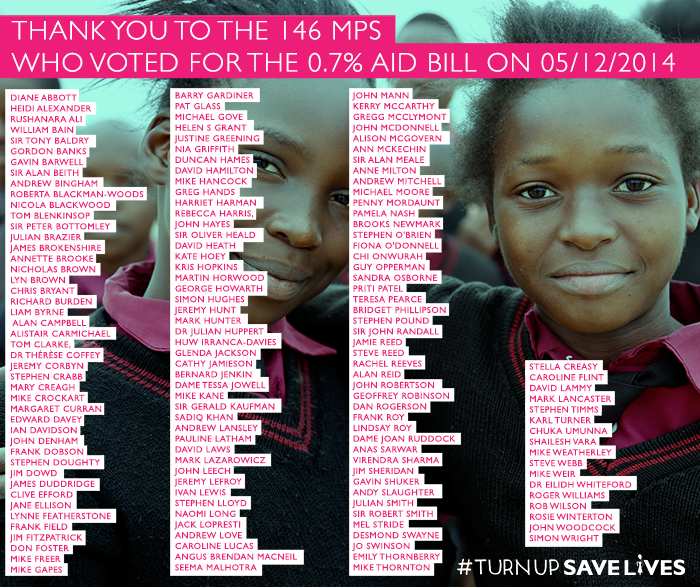

Yesterday, I was able to celebrate (with loads of others) a huge campaign victory.

Over the last few months, one of the campaigns that has kept me busy has been #TurnUpSaveLives, a push to enshrine in law our commitment as a country to spend 0.7% of our national income on international development.

It’s been hard work (with lots of spreadsheets), but I’ve been fortunate to work alongside a great team of colleagues from 20+ organisations.

The bill, which was brought to Parliament by a Private Members Bill from Lib Dem MP Michael Moore, has now passed through the House of Lords and should receive Royal Assent before the election. It’s a big win.

I’ve learnt a lot from the campaign, here are a few brief thoughts;

1. A week really is a long time in politics – Days before both the second and third reading, we were still short of the 100 MPs we need to commit to attend, as campaigners it felt like we were running out of time but turns out the MPs are used to making changes to the diaries at the last minute, so a week really is a long time in politics!

2. Movements take time to build – I really enjoyed reading this reflection from Steve Lewis from Results UK, a reminder that the ‘movement’ calling for 0.7% goes back over 30 years, and Steve’s personal memories of a lobby of Parliament in 1984 calling for 0.7%. The votes were the culmination of the campaigning that started over 30 years ago and had grown, often working on other related topics (debt, trade, tax) but coming back when needed to 0.7%.

3. Make sure you know the process – Private Members Bills (PMBs) aren’t like normal bills that are driven by the Government, so understanding the Parliamentary procedure was vital, for example PMBs require you to get at least 100 MPs to attend on a Friday (when most MPs are scheduled to be in their constituencies), have to pass a Money Resolution (where Parliament has to agree to spending money on what’s being proposed), and the outcome of the Second Reading is used to decide the composition of the Bill Committee.

It was vital to use supportive MPs to help us understand what to expect to make sure we didn’t miss an opportunity, as well as making use of the helpful Parliament website where you can track the progress of the Bill.

4. Opportunity Cost – For MPs to be in Parliament on a Friday, especially close to the election meant not attending a community event or meeting potential voters. We had to find ways to reduce the opportunity cost for MPs not being in their constituencies, for example we had a Lifesavers gallery where we publicly acknowledged (and thanked via twitter) who was attending, organised a photo moment with a celebrity to help MPs secure local media coverage, and placed a big emphasis on constituents writing or visiting MPs to ask them to attend.

5. Using Twitter – We got #turnupsavelives trending twice on the day of the Third Reading in December, it was thrilling, but looking through the tweets it proved that twitter can be a bit of an echo chamber, with most coming from those who were involved or supportive of the campaign.

However, where we did find twitter useful in the run up to to thank those MPs who had committed to attend or ask those who hadn’t to do so, as well as thanking those that did attend. Encouraging organisations to use their corporate accounts and also those of CEOs or other senior staff worked well, turns out MPs like to be thanked by NGOs. Having access to an in-house designer at Global Poverty Project to quickly turn around images we could share was invaluable.

6. Precedent – Often we’re campaigning were about looking to change somethings, but setting a precedent is one of the most overwhelming reasons not to do something for a politician. We found that early on in the campaign our hope to get parties to whip their MPs into attending was unlikely to happen, Labour doesn’t whip on Private Member’s Bill and didn’t want to set a precedent by doing so for this bill. So finding examples of where a party has done this before is really useful in demonstrating that you’re not asking to set a precedent in supporting your ask.

7 – Don’t forget to say thank you – I remember a MP once complaining to me that after he’d voted for something a campaigning organisation had asked him for the next letter he got was asking for something else. Its easy to forget to say ‘Thank You’ for MPs for voting (and we didn’t do enough after the second reading in September) but come the Third Reading, having a graphic ready to share the names of MPs who’d turned, sending cards from supporters, getting on the phone to key MPs, and writing letters from CEOs ensured we were doing all we could to show our appreciation to MPs who attended the vote.

8. Insider/Outside – The campaign was a great example of how insider and outsider tactics can work together. We needed to be mobilising constituents to email, tweet, call and visit MPs asking them to visit, that helped to create a belief that and a constituency of support, but we also needed to be working the corridors of Westminster, understanding the positions of the different parties, providing the arguments about why we need, getting CEOs to call key MPs to use their influence to make sure we reached enough MPs pledged to attend, etc.

9. Building the right coalition – We didn’t spend lots of agreeing how the coalition was going to work, instead we kept our structures lean and simple forming three groups (one for campaigners, media and public affairs colleagues) with central coordination from Bond. The Turn Up Save Live. We worked to ensure that we tried to get as many organisations involved, including Unions and Faith Leaders. On reflection, we could have done even more to build a unusual coalition in support.

10. Supporters loved it – Lots of organisations reported that the actions they’d invited supporters to take was one of the most popular actions, I think everyone enjoyed the binary nature of the campaign, that your MP was either going to turn up or not, rather than the indirect actions we’re often asking supporters to take appealed to people.

11. Working with Lords is completely different – That’s for another post, but we learnt quickly that the same approach wasn’t going to work. Lords need to be engaged in very different ways.

Want to learn more? I’d be delighted to come and speak to your team based on the learning from the campaign.

Category: evaluation

Can 'Theory of Change' transform our campaign planning?

To be honest, I’ve struggled to get my head around the ‘Theory of Change’ approach that I’ve seen being talked about across the sector over the last year.

I’ve felt that its something that could be an incredibly powerful tool, but found it’s been hard to really understand of it.

In an attempt to understand it, I attended a Breakfast Briefing organised by NCVO with Brian Lamb last month. Brian has been a leading proponent of the approach for use in campaigning and wrote this report which I blogged on last year.

Hearing Brian talk through how campaigners could make use of Theory of Change was really helpful at bring the theory behind the tool found in various reports and guide that I’ve read to life.

Hearing Brian talk through how campaigners could make use of Theory of Change was really helpful at bring the theory behind the tool found in various reports and guide that I’ve read to life.

I came away from the time enthusiastic about if for the following reasons;

1. It get’s us to question our assumptions – One of the central features of the approach is to get you to name and provide evidence for the assumptions you’re making that lead you decide that the impact a certain input will have

I’ve long thought that we need to more to justify the decisions that we’re making between impact and outcome, and Theory of Change actively encourages you to do this, demanding you to list your assumptions and discuss why you’ve made them.

In doing so, I think its likely to force us to ask the question, what are the ‘most effective approaches I could use’ as opposed to ‘what existing tools do I already have that I need to use’.

2. It builds from impact up – The first thing that the approach asks you to do is to decide on the impact of your advocacy, this is defined as ‘the ultimate effect on the lives of those you’re seeking change for’.

Brian suggested that while this might sound like a straight forward question to answer, it often takes groups considerable time to come up with the answer to the question, but in doing so they help to reach common understanding of the change they’re seeking.

I know I’ve been in campaign planning sessions before where we’ve spent the majority of our time on agreeing a strategy to reach a policy solution; as opposed to asking what impact we want to that solution to have.

3. Provides clear building blocks – The approach is simple and logical. Working upwards from impact, to mapping  the strategies that will be needed to achieve this, to looking at the outcomes needed from activities to achieve this, to looking at the activities that will be required at the heart of the campaign.

the strategies that will be needed to achieve this, to looking at the outcomes needed from activities to achieve this, to looking at the activities that will be required at the heart of the campaign.

Also, because the built, there are lots of existing tools that already exist that can be used to help to guide our theories of change. In the session, Brian shared the work of the Harvard Family Research Project which has undertaken extensive research to identify a number of common approaches to policy goals and activities/tactics. Great source materials to help in campaign planning.

4. Gives us a common language – At the heart of the Theory of Change approach is the need for dialogues and discussion to reach conclusions. In the use of approaches like ‘so that’ chains (where you need to articulate a logical path between the steps you’re suggesting).

Throughout the process it provides opportunities for campaigners to clearly articulate their approach, but also invite others to test and question the logic. I can see how this is really helpful in unpacking the ‘mystery’ of our campaign planning to others, and helping to answer the hard questions

5. Helps to think about the best ways of allocating resources – You’re required to put all the outcomes and activities on the table in the process, rather than selecting those you think possible with the resources that you have.

Doing that means you can look afresh at how you might resource new approaches, or think creatively about new alliances to forge. The research also has some invaluable ‘checklists’ about what an organisation needs to have the capability to undertake effective advocacy.

My conclusion. That its worth investing the time into grappling with Theory of Change because it’s got huge applicability to campaigning and that its great to find someone to help work you through an example of the approach in person.

Can these tools help to make campaign evaluation interesting?

Let’s be honest. Evaluating campaigning is a subject that excites few people, but it’s a really important part of the campaigning cycle.

Over the summer, I’ve been trying to think and learn more about campaigning evaluation, looking at the reports of other organisations that are available, like this one on Oxfam GB’s climate campaign, and learning about the favoured tools of funding institutions.

As you’d expect there are a wealth of approaches, but I wanted to share three tools that I found especially interesting;

Basic efficiently resource analysis – I came across this tool in the Oxfam evaluation where it was used to compare the perceived resourcing of activities to their impact on policies, political agendas or legislation. It seeks to identify the most efficient activities, in terms of achieving political impacts with the least resources.

It seems to be a really excellent way of engaging an organisation in a discussion about what works. As I understand it the report used it by surveying 200 individuals, both within and outside Oxfam who were involved/targeted by the campaign to share their opinions, so it was able to draw on the reflections of various groups. More on how the approach was developed for Oxfam here and here.

Bellwether methodology determines where an issue is positioned in the policy agenda queue, how lawmakers and other influential are thinking and talking about it, and how likely they are to act on it.

Developed by the Harvard Family Research Project, “bellwethers” are influential people in the public and private sectors whose positions require that they be politically informed and that they track a broad range of policy issues.

Bellwethers are knowledgeable and innovative thought leaders whose opinions about policy issues carry substantial weight and predictive value. The approach uses semi-structured interviews and the data helps to data indicate where an issue stands on the policy agenda and how effectively advocates have leveraged their access to increase an issue’s visibility and sense of urgency. More here.

The intense-period debrief is another tool developed by the Harvard. I thought that this tool would be especially useful, as so often in campaigning the evaluation gets left until everything is done and dusted.

The tool recognises that many advocacy efforts experience periods of high-intensity activity. While those times represent critical opportunities for data collection and learning, advocates have little time to pause for interviews or reflection. The unfortunate consequence is that the evaluation is left with significant gaps. Using focus groups or interviews its able to capture key information that might otherwise be lost in an end-of-campaign evaluation. More here.

For those interested in more on evaluation methods and approaches, BOND has produced this great list of tools that can be used. I’d also recommend this document from the Innovation Network on some more unique methods and this paper from the Harvard Family Research Project.

Reflections from campaigning in Brussels

Last week I spent a fantastic three days with campaigners from across Europe in Brussels calling on the MEPs and representatives of Member States to help to unearth the truth. We were calling on them to pass legislation that would require all oil, gas and mining companies registered in Europe to be open about the payments they pay for access to these valuable resources to governments.

It was the culmination of months of campaigning across Europe and we had a hugely productive time together, meeting with dozens of MEPs, handing over 10,000 actions to representatives of the Danish Government who currently hold the Presidency of the EU and holding a well-attended briefing in the Parliament.

I came back with lots of great memories and some reflections on campaigning towards the Brussels based institutions;

1 – Time – I was struck how much time many of the MEPs gave to the campaigners they were being lobbied by. Meetings of up to an hour happened on a number of occasions and it struck me that the pace of the debate is perhaps slower and more deliberative, coupled with the fact that MEPs are perhaps not as bombarded casework requests that they have time to invest into the issues that they’re interested in, which is predominately shown through their involvement in the different committees and groups.

I also got the impressions that although the political groupings were important they were far less controlling than in the Westminster system where the ‘whip’ is used to ensure MPs vote the right way and as such a space for discussion and agreements amongst those MEPs with similar political views as opposed to rigid voting blocs.

2 – Complexity – The European institutions are very confusing and eyes will often quickly glaze over when you start to explain the difference between the Council of Ministers and the Commission, but its worth investing the time in understanding how they’re meant to work and also the dynamics of how they actually work. I found reading this guide from BOND hugely useful. There are a huge number of opportunities for campaigners to utilise to push their issues.

3 – Importance – In the UK perhaps we’re guilty of disregard MEPs as having limited influence in comparison to MPs but the reality is that they have a significant amount of influence on certain issues. For example, if our campaigning is successful the legislation that we’re asking for will be implemented in all member states, achieving the same using a country by country would take much longer. On issues where the European Union has exclusive or shared competency we shouldn’t overlook the importance of engaging with Europe.

4- Absence – Many of the MEPs that we meet with remarked how much they valued hearing the views of civil society on this issue we were campaigning on as they’d already been lobbied by business groups. I heard one estimate that Brussels is home to 15,000 – 30,000 lobbyists, most of whom are employed by corporate interests, and that clearly presents a challenge for civil society which is likely to be unable to match that level of personal resource!

4- Absence – Many of the MEPs that we meet with remarked how much they valued hearing the views of civil society on this issue we were campaigning on as they’d already been lobbied by business groups. I heard one estimate that Brussels is home to 15,000 – 30,000 lobbyists, most of whom are employed by corporate interests, and that clearly presents a challenge for civil society which is likely to be unable to match that level of personal resource!

However, I didn’t get the sense that most MEPs have come under similar campaigning influence to their counterparts based in national capitals, as I walked around I saw lots of posters publishing the European Citizens Initiative (see my post on it here), which I sense is one way that the Commission hopes to engage citizen and civil society, but I also wonder if as organisation we need to be doing more. Perhaps it’s also time to create a pan-European equivalent of 38 Degrees focusing on activities in Brussels?

5 – Being European – Our campaigning was successful because we were able to build a partnership with colleagues from across Europe at the outset of our campaign, it meant that our supporters were lobbying in Brussels alongside campaigners from Portugal, Germany, France and the Netherlands, plus we were able to handover campaign actions from 22 member states. As UK campaigners I think we need to be doing more to help create these partnerships where they don’t exist.

6 – Using constituents to drive attendance. We were involved in hosting a very successful briefing event in the Parliament on Wednesday, with one civil society representative saying that the 15+ MEPs in attendance was unusual. I think this happened in part by asking our supporters to message their MEPs and invite them to come along to the meeting. It’s a tactic that I’ve seen used before in the UK and one that worked well in Brussels as well.

Have you been involved in campaigning in Brussels? If so, what insight would you share? If you haven’t, what are the barriers that stop you?

What did we really learn from Make Poverty History?

The Sheila McKechnie Foundation is running it’s annual People Power Conference tomorrow. It looks like a fascinating line up of speakers. Sadly I can’t make it in person although I’ll be doing my best to follow via twitter.

One of the sessions that stands out to me is the panel debate on ‘The Legacy of Make Poverty History‘, it was one of the first campaigns that I worked on professionally, so I’m interested in what the panel have to say about how we can still learn from the campaign.

One of the sessions that stands out to me is the panel debate on ‘The Legacy of Make Poverty History‘, it was one of the first campaigns that I worked on professionally, so I’m interested in what the panel have to say about how we can still learn from the campaign.

The Foundation have managed to organise an impressive line-up of speakers who were involved in the original campaign, including;

- Adrian Lovett, now European Director of ONE but working at Oxfam during 2005.

- Deborah Doane, Director of the World Development Movement, one of the organisations that was most outspoken about some of the tactics used in the campaign.

- Glen Tarman, Head of Advocacy at BOND, but working for the Trade Justice Movement during the campaign

- Kirsty McNeill, Founder of Themba Consultancy, formerly one of Gordon Brown’s speech writers and working at the Stop AIDS Campaign in 2005).

If I was able to attend here at the questions I’d be asking;

1. If we’d had the research and thinking done by the Common Cause team around the role of frames and values in campaigning available to use back in 2004 what might we have done differently?

2. Have we done enough to capture the learning from the campaign and share it with others across civil society? To my knowledge there has only been one significant academic study of the campaign by Nick Sireau. Do we need to be doing more to encourage academics to study our campaigns to help us increase our understanding of what works?

3. Make Poverty History was one of the first campaigns that effectively utilised email as a tool for action, building an email list of hundreds of thousands of individuals. How much should campaign movements like 38 Degrees and Avaaz thank Make Poverty History for demonstrating the effectiveness of this campaign target? How much impact did the e-mail actions actually have?

4. Tony Blair wrote in his memoirs that the campaign worked because ‘Bob, Bono and the NGO alliance had mounted an effective campaign…by demonstrating the breadth of public support for action on Africa. It was done cleverly, with them always giving enough praise to the leaders to encourage them’. I’d be interested in knowing if the panel agrees with the statement and if we need to do more to praise and encourage our targets?

Learning from Stop the Pipeline campaign

The Stop the Keystone pipeline campaign is one that may have passed many in the UK by but in the US its resulted in a huge victory for environmental campaigners.

In brief, the campaign was looking to halt the construction of a pipeline that would transport tar sands oil from Alberta, Canada across the Midwest of the US to the Gulf of Mexico. You can read more about the pipeline here, and a few weeks ago President Obama announced that he wasn’t approving the go ahead of the pipeline.

It’s a real success for the campaign despite the fact that the campaign believes it was outspent by approx. $60m to $1m by the oil companies behind the pipeline, and research has shown that spokespeople for the pipeline were much more likely to be featured in the media. Although those involved are keen to point out that the fight isn’t over.

One of the most striking tactics that the campaign used was a fortnight of action in Washington DC where over 1,000 people were arrested for taking part in illegal sit-ins. Watching some of the films from August are incredibly inspiring and moving but in many ways these actions were the culmination of over 2+ years of campaigning.

[youtube http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ozmOQqRw0j4]

On Thursday, I joined a ‘Debrief’ organised the New Organizing Institute which featured speakers from a number of the organisations that had been involved in the campaign. It was a thought-provoking session, and I came away reflecting on the following lessons learnt from the campaign.

1 – The importance trusted leaders – One of the speakers, spoke about the importance of bringing Bill McKibben into the campaign. McKibben is the founder of 350.org and was one of the first to write about climate change for a general audience over 20 years ago. The speaker suggested that his involvement changed the dynamic of the campaign, as he was perceived by many as a trusted leader who brought credibility to the urgency of the campaign message.

It’s a reminder that as well as friends and family who remain the best ‘messengers’ for any issue, some authority sources can be incredibly powerful at mobilising a group of individuals. Who are these in our movements?

2 – They called for a bold action – Bill McKibben is clear that the arrests outside the White House was a key tool in moving the campaign from a local one in the states effected to a national one. The called for a bold action, for activists to do something very real and something powerful.

Social media was used to mobilise people to attend the sit-ins in Washington. Many of those who got arrested had not done so before, and the photos and visuals helped to define the issue – make it a visually compelling action, while running the event over two weeks helped to create a political drama that draws out the story, providing an ongoing story that reporters could focus on.

Watching the films from the fortnight you get an incredible sense of a community amongst those involved in the campaign.

3 – Building locally and ahead of time – Although the peak of the campaigns activities appears to have been in August, listening to speakers from both the Energy Action Coalition and Sierra Club, it’s clear that important work that was done over many years to build campaigning activities in local communities.

In the case of the Energy Action Coalition starting on campuses during the Bush administration, knowing that their would be a day when a group of trained and mobilised young people would be needed. While for the Sierra Club it was going to communities in Nebraska and other effected states, talking to people, sharing stories and mobilising them as part of the campaign, long before the attention was focused on Washington DC.

4 – Using political donors and volunteers – The campaign realised that they couldn’t counter the influence of the significant financial donations that the energy industry makes to elected officials in the US, but they could mobilise the tens of thousands of individuals who had made small donation to, and in many cases worked for the Obama campaign in 2008.

Using this tactics they were able to demonstrate the level of concerns amongst a critical ‘base’ that the president needs to re-engage ahead of the 2012 elections. Meetings at regional offices of ‘Organizing for America’, the Presidents election organisation, as part of a Obama Check Up Day also helped to demonstrate this. Although, we don’t have a similar culture of politician donations in the UK, I can still see opportunities in approaching an issue in this way.

5 – Collaboration and coalition – This wasn’t simply an outsider campaign strategy, the coalition was an especially broad one, with insider meetings happening with the White House at the same time that people were getting arrested outside. The campaign was able to bring together environmental groups, alongside farming groups (whose land was threatened by the pipeline), First-Nation communities, unions and other.

A number of speakers highlighted the importance of this, while recognising the challenges of holding it together, especially around the issue of the ‘jobs and growth’ agenda that is critical to many in light of the economic crisis . Weekly coordination meetings were held, but interestingly the campaign appears to have remained a ‘loose coalition’ as opposed to a tightly and more formally constituted one.

The 350.org folk have also written their reflections which are well worth a read.

What makes a policy success? Lessons from inside government.

Most campaigns are looking to get government policies changed, but what can we learn from those working in government about what makes a policy success?

The Institute for Government has recently published a fantastic paper, which looks at what makes a ‘policy success’, drawing on insights from number of ‘policy reunions’ that were held with senior civil servants and government ministers involved in a range of ‘policy successes’ over the last 30 years.

These success including the introduction of the National Minimum Wage, to the Climate Change Act, and Privatisation in the 80s (I appreciate some readers wouldn’t see this as policy success!’).

The report defines a ‘policy success’ as “the most successful policies are ones which achieve or exceed their initial goals in such a way that they become embedded; able to survive a change of government; represent a starting point for subsequent policy development or remove the issue from the immediate policy agenda”.

Then sets out to identify some common factors which lie behind these successes, before providing detailed case studies for each of the issues. I’d recommend reading the paper for anyone who is interested in getting the perspective from the ‘other side of the fence’ about how ministers and civil servants perceive who successful policies come about.

For campaigners, I’ll concentrate on three of the factors that I think our noteworthy for our planning;

1 – Need for strong leadership. The paper suggests that in all of the cases they have benefited from a senior minister who has taken a personal interest in passing the legislation, in some cases staking their personal reputation on it coming about, but also having officials with credibility working on the issue.

In the case of climate change the paper cites the role that David Miliband played when he joined DEFRA and also the role of Sir David King, the Chief Scientist in highlighting that the issue was a bigger threat than terrorism.

For me this is a validation of the strategy that some campaigns use to make a particular minister a ‘champion’ for the topic, but also raise a note of caution of the difficultly of getting an issue on a ministers agenda if they’ve already decided what their priorities are going to be.

It also suggests that campaign can do more to make use of those posts within Whitehall, like the Chief Scientist, Chief Medical Officer, etc who are able to give independent advice from a position of authority within Whitehall.

2 – It takes time. Those involved in the discussions that helped to inform the paper are all quick to suggest that for most of the policy success the groundwork and ideas had taken significant amount of time to develop.

For example, the paper argues that much of the work that lead to the creation of the Low Pay Commission that brought in the minimum wage was done while the Labour Party was in opposition in the mid-90s, where some of the most contentious issues were raised and began to be addressed. This meant that when they won the 1997 election they were able to give extensive proposals to officials.

This lesson, coupled with the suggestion from some in the paper that the first year or so after an election are the critical window of opportunity, suggest that organisations that are looking to achieve policy change in the medium to long-term, perhaps because a proposal isn’t getting traction with the current government, would do well to engage in the ‘long game’ of opposition policy making.

3 – A robust evidence base – This factor is unlikely to come as a surprise to most campaigning organisations, whose campaigning is grounded in policy work, but the paper affirms the need for good evidence and analysis, but it also goes further by highlighting that the creation of an independent group/individual to look at the issue, like the Pension Commission or the Stern Report on Climate Change, were critical in providing the evidence that allowed governments to act on the issues, and providing a basis for the consensus necessary from all involved.

In the case of the Climate Change Act and the Ban on Smoking in Public Places, the paper has much to say about the important role that organisation like Friends of the Earth and Action on Smoking and Health (ASH) played in influencing the final outcome and providing ideas from outside government.

For learning from the ‘other side’ I’d strongly recommend a read of this report, as it provides some excellent challenges for the way in which we go about trying to get policies changed. If you read it, I’d welcome your comments and reflections.

Be first to know about new posts by subscribing to the site using the box on the right, adding http://thoughtfulcampaigner.org/ to your RSS feed or following me on twitter (@mrtombaker)

Working in coalition – learning from the last 10 years

A new report provide some important lessons about what works when it comes to campaigning in coalition.

Make Poverty History, The Treatment Action Campaign, Jubilee 2000, The Global Campaign for Climate Action (GCCA). All campaign coalitions that have been active in the last 10 years or so, but what lessons can we draw from them for current and future coalition campaigning?

With funding from the Gates Foundation, Brendan Cox has written ‘Campaigning for International Justice – Learning Lessons (1991 – 2001)’ which attempt to do this. It’s a really excellent read and is based on conversations with hundreds of NGO staff, politicians and civil servants to draw out key lessons from coalition campaigning over the last 20 years.

With funding from the Gates Foundation, Brendan Cox has written ‘Campaigning for International Justice – Learning Lessons (1991 – 2001)’ which attempt to do this. It’s a really excellent read and is based on conversations with hundreds of NGO staff, politicians and civil servants to draw out key lessons from coalition campaigning over the last 20 years.

The whole report is packed with useful reflections, some that you’ll agree with, others that you won’t, but as Cox quotes those who want to ‘repeat their successes must first learn from them’ so its worth reading.

For me, the most interesting section is ‘Identifying Themes’ where Cox tries to identify some core elements that have helped campaigns to succeed or fail. Here are the 10 or so that struck me the most.

1. Organisations are increasingly keen to demonstrate clear attribution of their impact, as such they become concerned that working in coalition can make it harder to attribute impact to one’s own organisation. This is pushing organisations to consider focusing on more and more niche areas where they can provide ‘impact’ but this overlooks the fact that the most important issues often need grand coalitions to achieve change.

2. INGOs are actually coalitions in themselves. That many of the largest organisations like Oxfam, Save the Children and Amnesty are made up of multiple national chapters and as such getting them to agree on a priority campaign can take a long time in itself, and as a result those INGOs are able to be as flexible as others would require them to be to help form effective coalitions.

3. Unusual coalitions still get noticed. The report cites the example of the Publish What You Pay (PWYP) campaign that got Shell on board which added more creadibility than the addition of many NGOs would have had. Cox also highlights the role that faith groups can have in helping to mobilise a more ‘mainstream’ public.

4. Coalition structures follow the ‘last worst experience’. Make Poverty History was set up without a high-profile secretariat to avoid the tensions that many had found in the Jubilee 2000 campaign that had one. Cox argues that the desire to avoid tension and compromise brand profile in a coaltition means that we’re forming a series of ‘lowest common denominator’ collaborations which are reducing their impact. We need to rethink our models of coaltition advocacy.

5. Trust matters. Cox points to the examples of the Treatment Action Campaign and PWYP which he describes as having ‘a close-knit group at the centre of thea campaign’ which meant high levels of trust. at the centre of the campaign. He contrasts this with the GCCA which started out with a small group, but over time saw that broken down as more staff came into the campaign and reduced its functionality.

6. The challenge of the ‘moment’. Cox highlights the challenge of a campaign focusing on a moment, a political opportunity where the campaign comes to a head, but argues that while they provide focus they can provide real challenges of keeping a campaigns momentum going beyond this.

7. Incrementalism can be a successful approach. Cox suggests that incrementalism in a campaign, the belief that a campaign should take a step-by-step approach to achieve its aims, is often the most successful approach. Suggesting that the evidence of the Internaitonal Camaign to Ban Landmines which successful focused on a targeted definition of landmines rather than going for a broader definition of cluster munitions, or the Jubilee 2000 campaign which focused on debt cancellation for specific countries rather than heading calls to focus on the cancellation of all debt.

8. The role for radicals. One of the main tensions in a coalition can be between those who want a incrementaal approach as opposed to a more radical approach. In practice this has often meant the formation of two coalitions but Cox suggests that utilising these differences can be helping to ‘shift the centre of gravity within a political space, and make the demands of the centerist group sound more resaonsable’.

9. Using celebrities. Another point of tension in many campaigns. Cox finds that those campaigns that have gone beyond a ‘photo call’ and invited celebrities to be involved in policy advocacy have often found that they’ve brought alot of strength to a campaign. He cites the use of George Clooney in the Save Darfur Coalition who has testified before Congress in the US as well as lend his ‘brand’ to the campaign.

10. Finding a common approach to evaluation. Their are lots of recommendations at the end of the report, but the one that caught my immagination the most, was a proposal to create a commonly reconised body responsible for high-quality evaluations which would help to improve future campaigns as well as providing reassurance to funders and supporters.

So what happens next? All in all a very useful report, but at the end of the report I’m left asking, what happens now? Brendon Cox makes many thoughtful recommendation and highlights some stark truths for the sector but my fear is that now the ink has dried on the report nothing else happens, especially as Cox has recently moved into a new role at Save the Children.

Evaluating Advocacy – Craft or Science?

“Advocacy requires an approach and a way of thinking about success, failure, progress, and best practices that is very different from the way we approach traditional philanthropic projects such as delivering services or modeling social innovations. It is more subtle and uncertain, less linear, and because it is fundamentally about politics, depends on the outcomes of fights in which good ideas and sound evidence don’t always prevail”

This is the central premise of a brilliant paper, The Elusive Craft of Evaluating Advocacy, by two academics from the US, Steven Teles and Mark Schmitt.

Although the primary audience of the document is grant giving foundations, the paper has some interesting reflections on the way that we look to evaluate our advocacy built around the concept that evaluating advocacy is perhaps more of a craft than a science.

The paper introduces 9 words or concepts that we might want to bring into our campaigning vocabulary when considering crafting our advocacy evaluations.

1. ‘abeyance’ – The value of keeping the fires burning on an issue even when little visible progress is being made. Critical given situations can often change quickly and without warning.

2. ‘strategic capacity’ – The idea that we should be less interested in evaluating a linear logic model, but instead look at the capacity of an organisation to read the external environment, understand the opposition and implementing the appropriate adaption.

Later in the paper, the authors suggest that ‘What really distinguishes one group from another, however, is what cannot be captured in a logic model—the nimbleness and creativity an organization will display when faced with unexpected moves by its rivals or the decaying effectiveness of its key tools’.

3. ‘spillover’ – a sense that campaigns can often operate devoid of consideration of other unrelated issues, but success elsewhere can often change the political opportunities for our campaigns if they fit a broader narrative set by a government.

4. ‘declining effacy’ – Over time some tactics grow old or ineffective, so organisations need to respond to this decline. The recognition that the ‘no campaign plan survives first contact with the enemy‘ means that campaigns need to continue to reassess and change their tactics.

5. ‘disruptive innovators’ – A strategy or organisational form that does not follow known strategies and the importance of not immediately dismissing new tactics that don’t work, but instead recognising that it can take time for innovators to find the most effective application.

6. ‘spread betting’ – In the paper this is the notion that funders should invest in a portfolio of opportunities, and that funders should have an organisational culture that can accept some failure, as long as they are balanced with notable successes. I’m sure the same principles should apply to organisations.

7. ‘policy durability’ – The need to see if a policy change actually sticks or creates a platform for further change. Build on the sense that advocacy requires long time horizons and doesn’t end when a piece of legislation is passed.

8 – ‘unit of analysis’ – A suggestion that rather than evaluating advocacy (that is the activities) the focus should be on a different unit of analysis, evaluating advocates, and their long-term adaptability, strategic capacity and influence.

9. ‘movement public goods’ – we should asses the value that organisations add to others, do they contribute to broader movement building efforts.