied by the profit driven supermarkets. They’re powerful messages that will resonate with many whatever their political persuasion. It’s a smart communications strategy.

3. Produce a great image – Who can’t fail to find both the images of farmers buying up all the milk in a store with the #milktrolleychallenge or even better taking a cow into a supermarket an intriguing and powerful image. Firstly through social media and then through broadcast media it’s a great image to fill the media in the traditionally quiet ‘silly season’.

4. Find authentic spokespeople – I’ve actually no idea if any specific organisation is behind the campaign (I’m assuming it’s the NFU or similar) but that’s in part because everyone I’ve heard interviewed for the campaign is a farmer, so the message is direct from the (ahem) horses mouth. What the campaign has lost in professional polish it’s gained from an authentic and directly affected voice.

Lessons from the Field – my reflections on 5 years organising for the Labour Party

Last month I shared a few thoughts about what issue campaigner can learn from party political campaigning.

A few people encouraged me to do the opposite post, but as I started writing I discovered this isn’t really lessons for political parties from campaigning organisations, it’s more my reflections from 5 years as a volunteer campaign organiser within the Labour Party.

Some caveats to start with. My experience is perhaps an isolated one, I’ve been focused on working in support of one party in a few constituencies in SW London, and I can’t say that I’ve managed to address everything I’ve written in the constituency I was involved in, but they’re a few observations, which feel timely as the Labour Party considers its future direction.

I’ve tried to avoid too much of a focus on the idea that too many party members are focused on the minutes of the last meeting, that we send too many emails (which we do!) or we only visit at election time (which we don’t).

Why? Yes, it’s sometimes true we do all those thing but it’s also an unfair parody. Many of those I’ve worked alongside have been committed, dedicated individuals who put in hours of volunteer time determined to make a difference in their community. Instead I’ve chosen to reflect on the following.

1. Don’t forget to evaluate – I’ve been through a number of election campaigns now, they’re all different, but in all of them I’ve spotted things I’d do the same or do differently. It’s surprised me that the political parties don’t have a instinctive or systematic approach to sitting down, evaluating the evidence and learning what’s worked and what hasn’t.

Perhaps its because politics is always moving along, win and you’re into governing. Lose and the last thing you want to do is reflect on what you did wrong, but it’s a practice that needs to be encouraged at all levels of the party. Personally, despite feeling numb from the result of the election in May, I’m glad the Labour Party has committed to do a full review of what worked and didn’t work, and it’s great to see some of the candidates do the same. That needs to become the norm not the exception, and the findings need to be distributed widely.

2. Test, trial and try new – Elections are in many ways won (or lost) using the same formula that parties have been using for years. Yes, there are a few examples of doing differently (Birmingham Edgbaston is the example that was rightly praised in 2010 and Ilford North in 2015) but outside a few campaigns committed to pioneering , and the work of the Labour digital team who I think awesome, new approaches seem to be to too often few are far between and not mainstreamed quickly.

Innovation is hard when the risk of it not working is losing an election, and not all campaigning organisations get this right either. But I’d love to see the party embrace a culture of testing different approaches to see what has the biggest impact, trailing something new, building an evidence base based on experimentation.

It doesn’t mean throwing the old playbook out (there is much to be said for the approach of going door to door and being routed in a community) but the playbook needs to have some (evidence-based) chapters added to it.The experience of Arnie Graf and the suspicion with which his community organising approach was viewed is a lesson in how hard this can be.

3. Share learning – In the overall scheme of things I was a fairly unimportant volunteer. But with a (unhealthy) passion for campaigning that took me to the US to learn how Obama did it in 2012, I was amazed at how little learning and good practice is proactively shared amongst other volunteer campaign organisers. I’m sure there is loads I could learn from others across the UK, but I found more ideas from reading books and blogs about what was happening in the US than I did others in the UK.

The Labour Party would do well to emulate a model similar to that of the Analyst Institute in the US and build a closed community committed to share evidence and best practice for paid staff and key volunteers (like me). But learning shouldn’t be limited from within the Party, since the election its been more interesting reading learning from Conservative activists, like any good campaign the party needs to be open to collecting ideas for a range of sources.

4. Remember the pyramid of engagement – A graph like the one below should go up in every Labour Party office. Sure some really skilled professional people just love to deliver leaflets (I’m one of them now – it’s good exercise) but too often that’s all we ask them to do, just knock on doors or deliver leaflets.

The pyramid of engagement is a tool well know to campaigners, all about how you help you develop a plan to recruit individuals and engage individuals. Some constituencies do this really well, but sadly most don’t meaning talent is wasted or under-utilised.

5. Invest in your people – The Labour Party relies on a small army of organisers in many of its constituencies, most are recent graduates paid too little, and asked to make huge sacrifices of time in the run up to an election. Some are stick around for year, but most drift away after an election or two. That’s valuable institutional knowledge walking, and a huge cost in training new staff.

We don’t have the culture in the UK of a professionalised political campaign staff, but as a result there a few incentives for the most effective organisers to stick around, the training they get seems to be patchy and the support/supervision from more experienced staff limited. Building a clear career pathway that rewards the most effective rather than those who have the most stamina, and effectively scales to provide the right level of support and supervision is needed if we’re to build a cadre of brilliant campaign managers.

6. Build a culture of accountability – At times, asking how another constituency how many contacts it’s made is similar to asking someone else how much they get paid. It’s shared with reluctance and is probably over or under inflated! Work needs to be done to ensure the metrics are more sophisticated than simply the number of contact made, although that’s still an important benchmark of activity, to ensure they’re capturing volunteer engagement and much more.

But those figures need to be shared and scrutinised. To my mind it’s unacceptable that we don’t have a culture where one constituency can benchmark itself against another and those who aren’t performing, including where we have longstanding MPs, are called out by the National Executive Committee or another representative body.

So a few lessons from me. As I was writing this I re-read parts of Refounding Labour. It’s a document full of practical recommendations. It would be easy for whomever becomes leader in September to bin it, as a holdover from the previous leadership, in my opinion that would be a mistake.

Get my latest posts sent directly to your inbox – sign up here.

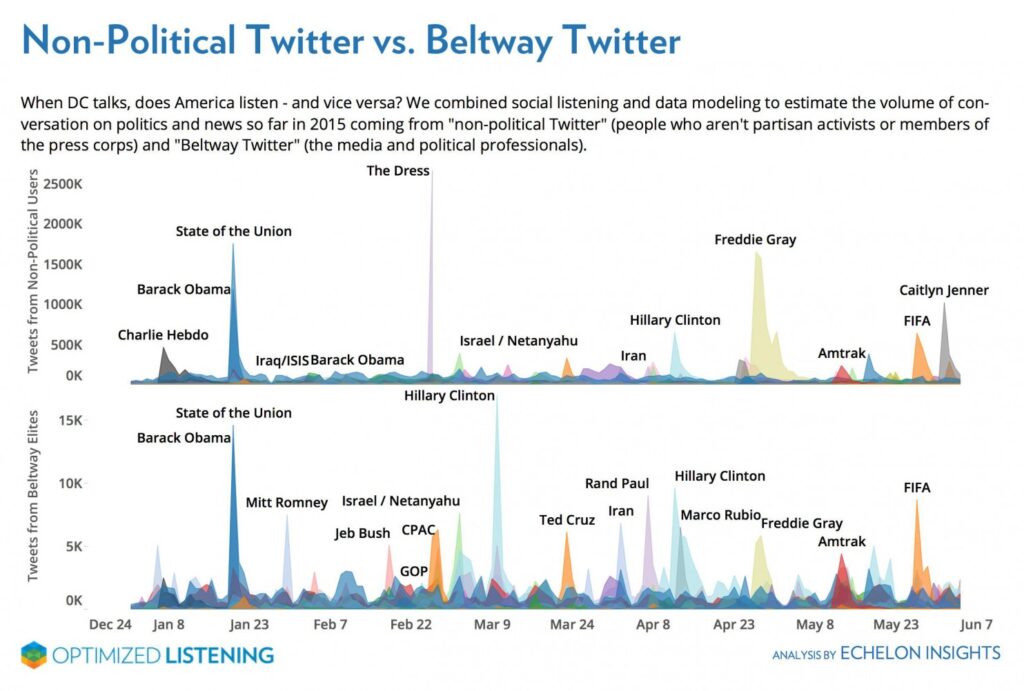

Beware the Twitter echo chamber – Graph of the Week

One Direction (don’t pretend you don’t know who they are!) supported the Action/2015 campaign a few weeks ago. The engagement on Twitter was amazing, I’ve never seen so many RTs so quickly but you didn’t see any of that action on my Twitter feed (follow me at @MrTomBaker).

That experience and this article on the role of social media in people thinking that Labour would win the election got me thinking about how Twitter is a big echo chamber with lots of political people talking to each other but often few campaign cutting through beyond that.

I’ve not seen any similar research from this side of the Atlantic, but this graphic, which looks at what those inside D.C. Beltways (the US equivalent of the Westminster bubble) posts on Twitter versus what everybody else in the US posts on Twitter is instructive.

Five for Friday – Winning the support needed

I’ve been thinking a lot over the last few weeks about the importance of starting with the audiences you need to win, rather than the activists we already have.

So this Five For Friday is a collection of articles that have helped my thinking in the last few weeks;

1 – Kirsty McNeill on the difference between ‘people power’ and ‘activist power’ and the importance of understanding that difference.

2 – How the Equal Marriage campaigners in the US realised they needed to change the framing of the message (and the 10 lessons from the campaign)

3 – I’ve shared this before, but Roger Harding on how Shelter moved housing up the agenda is a must read for all campaigners.

4 – 10 years on from Make Poverty History, here are some reflections from the lessons of a campaign that got 90% brand recognition from Kirsty (again!) and my colleague Alice Delemare.

5 – More insight from how the Conservatives did this so well in the last election by ruthlessly focus on the people who matter.

10 years later – some personal reflections on Make Poverty History

2005 was a good year, I got engaged, England finally beat the Aussies to win the Ashes, and I got to work on the Make Poverty History campaign.

Make Poverty History was the first big campaign that I’d be paid to work on. It was a huge movement that mobilised 100,000s of people to take action on debt, aid and trade as the UK government hosted both the G7 and the EU Presidency.

This week, its a decade since the biggest moment of the campaign, a huge 250,000 person march in the centre of Edinburgh, accompanied by the Live 8 concerts on the eve of G7 leaders meeting in Scotland.

10 years later, and it’s still the campaign that I mention when I try to explain what I do to my second aunt.

While lots has been written about the impact of the campaign, being the first campaign that I was really involved in organising I’ve been reflecting on the campaigning lessons that Make Poverty History taught me. There are lessons that still apply today;

1. Unusual coalitions deliver change – at the time, I remember a friend who worked in a totally unrelated job at Number 10 talking about how the unexpected partnerships around the table the campaign was creating waves internally. Bringing together 500+ organisations meant that the campaign couldn’t be dismissed as just ‘the usual suspects’.

2. Be prepared for the second act – I’ve written about this before, but the campaign ran for the whole of 2005, concluding in a Mass Lobby of Parliament in the rain on trade justice in November, but because the majority of the resources had been deployed to ensure the push towards the G7 moment was as successful as it needed to be, the campaign didn’t have the resources for the ‘second act’ causing a loss in momentum over the summer, and the impression by some that the campaign had come to an end.

3. Sometimes you need to let it go – I remember that it quickly became apparent that the campaign had captured the public imagination, individuals were calling up with , events being organised across the country, churches want to wrap their spire in WhiteBands (the symbol of the campaign) and much more.

Now we’ve become very used to the idea of more decentralised ‘bottom up’ campaigning, an approach pursued by groups like 38 Degrees, but at the time it was uncomfortable for organisations who’d been used to a more ‘command and control’ approach to managing their campaigns. If our campaigns are to come to life we have to be prepared to let the brand run a little wider than we’d immediately feel comfortable.

4. A good campaign has a halo effect on its targets – most of the MPs who were lobbied as part of the campaign probably can’t remember the details of the policy asks from the time, but the impact of the campaign have lasted well beyond 2005. Long after the campaign has come to an end politicians who were lobbied still mention Make Poverty History. As we get further away from 2005, that effect is definitely declining, but even today I think we’re getting wins on international development issues as a result of the campaign.

5. A campaign can benefit from a ‘radical flank’ – the tensions within the campaign, between organisations who had different political and policy analysis have been written about elsewhere, but the campaign was a excellent examples of the concept of the ‘radical flank’ when the positive or negative effects that radical activists for a cause have on more moderate activists for the same cause. Did those groups who took more ‘radical’ position help mean that the asks of the campaign were seen as more ‘moderate’ by the government and thus achieved?

6. The transaction costs of building coalitions are high – Make Poverty History was over a year in the making before it was launched in early 2005, it took many hours of meetings and discussions to reach agreement, a reminder that the start-up costs of forming coalitions are often significant. This work was helped by a tradition of working together that had come from previous campaigns on debt and trade by many of the key organisations, the need to keep this type of infrastructure in place is vital to build trust and bring individuals and organisations together.

7. Building public support is really hard – Make Poverty History had a brand recognition of 90%, but despite all the high profile media, celebrity involvement and grassroots chatter, the evidence suggests that it didn’t lead to a significant increase in the number of people ‘very concerned’ about global poverty issues. It’s a reminder that building public support requires sustained attention (and perhaps using the right frames).

8. Don’t be afraid to try something new – The campaign adopted this approach ‘“don’t be afraid to be the first to ‘crack’ a new platform, give trendy a try, and take a risk!”. In many ways Make Poverty History was the first internet campaign, albeit one with a campaign video where you had to select the speed of your dial up connection, comfortable trying out new approaches as we sought to understand the power of the web for campaigning.

Looking back, I’m incredibly proud of the small role I played in the Make Poverty History campaign, it wasn’t a perfect campaign (here is a secret – no campaign is) but one that taught me so much but more importantly delivered real results.

I’ll take the memories of Vicars walking to Downing Street, Nelson Mandela in Trafalgar Square, getting sunburnt in Edinburgh, staying up all night on Whitehall, and getting very wet outside Parliament wherever I go in my campaigning career. It was a very special year.

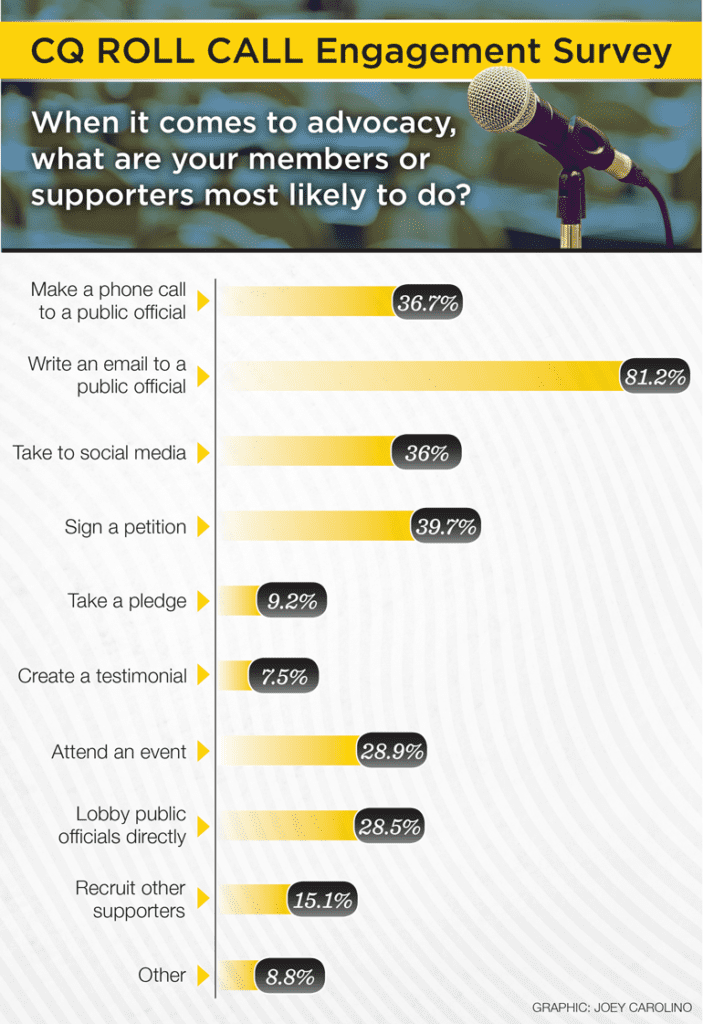

What advocacy actions are your supporters most likely to take? Graph of the Week

An occasional series of fortnightly posts with useful graphs for campaigners.

Spotted this in the very useful Connectivity blog. It’s from the US, but I suspect the results would be similar in the UK.

The findings came out at the same time as the results of the annual Benchmarks survey, which pulls in insight from 84 advocacy organisations, and found that;

- More people are opening advocacy emails. Advocacy open rates in 2014 were 16% — that’s 9% higher than the same organisations saw in 2013.

- Fewer people are taking action. For every 1,000 advocacy emails an organization sent, they generated 29 actions (we’re talking basic fill-out-a-form stuff like petitions and letters to Congress). That’s down 18% from the same organisations’ response rates in 2013.

Some useful food for thought as we consider who we get supporters to take the most effective actions to take.

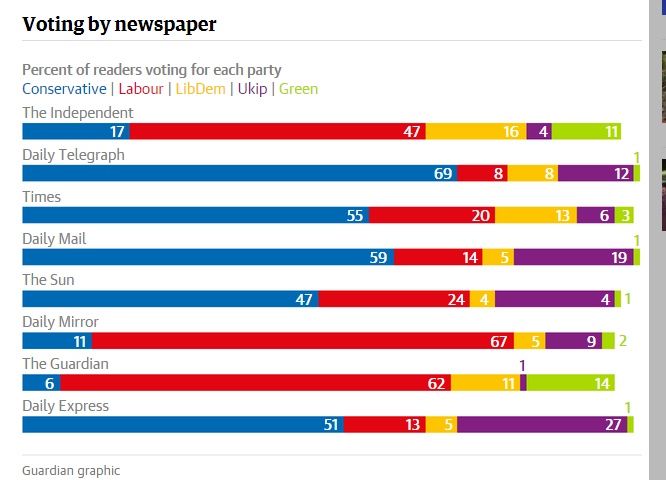

Which newspapers really matter for campaigning – Graph of the Week

The first in an occasional series of fortnightly posts with useful graphs for campaigners.

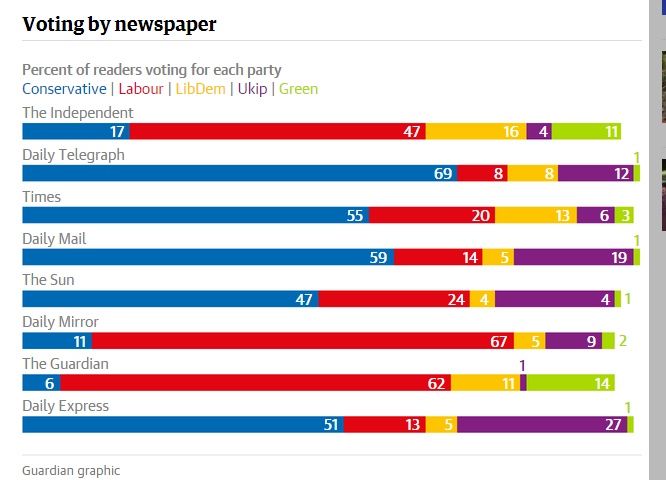

Campaigners spend lots of time looking to get media coverage for their issue. This graph is a good reminder of the political allegiances of the readers of each paper, providing useful insight into which papers are most important for the political parties.

It also broadly matches the parties they endorsed at the last election – the UKIP backing Express, and Conservative backing Independent are the only papers that backed a party different from the majority of its readership.

So if you want the Conservative government to back your campaign it can help to get coverage in The Sun rather than the Mirror, the Times rather than the Independent.

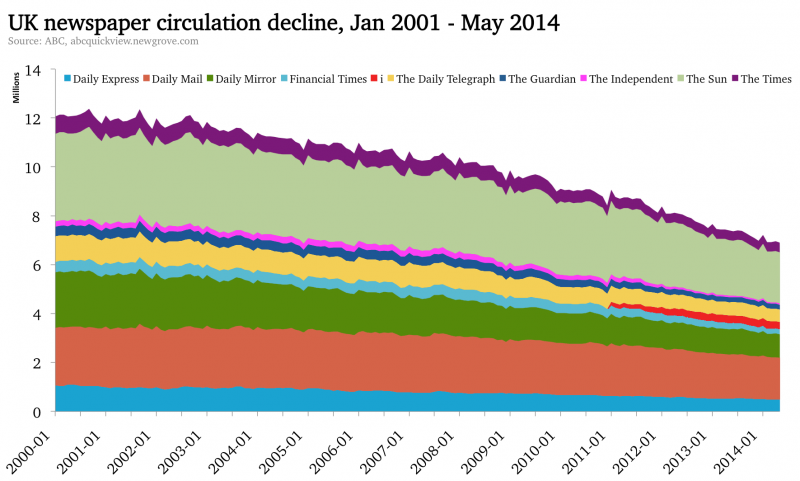

It useful to also to be viewed in conjunction with this graph, which shows the decline in readership,

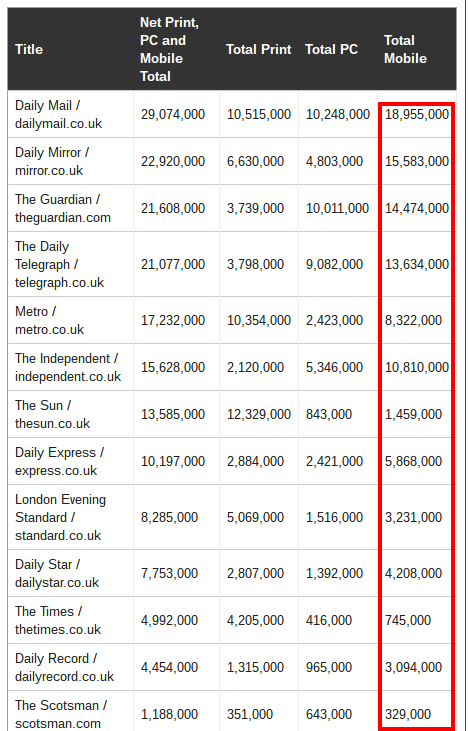

This table which shows the readership changes when you take into account the online and mobile readership.

Either way, given its the papers that it suggests if we want to be setting the agenda with our government then as as campaigners we should spend more time reading The Sun, Daily Mail or Telegraph, and less time with the more familiar Guardian.