A colleague in some recent handover notes wrote ‘while we talk a good game on organizing, we’re still really focused on mobilising’, or something to that effect. It’s a very fair challenge and one that I’ve been reflecting on since reading it.

Like many in the campaigning sector, I’ve got really excited about the opportunities that an organising approach to campaigning brings – not least because I’ve been inspired by the campaigns that are using it and winning, but the day to day model of campaigning that I’m most accustomed to is a mobilising one, and getting from one approach to another isn’t easy.

So I was really excited to get a copy of Matt Price’s new book ‘Engagement Organizing – The Old and New Science of Winning Campaigns‘ at the start of the month. I’d met Matt at the MobLab Campaign Con in Spain last autumn, and read some of his online articles looking at campaigning approaches in Canada.

Matt is based in Vancouver, so the case studies are drawn from NGO, Union and Party Political campaigns that are north of the 49th parallel. We might look across the Atlantic to the US for most of our inspiration, but the reality is that the similarities in political systems in Canada mean we’ve probably got as much to learn for our campaigners, and it was really nice to read some case studies of campaigns and organisations I wasn’t so familiar with.

But what I really like about the book is that it’s a practical how-to guide, that looks to blend together how campaigners can draw on the best of the digital. Instead of trying to push a particular organising perspective, or suggest that everything can be won by smart digital campaigning, the book explores how to blend these approaches together for maximum impact.

Lots in Matt’s book resonates, especially the chapter on the Engagement Cycle, as opposed to the more traditional pyramid of engagement, and also the stories of the approach of Cesar Chavez and the United Farm Workers in using house meetings as an organising approach.

At the end of the book, Price offers some reflections and challenges that prevent NGOs from embracing this approach. They got me thinking back to the challenge from my colleague, and if they’re true in the campaigning that I’m doing;

1. The work is hard – Price writes about the challenge of ‘organizers entropy’ suggesting there isn’t always enough energy in the system to do useful work. That means that organisers need to keep bringing energy into a system, and that often a win can take energy away as those you’ve organised feel that their goal has been achieved. That resonated – moving to an organising approach means keeping moving away from the norm. It’s learning a new memory muscle, and that can be exhausting. As a campaigner, I need to keep bringing energy into the system, and to those pushing this work forward.

2. Resources – while the ‘snowflake model’ shows that you can build an approach at scale with volunteers, and digital tools have lowered the costs for campaigning, Price points out that even then organising at scale costs money. Something that can be especially challenging in organisation where you need to continue to demonstrate impact and value for money. Again this feels very relevant – how do I resource the slow but important work of taking an organising approach, when the mobilising approach can demonstrate ‘quick wins’.

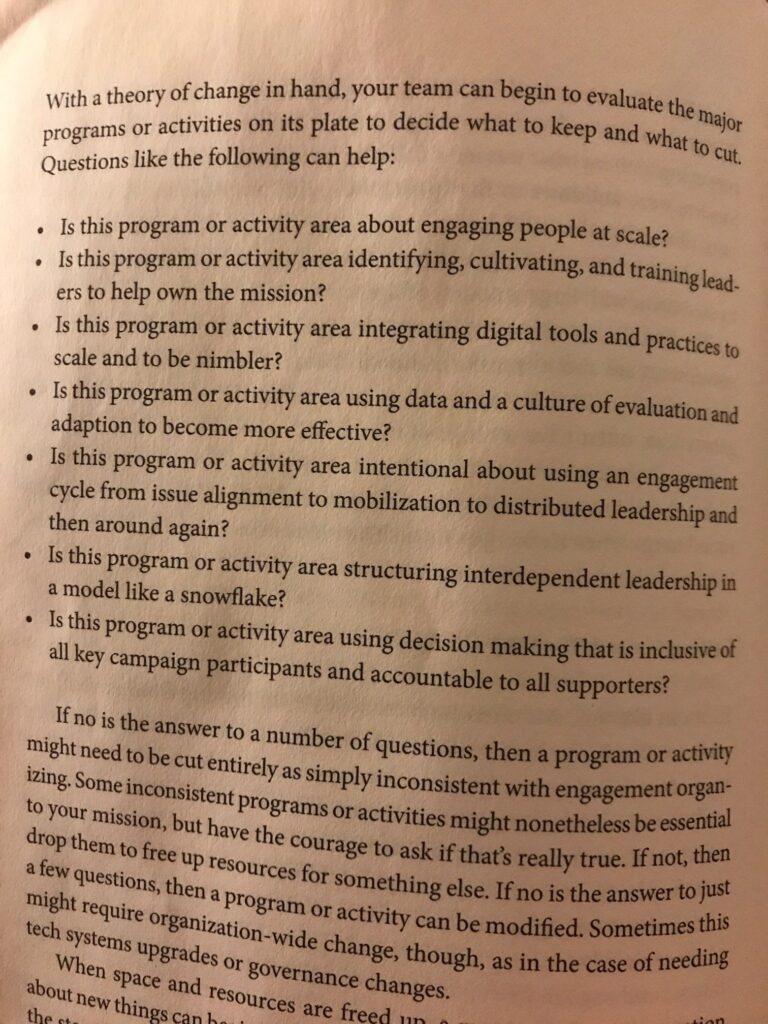

3. We don’t review our ‘stop doing’ lists – rather than a ‘to do’ list, Price suggests we need to ask some hard questions of what we’re already doing, and ask if they’re the most important things we can be doing to ensure we’re effectively using time and resources. It’s a really neat idea, and Price has some helpful questions to ask to help do it;

4. Overcoming organisational inertia – Linked to the work is hard, is the challenges we can face within our organisations with systems, practices, and cultures that are hard to change. Some of that comes from the experiences, practices, and expectations of those who’ve risen to more senior roles who’s campaigning was shaped in a more broadcast era (I count myself in this), some of it is about the systems we use which aren’t built, while culture is often seen as the ‘way we’ve always done things’ and is hard to shift. I’m not sure I have any simple solutions to this, but it’s something I’d like to reflect upon in future posts.

5. We need to talk about power – One of my reflections from time spent with Hahrie Han last year is that an organising approach requires us to have more conversations about power – its something that came through again reading the book. Both about how we give it away, alongside control to those we’re seeking to empower, but also how we ensure we’re directing our campaigns to focus on where the power is. As Han says ‘movements build power not by selling people products they already want but instead by transforming what people think is possible’.

I’d recommend Matt’s book for anyone interested in how to embrace a more organising approach in their campaigning.

Category: organisations

Speed, Sophistication, Structures and Space – 4 trends that will define the future of campaigning

In my role as Head of Campaigns and Engagement at Bond, I was ask to write about the trends that will impact the campaigning of members over the next 5 years, and what it means for our work to support members to campaign brilliantly. I came up with the following;

1 – Speed

The first campaign I was involved in was Jubilee 2000. I remember the record breaking petition, the sense of excitement as the latest Christian Aid News would come through the letterbox with an update, and the delighted when we heard we had succeeded in getting the G8 to cancel the unpayable debt.

It took the Jubilee 2000 campaign over 2 years to collect the 22 million signatures that formed the record breaking petition handed to G8 leaders. Anyone who collected those signatures will talk of the hours spent collecting petitions in churches, at street stalls and in student unions bars across the UK, winning the signatures one conversation at a time.

Fast forward to today, where it’s possible for a partnership between Guardian and Change.org to generate 250,000 signatures on FGM in 20 days, and many Bond members are able to generate tens of thousands of emails in a matter of days or weeks. Campaigning organisations able to launch a campaign in a matter of moments in respond to the latest event or news headline.

But while campaigning is getting faster, we’re also seeing a rise in slow activism? Organisations like the One Campaign and Tearfund are encouraging supporters to write handwritten letters to MPs around the recent legislation on 0.7% or All We Can encouraging supporters to stitch mini-protest banners ahead of London Fashion Week, part of creative ‘craftavist’ movement, which encourages reflective action that seeks to change the participant as much as it does the world. I think we need both within our movement, and a willingness to learn from both approaches.

2 – Sophistication

We know more about our supporters than we ever have, what actions the like to take, what topics they’re interested in, if and when they’ll open their emails from us, and as a result we can target our campaigns in more and more sophisticated ways. A recent report suggested “neuro-campaigning” following politics and advertising to use a better understanding of how our own brains work to persuade people to take action. With all this evidence, as campaigners we need to continue to invest more and more in testing of our messages and tactics before we share them.

A focus on what tactics to use, shouldn’t mean we overlook the importance of theories of change at the heart of our campaigning, including challenge ourselves to ask if we’re too focused on targeting our campaigning towards MPs, Government Ministers and UN bodies, or if we should follow Action Aid focusing on local councillors, or corporate divestment championed by Share Action and 350.org, or local media like RESULTS.

3 – Structures

As much as we need to build campaigning structures that are fit for a digital era, we shouldn’t overlook the importance of investing in an active and vibrant grassroots network. For me it’s always been the hallmark of our movement, the local activists that collect names on petitions and meet with their MPs.

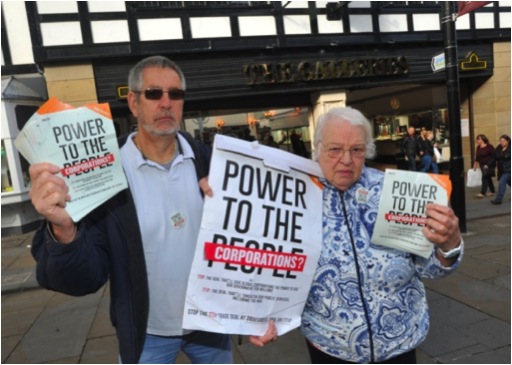

I want to learn from groups like 38 Degrees, about how they mobilised 10,000+ volunteers as part of the Days of Action on TTIP, or Toys will be Toys, an entirely volunteer led campaign about how they’re successfully joining up offline and online actions.

A focus on structures should not only be about how campaigns are organised, but also about challenging the very structures that perpetuate inequality and poverty. While we should take advantage of opportunities like the recent Private Members Bill on 0.7%, but the danger in focusing on ‘the little big thing’ is that we risk not building public understanding about the root causes of poverty that should be central to our campaigning.

4 – Space

The Lobbying Act or comments by the former Charities Minister that we should ‘stick to knitting’ reinforce to me that we’re seeing a narrowing of the political space campaigning organisations have to advocate. I believe we should feel proud as a sector of the positive impact our campaigning has had on the lives of the communities we work with. We should all fight to protect it.

Before starting at Bond, I helped to found Campaign Bootcamp, a training programme for those looking to start a career in campaigning. We were overwhelmed by the generosity and enthusiasm we found to help us. That experience has shown me the strength of the community we have, committed to work together to share and help each other.

This is an edited version of an article first published in The Networker available here.

While I've been away.

I’ve been in self-imposed blog exile for the last couple of months.

A combination of running a small part of an election campaign, two trips to the US for work, participation in an amazing action learning process hosted by the Common Cause team and a number of other commitments have meant that I haven’t been able to blog.

Here are a few things that caught my eye while I’ve been away;

1. Avaaz 2.0 – The global campaigning movement has launched a platform for its own members to develop and run their own actions. It’s still in beta mode at the moment but I’m sure that will change in the coming months. Also Change.org has launched its own UK platform with some great coverage. I’ve written before about how I really like the model that Change.org uses providing campaign organisers to help increase the impact of online petitions created by members. I hope that both will be successful.

1. Avaaz 2.0 – The global campaigning movement has launched a platform for its own members to develop and run their own actions. It’s still in beta mode at the moment but I’m sure that will change in the coming months. Also Change.org has launched its own UK platform with some great coverage. I’ve written before about how I really like the model that Change.org uses providing campaign organisers to help increase the impact of online petitions created by members. I hope that both will be successful.

2. Right Angle – The platform aims to be ‘a grassroots community. We exist to stand up for ordinary families – Britain’s silent majority’ and is supported by a number of Conservative MPs. So far, they’ve not had the same impact that 38 Degrees had in their first few month, although they were able to generate over 100,000 people to join their Facebook campaign against cutting fuel duty, so it’ll be interesting to see how the grow over the summer.

3. Twitter – It’s been great to see organisations engage with twitter in more and more innovative ways, two particularly impressed me. The Twobby of Parliament by members of the Care and Support Alliance, and the development of this tool by ONE which allows users to send messages to David Cameron on food security.

4. People’s Pledge – This sneaked under the radar , but I think the ability of an organisation to mobilise 14,000+ people in a constituency to vote for a local referendum on membership of the European Union is an impressive feat. With the introduction of the Localism bill, I wonder if we’re going to see more of this community level campaigning that leads to local ballots on issues.

4. People’s Pledge – This sneaked under the radar , but I think the ability of an organisation to mobilise 14,000+ people in a constituency to vote for a local referendum on membership of the European Union is an impressive feat. With the introduction of the Localism bill, I wonder if we’re going to see more of this community level campaigning that leads to local ballots on issues.

5. The next Make Poverty History – It was confirmed that development organisations are coming together to launch another ‘Make Poverty History’ style campaign in 2013. I’m sure this will be huge in the next 12 months, and I’m hoping that all those involved read this about lessons learnt and ensure that the next campaign is designed to avoid them.

6. KONY 2012 – I wrote before my blogging break about why the video had such a phenomenal response when it was first released, however the campaign wasn’t able to sustain the initial interest with the ‘Cover the Night’ event in late April failing to take off in the way they’d originally hoped.

7. US Election – Lots more great articles about different techniques and tools being employed in the campaign. I’d highly recommend every campaigner keeps an eye on the articles by Sasha Issenberg over at Slate, which I’ve found to be the most insightful into the approaches the campaigns are taking.

Life is returning to normality, so I plan to write some more on these topics and others in the coming weeks, as well as share the initial results I’m getting in government departments about the number of actions they’ve received in the last 12 months.

Why has Kony 2012 been so successful?

The Kony 2012 campaign is everywhere….if you haven’t heard about it you soon will!

Since releasing their latest campaign film just days ago it’s had millions of views (the statistics on the Vimeo dashboard show the way that views of the film have grown and grown since its release on Monday), been trending worldwide all day on Twitter and was filling up my Facebook wall last night, although many of these are comments which are rightly questioning the approach of the organisation and the campaign.

Since releasing their latest campaign film just days ago it’s had millions of views (the statistics on the Vimeo dashboard show the way that views of the film have grown and grown since its release on Monday), been trending worldwide all day on Twitter and was filling up my Facebook wall last night, although many of these are comments which are rightly questioning the approach of the organisation and the campaign.

In short, the campaign is about introducing the ‘world worst war criminal’ the leader of the Lord Resistance Army Joseph Kony, and calling for the US to provide troops to help arrest him in Uganda and bring him to trial at the International Criminal Court.

Both the message and organisation are proving controversial, as a development advocate I agree with many of the concerns about the approach the campaign has taken, not least as this blog describes it that ‘they take up rhetorical space that could be used to develop more intelligent advocacy’ that will lead to long-term peace in Northern Uganda and the portrayal of the solution as being delivered by an outsider alone.

But regardless, as a campaigner I also have to admire the effectiveness with which they’ve got out the message out in such a short period of time, and reflect on how I might be able to use similar approach to get what I hope to be more intelligent advocacy solutions. Here are my thoughts on why I think they’ve done so well.

1. Built and nurtured a community – I’ve not really been aware of the work of Invisible Children until today, but it seems that over the last few years they’ve been slowly building a huge online community on Facebook, with a million+ people ‘liking’ the campaign over the years as the result of showing previous films on campuses across the US, presumably much of the traction that the campaign has got is because many of these supporters have been sharing it. Cheap but effective mobilisation in action.

2. Demand the engagement of the viewer – There is a line at the very start of the film that says ‘the next 27 minutes are an experiment, but in order for it to work you have to pay attention’. At 29 minutes the film is very long and you’d expect to get board quickly, but the presentation is very engaging, well produced, fast-moving and doesn’t feel like it’s dragging at. It’s got many (all) of the elements of what a good campaign film should include, a story, a call to action and it’s emotive.

3. Communicated its theory of change clearly – It’s evident how the campaign thinks that change is going to come about and this is explained to the viewer. For them its all about demonstrating public support for action to a small group of political leaders, which interestingly doesn’t include President Obama. You may or may not agree with this approach but it’s simple and clearly communicated throughout the film.

I like the idea of influencing 20 ‘culturemakers’ who they identify as being able to spread awareness of the issues. I’ve not really seen this done in such a systematic way before, and it’ll be interesting to see how these ‘culturemakers’ will respond to the call in the coming days, presumably some of them have already indicated their support for the campaign.

4. Made it clear what they need you to do – The call to action at the end of the film is to do more than send a message to the selected targets, but it’s also an invitation be involved in making Kony known. The campaign is building on the knowledge that it’s an election year in the US and focusing on a night of action in April where supporters. It’s a bigger and bolder action, asking you to buy a kit full of posters and resource and make Kony know. It’s also again shows the high value that the campaign on individuals as multipliers of the message.

5. Put creativity and social action at the heart of the organisation – It’s interesting that the organisation isn’t one that was started by humanitarian professionals, but instead by filmmakers who were moved to respond on their first trip to Uganda back in 2003. They describe their mission as ‘using film, creativity and social action to end the use of child soldiers in Joseph Kony’s rebel war and restore LRA-affected communities in Central Africa to peace and prosperity’. You can see this approach is evident throughout the film, and it’s different to what you might expect from a more traditional NGO.

Thoughts? Comments? What have you learn’t from the success of the Kony 2012 campaign?

The US Presidential election and the future of campaigning?

It’s the US election season, and suddenly anyone who’s watched an episode or two of the West Wing will become an expert on the best approach to win the 270 Electoral College seats needed, the opportunities presented by the Michigan Primary and the role of Super Delegates in a tight convention.

While predicting the result of the Primary and Presidential race, and while we’re at it I think we’re going to see Santorum push Romney all the way to the convention and Obama will win a second term, is a great conversation starter amongst the political engaged, it’s also a good time to start paying attention if you want to see the future of campaigning.

Why?

Why?

1. The election campaign is has a bigger budget than any other. This year President Obama is expected to fundraise over $1 billion and I’d expect the eventual Republican frontrunner won’t be far behind, which means it can develop some of the most powerful tools and employ the best and brightest staff.

2. It’s the most ‘important’ single political campaign in the world to win. The President of the United States is still the world’s most powerful elected official.

3. It’s got huge numbers of people involved. The Obama team already has over 200 staff working full-time in its head office in Chicago, a figure that is likely to increase rapidly in the next month, plus hundreds of thousands of volunteers on the ground ready to be engaged and resourced.

While I accept that election campaigning is different to campaigning to change public policy, and that the campaigns will make use of many of more traditional techniques like TV adverts, that are perhaps less available to public policy campaigns. I believe it’s still interesting to see how the tools used in previous campaigns have often tracked closely to the tools that are now common place in most campaigning organisations.

As Slate notes;

1996 saw the debut of candidate Web pages

2000 was the first time website were used for fundraising.

2004 saw Howard Dean pioneer the use of online tools (like MeetUp) to organise campaign events to link supporters together.

2008 led by the inspiring Obama campaign saw the emergence of socia media as a mass-communication tool, and the most sophisticated use of sites like my.barackobama.com which turned online interest into offline activism.

Add to that the resurgence of the concept of Community Organising fueled in part by the background of the current President but also the way that it was put to work to increase registration and turnout of previous under represented groups. (If you’re interested in learning more about the 2008 campaign I’d highly recommend that you read ‘Race of a Lifetime’ and the ‘Audacity to Win‘.)

So what are the early trends for 2012? Well the overriding one seems to be the most sophisticated use of data.

Slate suggest;

‘From a technological perspective, the 2012 campaign will look to many voters much the same as 2008 did…..this year’s looming innovations in campaign mechanics will be imperceptible to the electorate, and the engineers at Obama’s Chicago headquarters racing to complete Narwhal in time for the fall election season may be at work at one of the most important. If successful, Narwhal would fuse the multiple identities of the engaged citizen—the online activist, the offline voter, the donor, the volunteer—into a single, unified political profile’.

While the Guardian reported this weekend;

‘At the core is a single beating heart – a unified computer database that gathers and refines information on millions of committed and potential Obama voters. The database will allow staff and volunteers at all levels of the campaign – from the top strategists answering directly to Obama’s campaign manager Jim Messina to the lowliest canvasser on the doorsteps of Ohio – to unlock knowledge about individual voters and use it to target personalised messages that they hope will mobilise voters where it counts most’

And this sophisticated use of data doesn’t seem to being the sole preserve of the Democratic Party, with Slate reporting in January about how Mitt Romney built a similar database to help him almost win the Iowa Caucus;

‘Romney’s previous Iowa campaign allowed him to stockpile voter data and develop sophisticated systems for interpreting it. It was that data and those interpretations that supported one of the riskiest strategic moves of the campaign thus far: Romney’s seemingly late decision to fight aggressively for his first-place finish in Iowa’

For more on the digital and data tactics that the campaigns are using take a look at this from the Washington Post and this from ABC News.

In the UK, we don’t have anything that comes close to the Presidential Elections. The nearest equivalent is the Mayor of London elections that are happening in May. It’s a highly personalised contest trying to reach one of the biggest single constituencies in the world, and certainly the Ken campaign is making use of some innovative tools;

1. Last week saw the launch of personalised Direct Mail which make of QR codes to invite a response.

1. Last week saw the launch of personalised Direct Mail which make of QR codes to invite a response.

2. The Ken campaign has made a significant investment in using Nation Builder tools to launch ‘Your Ken’ – a community to resource and mobilise its activists which was received with acclaim when it was launched last year.

3. The heavy emphasise on the use of text and email to get the message out to potential voters across London.

I’ll be watching with interesting at how both these elections campaigns make use of new tools and tactics in the coming months, and reflecting on the opportunities they present for campaigning for social change.

Learning from Stop the Pipeline campaign

The Stop the Keystone pipeline campaign is one that may have passed many in the UK by but in the US its resulted in a huge victory for environmental campaigners.

In brief, the campaign was looking to halt the construction of a pipeline that would transport tar sands oil from Alberta, Canada across the Midwest of the US to the Gulf of Mexico. You can read more about the pipeline here, and a few weeks ago President Obama announced that he wasn’t approving the go ahead of the pipeline.

It’s a real success for the campaign despite the fact that the campaign believes it was outspent by approx. $60m to $1m by the oil companies behind the pipeline, and research has shown that spokespeople for the pipeline were much more likely to be featured in the media. Although those involved are keen to point out that the fight isn’t over.

One of the most striking tactics that the campaign used was a fortnight of action in Washington DC where over 1,000 people were arrested for taking part in illegal sit-ins. Watching some of the films from August are incredibly inspiring and moving but in many ways these actions were the culmination of over 2+ years of campaigning.

[youtube http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ozmOQqRw0j4]

On Thursday, I joined a ‘Debrief’ organised the New Organizing Institute which featured speakers from a number of the organisations that had been involved in the campaign. It was a thought-provoking session, and I came away reflecting on the following lessons learnt from the campaign.

1 – The importance trusted leaders – One of the speakers, spoke about the importance of bringing Bill McKibben into the campaign. McKibben is the founder of 350.org and was one of the first to write about climate change for a general audience over 20 years ago. The speaker suggested that his involvement changed the dynamic of the campaign, as he was perceived by many as a trusted leader who brought credibility to the urgency of the campaign message.

It’s a reminder that as well as friends and family who remain the best ‘messengers’ for any issue, some authority sources can be incredibly powerful at mobilising a group of individuals. Who are these in our movements?

2 – They called for a bold action – Bill McKibben is clear that the arrests outside the White House was a key tool in moving the campaign from a local one in the states effected to a national one. The called for a bold action, for activists to do something very real and something powerful.

Social media was used to mobilise people to attend the sit-ins in Washington. Many of those who got arrested had not done so before, and the photos and visuals helped to define the issue – make it a visually compelling action, while running the event over two weeks helped to create a political drama that draws out the story, providing an ongoing story that reporters could focus on.

Watching the films from the fortnight you get an incredible sense of a community amongst those involved in the campaign.

3 – Building locally and ahead of time – Although the peak of the campaigns activities appears to have been in August, listening to speakers from both the Energy Action Coalition and Sierra Club, it’s clear that important work that was done over many years to build campaigning activities in local communities.

In the case of the Energy Action Coalition starting on campuses during the Bush administration, knowing that their would be a day when a group of trained and mobilised young people would be needed. While for the Sierra Club it was going to communities in Nebraska and other effected states, talking to people, sharing stories and mobilising them as part of the campaign, long before the attention was focused on Washington DC.

4 – Using political donors and volunteers – The campaign realised that they couldn’t counter the influence of the significant financial donations that the energy industry makes to elected officials in the US, but they could mobilise the tens of thousands of individuals who had made small donation to, and in many cases worked for the Obama campaign in 2008.

Using this tactics they were able to demonstrate the level of concerns amongst a critical ‘base’ that the president needs to re-engage ahead of the 2012 elections. Meetings at regional offices of ‘Organizing for America’, the Presidents election organisation, as part of a Obama Check Up Day also helped to demonstrate this. Although, we don’t have a similar culture of politician donations in the UK, I can still see opportunities in approaching an issue in this way.

5 – Collaboration and coalition – This wasn’t simply an outsider campaign strategy, the coalition was an especially broad one, with insider meetings happening with the White House at the same time that people were getting arrested outside. The campaign was able to bring together environmental groups, alongside farming groups (whose land was threatened by the pipeline), First-Nation communities, unions and other.

A number of speakers highlighted the importance of this, while recognising the challenges of holding it together, especially around the issue of the ‘jobs and growth’ agenda that is critical to many in light of the economic crisis . Weekly coordination meetings were held, but interestingly the campaign appears to have remained a ‘loose coalition’ as opposed to a tightly and more formally constituted one.

The 350.org folk have also written their reflections which are well worth a read.

The National Trust – the UKs most influential campaigning charity?

The Guardian had an interview with Dame Fiona Reynolds, the Director General of the National Trust on Saturday, where it asks if she is the most powerful woman in Britain at the moment based on the way that the organisation is currently campaigning against reforms to planning laws that threaten the countryside.

While, we don’t have a way of systematically ranking organisations based on influence, I think that the National Trust could make a genuine claim to be one of the most influential campaigning organisations in the country at the moment. Here’s why.

1. Membership – The National Trust announced earlier in the month that their paid membership is now over 4 million, that’s around 1 in every 10 voters. I’d suggest that many of these members are based in marginal constituencies around the country, as well as in safe Conservative areas, for example Surrey is the county with the most members. That means its members views are likely to be heard by lots of Tory MPs. Moreover, I’m sure that many MPs, Lords and other key influencers are also members, and share a natural affinity with the organisations aims.

Their reach is simply put enormous, with a membership far bigger than any single political party or trade union in the UK. Moreover, I suspect many members of the National Trust wouldn’t see themselves as the ‘campaigning types’ so the organisation has an opportunity to introduce campaigning to a whole new audience.

2. Influence – As Dame Reynolds says in her interview, the National Trust doesn’t want to be ‘became rentaquote, that wouldn’t be right. We reserve our voice for something that is really important, absolutely at the heart of our core purpose and touches what we stand for and where we make a difference’.

As such I’m sure when the National Trust chooses to campaign on an issue I’m sure it send panic through the heart of the government. They’ve proven they can mobilise hundreds of thousands of people to take action, most recently collecting 200,000 actions on a petition around the changes to planning legislation, and a look at the Guardian data on ministerial meetings suggest that the National Trust has met with ministers from across Whitehall.

But equally they’re smart about selecting issues that they campaign on, with Dame Reynolds saying they’d only work on issues that are ‘central to what we do and I suspect it would be rare, but when we make a contribution it matters’. Their influence meant that when they speak up those at the top of Government need to act, for example the Prime Minister recently writing to say ‘we should cherish and protect it [the countryside] for everyone’s benefit‘ in response to the Trusts most recent campaign.

3. Communications Reach – The organisations magazine has the 6th biggest magazine circulation in the UK, and is estimated to reach over 3.75 million people, which provides a great platform to inform and mobilise individuals to take action, imagine inserting a campaign postcard into every one that gets mailed. While their social media penetration is also impressive, the recent Charity Social 100 Index put them at number 7 and they have over 40,000 followers on twitter. All add up to a significant base from which they can mobilise.

Do you agree? What criteria would you use to identify the most ‘influential’ charity?

Astroturfing, 38 Degrees and MPs views of e-actions

Should we be concerned about Stephen Phillips MP writing to constituents in response to 38 Degrees last campaign to say that he will;

‘in the future not respond to campaigns run by what purports to be a, but what to is most evidently not, a non-political organisation’

Perhaps not, unless you work for 38 Degrees and even then I suspect that you’d think it’s good publicity. Although this tweet suggests that it’s not simply Philips who take this approach to 38 Degrees at the moment.

But Philips isn’t the first to complain, last summer we had another Conservative MP, Dominic Raab say;

‘there are hundreds of campaign groups like yours, and flooding MPs inboxes with pro-forma emails creates an undue administrative burden. I welcome anyone who feels strongly about AV writing to me in person – rather than copying an automated template’

While a few weeks ago Labour backbench, Steve Pound MP wrote in Tribune;

‘On any given day there will be between three and five campaigning bodies, trades unions or special interest groups encouraging their members and supporters to e-mail their MP – and woe betide the miserable Member who fails to reply by return’

It is of course easy to dismiss these MPs as a few grumpy MPs who simply need to get control of their inboxes, but are these the views of a growing majority?

If so, then I do think we need to worry as it could mean that e-actions to MP could rapidly become a blunt and ineffective campaign tool.

I’m not aware of any empirical evidence that exists about the views of MPs about e-actions, but anecdotally the MPs I’ve heard will tell you that they see e-actions as being less ‘influential’ as a handwritten letter, which itself is less ‘influential’ than a visit to a surgery (or similar).

I don’t think that this response of Philips means we should stop running e-actions to MPs, but I do wonder if as campaigners we need to work with the Speakers office and others within Parliament to help to identify a way of ensuring that those who take e-actions as a legitimate way of engaging in the democratic process aren’t ignored by MPs who simply think that these actions are a ‘nuisance’.

But it also highlights the importance of using other tools in our campaigning to demonstrate grassroots support, perhaps more interestingly is the description that Guido Fawkes used to describe 38 Degrees in his blog as a ‘left-wing astroturfing operation’.

Astroturfing being a term used in the US for a number of years to describe as ‘advocacy in support of a political, organizational, or corporate agenda, designed to give the appearance of a “grassroots” movement’.

It’s of course unfair and unfounded to because one of the other tactics that 38 Degrees selected to use to campaign on the NHS Bill was to encourage the public in Lib Dem constituencies to phone their MPs, and they’ve also spent months building local groups to get behind the campaign.

But the impression that some see many of the e-actions we’re generating as a sector are coming from organisations that don’t have any ‘grassroots’ support behind them is a concern, especially if the majority of MPs start to view them in this way.

Perhaps if there is a lesson to take from all of this, it’s that tending to and building a ‘grassroots’ is as important as building a big mailing list to generate e-actions.

Do you agree? How much longer do you think e-actions to MP will remain effective?

Evaluating Advocacy – Craft or Science?

“Advocacy requires an approach and a way of thinking about success, failure, progress, and best practices that is very different from the way we approach traditional philanthropic projects such as delivering services or modeling social innovations. It is more subtle and uncertain, less linear, and because it is fundamentally about politics, depends on the outcomes of fights in which good ideas and sound evidence don’t always prevail”

This is the central premise of a brilliant paper, The Elusive Craft of Evaluating Advocacy, by two academics from the US, Steven Teles and Mark Schmitt.

Although the primary audience of the document is grant giving foundations, the paper has some interesting reflections on the way that we look to evaluate our advocacy built around the concept that evaluating advocacy is perhaps more of a craft than a science.

The paper introduces 9 words or concepts that we might want to bring into our campaigning vocabulary when considering crafting our advocacy evaluations.

1. ‘abeyance’ – The value of keeping the fires burning on an issue even when little visible progress is being made. Critical given situations can often change quickly and without warning.

2. ‘strategic capacity’ – The idea that we should be less interested in evaluating a linear logic model, but instead look at the capacity of an organisation to read the external environment, understand the opposition and implementing the appropriate adaption.

Later in the paper, the authors suggest that ‘What really distinguishes one group from another, however, is what cannot be captured in a logic model—the nimbleness and creativity an organization will display when faced with unexpected moves by its rivals or the decaying effectiveness of its key tools’.

3. ‘spillover’ – a sense that campaigns can often operate devoid of consideration of other unrelated issues, but success elsewhere can often change the political opportunities for our campaigns if they fit a broader narrative set by a government.

4. ‘declining effacy’ – Over time some tactics grow old or ineffective, so organisations need to respond to this decline. The recognition that the ‘no campaign plan survives first contact with the enemy‘ means that campaigns need to continue to reassess and change their tactics.

5. ‘disruptive innovators’ – A strategy or organisational form that does not follow known strategies and the importance of not immediately dismissing new tactics that don’t work, but instead recognising that it can take time for innovators to find the most effective application.

6. ‘spread betting’ – In the paper this is the notion that funders should invest in a portfolio of opportunities, and that funders should have an organisational culture that can accept some failure, as long as they are balanced with notable successes. I’m sure the same principles should apply to organisations.

7. ‘policy durability’ – The need to see if a policy change actually sticks or creates a platform for further change. Build on the sense that advocacy requires long time horizons and doesn’t end when a piece of legislation is passed.

8 – ‘unit of analysis’ – A suggestion that rather than evaluating advocacy (that is the activities) the focus should be on a different unit of analysis, evaluating advocates, and their long-term adaptability, strategic capacity and influence.

9. ‘movement public goods’ – we should asses the value that organisations add to others, do they contribute to broader movement building efforts.

Learning from the 'Countdown to Copenhagen' campaign

Evaluation might be the last step in the advocacy cycle, but from my experience it’s often the one that we’re quickest to overlook, moving onto the next campaign as opposed to spending time reflecting on what’s happened.

It’s great to see Christian Aid make an evaluation of their ‘Countdown to Copenhagen’ campaign available online for others to learn from, as well as a management response to it.

It is an interesting (and short) read which gives an insight into the campaigning that the organisation did in the run up to the critical climate talks in December 2009.

It is an interesting (and short) read which gives an insight into the campaigning that the organisation did in the run up to the critical climate talks in December 2009.

It’s full of useful lessons for any campaign, and I hope it might encourage other agencies to make similar documents available. Here are the 5 things that I’m taking away;

1 – External moments need to be seen as commas in a campaign as opposed to full-stops. The evaluation makes a number of references for the need for the COP meeting in Copenhagen to be seen as a key moment in the ‘trajectory of the campaign‘ as opposed to the end of it. A good reminder that we can become too focused on an external moment and overlook the longer process of change that will be needed whatever the outcome of it.

2 – Involvement and participation of partners takes time. The report rightly recognises the way that the campaign looked to engage southern partners, saying ‘Christian Aid is clearly close to southern advocacy groups and networks and more ‘true’ to their approach and position than others‘ but also acknowledges the time that it can take to ensure effective participation from southern partners and allies which mean that time needs to be built-in to do this otherwise this engagement doesn’t become meaningful.

3 – Building in space for learning. It’s often the case in a busy campaign that it can be hard to feel that you have the space to think about what’s happening in the external environment. The evaluation suggests that time needs to be protected to ‘allow for reflection to take place‘ and ensuring the tools are in place to capture progress and achievement. A good reminder for anyone who hasn’t taken the time to review where their campaign is at recently.

4 – Know your core audience – The evaluation asks why the campaign ‘under-utilised church constituencies‘. I don’t know the reasons this decision was taken, but it seems to me this might have been a missed opportunity for an organisation that draws its support primarily from churchgoers. For me, it’s a reminder of being sure of the core audiences that your organisation can reach.

5 – Seeing the global – The report has lots of praise for the work that Christian Aid did with allies in EU recognising that ‘Countdown to Copenhagen was a unique advocacy initiative at the European level in terms of both the scale and sustained nature of joint working amongst Aprodev’ and encouraging a broader focus looking towards the US and others. A lesson in the rapidly changing nature of global decision-making and the need to be much more proactive at looking beyond the UK in the alliances we build.

What have you learnt from this evaluation? Have you seen other organisations make evaluations available online?

Be the first to know about new posts by subscribing to the site using the box on the right, adding http://thoughtfulcampaigner.org/ to your RSS feed or following me on twitter (@mrtombaker)