You might assume there isn’t much that campaign movements here in the UK can learn from an evangelical megachurch in the Midwest USA.

But academic Hahrie Han’s latest book, Undivided explores the experience of a group of church members who follow a racial justice programme as part of the churches activities, and it has a whole range of lessons for those of us looking at building people powered movements for change.

On a personal note, as someone who has grown up in and around churches since a young age, and at times has worked with colleagues and organisations who’ve been part of US evangelical community it was fascinating to have someone play back somethings that have always felt instinctive to how I’ve approached my organising.

I was reminded of this brilliant pamphlet Purpose Driven Campaigning, which draws on the lessons from the hugely influential Purpose Driven Church book which was all about how churches grow and applies those to movement building.

Some of us had some time with Hahrie when she was over the UK at the end of November for a book tour organised by the brilliant team at Act Build Change – and I took away the following reflections:

- We need to stop seeing people not wanting to get involved as the problem – they do, so it’s not a demand side issue, it’s a supply side one, and that’s on us. We need to be thinking about how we create replicable and attractive opportunities that people want to join.

Megachurches think a lot about the design of the experience that people have as they come into their spaces, and how they use small group to connect people into meaningful community. - Getting involved in public life is not a natural instinct – People are hungry to be in community, but they can find that in lots of other spaces well away from getting involved in change making. We should always remind ourselves of that when thinking about the design of the opportunities we offer.

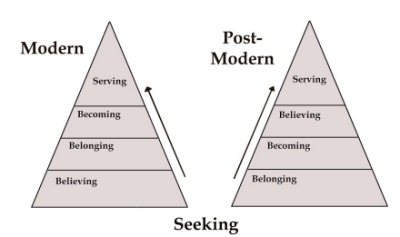

We need to supply meaningful ways people can get involved, and think deeply about the design of them given the competing demands. - Start with belonging before belief – the church that Hahrie studied didn’t expect people to believe in their creeds before they were able to belong – their logic is that finding belief comes from finding a place of belonging, and beyond that there will be issues/topics where people don’t agree, but they still find a community.

The book explores this around racial justice, but you could apply this to other issues where there was deep disagreement. Too often we put barriers in the communities that we create which prevent people from belonging unless they agree across a whole range of issues. That means our movements will always struggle to grow. - We need to develop asks that allow people to grow their own agency – many of the asks that we make as campaigners are ones that can be carried out in isolation, and are low risk for the people who take them, as there is little impact on them in terms of their time/money/effort if they don’t succeed. Actions like signing a petition reinforce to individuals that they are cogs in a machine.

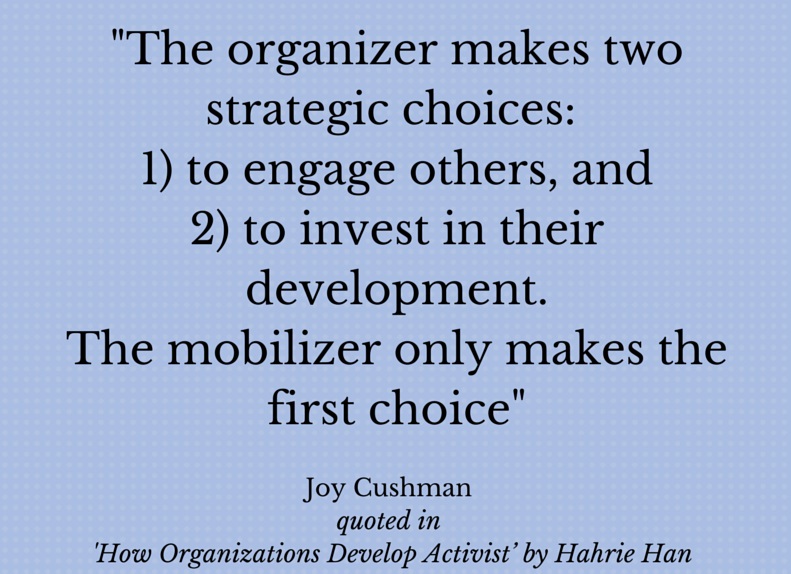

We can make a choice to develop an offer that need to be created in community, and higher risk for those that take them – i.e. they might put in lots of time/effort and the outcome does not get achieved. It’s in those asks that individuals grow as leaders, but also build community with others. - Invest in leaders – megachurches invest a huge amount in their volunteer leaders, inspired by the example of Jesus who spent much of his time teach/training his 12 disciples.

- Go to where people are – we are at risk of getting drawn into a context where there is a political class – who are driving the political system but amounts of a small % of the population, and a non-political class who are increasingly not speaking or understanding each other.

Megachurches have thought deeply about how they go to where people are – designing programmes and activities to reach all types of people – take a look here at the sheer range of groups available at the church Hahrie’s book is based.

- Remember what you measure is what matters – if you’re not measuring it and accountable for it, then you’re less likely to prioritise it.

More on the book here if you’re interested – it comes highly recommended.