The US Presidential election is less than 60 days away – and this post is (largely) a Trump-free zone.

As the most expensive campaign in the world, with over $1bn spent in the months leading to election day, it’s always an interesting place to spot campaign innovation, with each election bringing forward new ideas and approaches that often make their way into the wider campaigning landscape.

But this election will be different – with the spread of COVID-19 still high in the US, the campaigns have had to throw out their traditional playbook – out have gone the rallies, townhalls, and door-knocking that characterises a US election, and instead have come new approaches and tactics.

So with a few months to go here are a few things that I’ve spotted.

1. Relational organising – as candidates can’t doorknock, campaigns are putting lots of focus on relational organising, put simply, encouraging people to use their existing networks, their friends and family to vote for a particular candidate.

That might not sound like anything especially groundbreaking, but the difference in this campaign has been the availability of apps to support this directly so it will help you to identify those contacts that are most important and help people see how your friends respond – closing the feedback loop.

Apps and tools like Outvote, Tuesday Company and Outreach Circle are making it easier for individuals to do that (this from Kasch Wilder is a brilliant list of all the tools available), and at a time when candidates can’t get out and about to undertake the normal doorstep, this is about ‘recruiting and training trusted messengers’ who can be used to get messages to individuals who might not see (or might ignore) – early evidence shows it 3x more effective at getting people to vote than traditional ‘cold calling’ efforts of campaigns.

It’s an approach that could gain traction in the UK, and it’ll be interesting to see if some of the tools get adapted to be used in our political context.

2. User generated content – perhaps it’s a result of the times we’re in, but user-generated content has featured in many of the campaigns, for example here are Republicans Voters against Trump who’s whole approach is about getting short films of former Trump supporters, filmed on smartphones talking about why they’re not supporting Trump this time, or in Iowa, eventual caucus winner, Pete Buttigieg, used endorsements from supporters in every county to cut these films.

And, if you tuned in to any of the Democratic conventions last week you’d have seen plenty of content with high production values, showing that still has an important role to play, but it was split up with lots of clips from web cameras and smartphones. In the age of lockdown, we’ve come much more accustomed to watching content that is user-generated as well.

3. Branding – There are some fascinating reads from the 2016 campaign, about the thought that went into the logo and brands of Hilary Clinton, (and the critique that it reinforced the sense of being a centralised campaign, when her rival Bernie Sanders had a brand that was more open and adaptable), through to this on the Make America Great Again hat that, while ridicudled by many, was actually a piece of brilliant design.

This time around Hunter Schwarz at Yello has been doing an amazing job of chronicling the significance of the design approaches of the different campaigns – from the choice of color pallets to reflect the personalities of different candidates, to how campaigns are thinking about typefaces – it’s really fascinating.

I still love how Pete Butt has his own mood board on his website, but it matters because in an age where everyone can be a content creator, as a candidate you want to get your approach in the hands of as many as possible. It’ll be interesting to see how the Biden/Harris brand is reflected on at the end of the campaign.

4. Humour – if you’ve not stumbled across the Lincoln Project, you should look at their approach. It’s a well-funded group of Republican supporters who are able to produce slick and quick videos with the aim of challenging Trump’s narrative. Much of their strategy seems to be less about persuading wavering Republican voters to ditch Trump, but actively ridicule the President in the hope it’ll get a response.

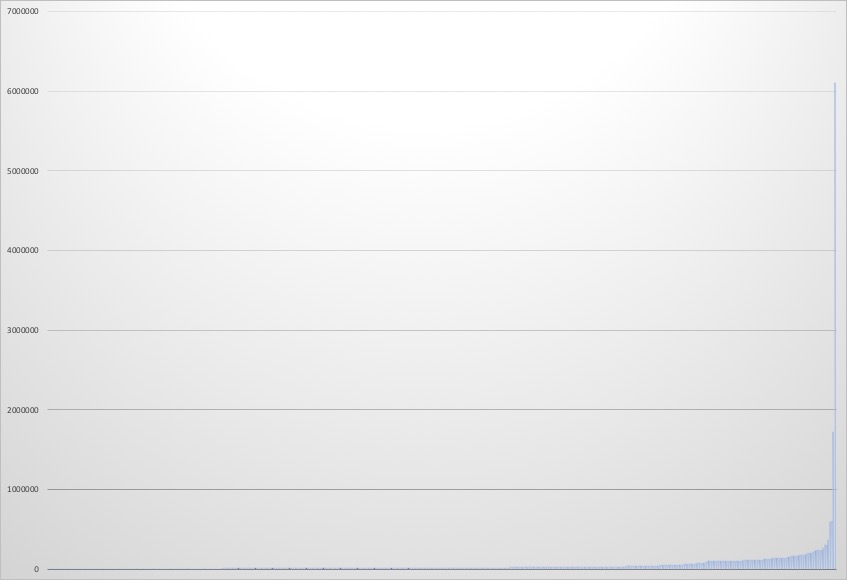

And it’s a strategy that’s working – their initial advert has a tiny ad spend, but crucially it was shown on Fox News at a time when Trump was on Twitter. Cue Trump tweeting about it, and millions more seeing the advert. This is an extreme example, but do campaigns spend enough time trying to cleverly provoke those they’re running against?

Similarly, this campaign cycle has seen social media influencers and content creators brought directly on board to campaign teams to produce memes and other content that will reach younger voters – for example, failed Democratic candidate, Michael Bloomberg was reported to have been paying millions for influencers to share about him back in the primaries, and the Lincoln Project has teamed up with the same group of content creators for the general election.

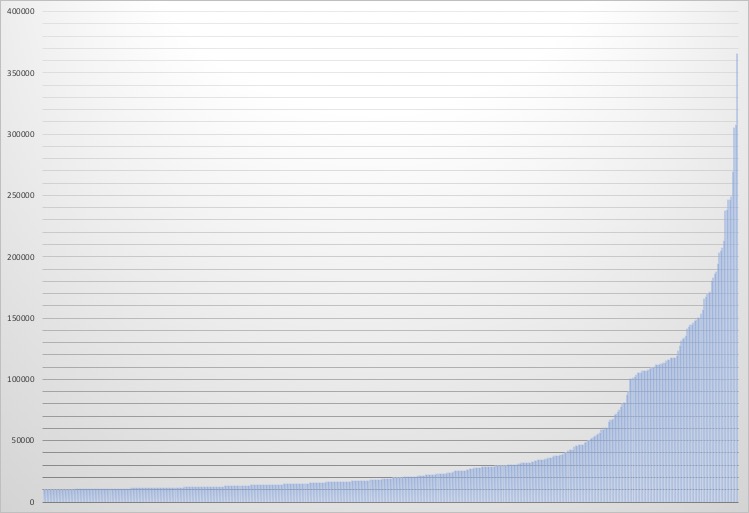

5. Winning takes years – I’ve been reading Upending American Politics – which explore citizen activism in the US from the Tea Party to the Anti-Trump Resistance, it’s an excellent collection of academic studies into why Trump won on over the last month – and the big takeaway for me is that he benefitted from a local Republican infrastructure in key states that had been deliberately built over years. It’s a theme that is echoed in this excellent piece by Pete Buttigieg Campaign Manager, Greta Carnes.

It’s easy to think that winning an election is about appearing a few months before polling day, but the evidence shows that the Republican Party has just been better at investing in and playing a long game. It’s a really good and important lesson for all campaigners (and those who manage campaign budgets) that results often don’t appear overnight, but are the product of smart, strategic and long-term investment towards a goal. It takes time and commitment to build to win.